Was it only a year ago when theaters around the country went dark, save for a lingering ghost light onstage? It feels more like 525,600 minutes, give or take a few—a period of ever-accumulating loss, with the odd glimmer of daylights and sunsets. I’ve been thinking about how we measure these elegiac anniversaries, in part because they line up with memories of loss in my own family. One of my beloved grandmothers, Yvie, died around this time two years ago; another, Linda, died this time last year—fortunately, in a way, after a full life, just before New York shut down.

In Jewish tradition, we observe the anniversary of a loved one’s death by saying the prayer of mourning, the Kaddish. The catch in socially distant COVID-19 times is that you’re not supposed to say the Kaddish alone. It’s a call-and-response prayer that requires a community to support you. In fact, it’s addressed to the community, rather than God, even as it extols the divine power to bring peace. A Jewish community—a minyan—requires at least 10 people to be present. How can we perform the rituals of mourning as a family, a congregation, a nation, when we still can’t gather safely in person?

Though rabbinic authorities have allowed remote workarounds for the Kaddish, I’ve taken heart from an extraordinary performance that reimagines the ritual, improbably titled A Kaddish for Bernie Madoff. It’s the story of its creator, Alicia Jo Rabins, a poet and musician who secured an artist’s residency on an empty floor of a Wall Street office building after the 2008 financial crash. She’d planned to work on a song cycle about biblical women called Girls in Trouble, but when she saw a picture of Madoff in the paper, she was transfixed: He looked like her dad. She became obsessed with the fraudulent investor and started to wonder what it meant that Madoff, so many of his victims, and she herself were all descendants of Eastern European Jews—how the sins of one member of a minority group seem to reflect on the whole. (“He’s pretty much the definition of ‘bad for the Jews,’” she says in the piece.) She heard rumors of a Florida congregation that said Kaddish for Madoff, as though he were dead to them.

Rabins turned out to be only a degree or two removed from Madoff. Her mother had a college roommate who’d evaluated Madoff’s credit; a friend knew a lawyer who represented some of his investors. Rabins interviewed her connections—a therapist whose parents had lost their savings, an FBI agent who had scoured Madoff’s office—and set their recollections to folk-rock cadences, composing a one-woman song cycle, playful and earnest in equal measure. (There’s nothing quite like seeing Rabins in a gray wig and pink pantsuit as Evelyn, the credit-risk analyst, singing “Due diligence!” amid a flurry of flower petals.) The show builds toward her own startling, transcendent version of the Kaddish, along with a surprising recognition of the way we’re all a little Madoffian in our quest for returns without loss, “a world without failure, a line that goes up and up.”

Rabins premiered Kaddish at Joe’s Pub, in New York City, back in 2012, then developed and toured it around the country for a few years, and now it’s been made into a film, directed by Alicia J. Rose. (The two Alicias, both based in Portland, Oregon, met after one received an email intended for the other.) The film, which will be available online in April at the Ashland Independent Film Festival, is part docudrama, part first-person narrative, part Jewish-feminist fantasy. Rose, who has a background directing music videos, surrounds Rabins with unexpected imagery: As Rabins explains Kabbalistic teachings about human interconnectedness, a chorus of synchronized swimmers paddles around her in the shape of a mandala that swirls, somehow, into an office coffee maker. If Anna Deavere Smith, Sarah Koenig, and Joey Soloway wrote a self-reflexive musical about finance and religion, it might approach the film’s impish, mystical spirit.

In Angels in America, one of Rabins’s touchstones for an artwork in which ancient traditions illuminate everyday life, a secular Jew—the playwright Tony Kushner’s stand-in, Louis—is summoned to say Kaddish for Roy Cohn, the demonic prosecutor. Louis can’t remember the words—he confuses the Kaddish with the Kiddush, the prayer over wine—until the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg, one of Cohn’s victims, magically appears to prompt him. (After the final v’imru, amen, she adds, “You son of a bitch.”) My grandma Yvie refused to see Angels because of this scene; as a lifelong lefty who once joined a picket line outside her own father’s kosher delicatessen, she thought Kushner was reviving a McCarthyite scourge to mock a Communist martyr. She might have had a case in an earlier scene, when Cohn tricks Rosenberg into singing him a Yiddish lullaby, “Tumbalalaika,” which my grandma and my mother used to sing to me. But the Kaddish isn’t ultimately a prayer for the dead; it’s a reminder to the living to affirm unfathomable grandeur in the world and strive for peace on Earth. Rosenberg is really blessing Louis. “You did fine,” a nurse says when Louis finishes the Kaddish. “Fine?” he answers. “That was fucking miraculous!”

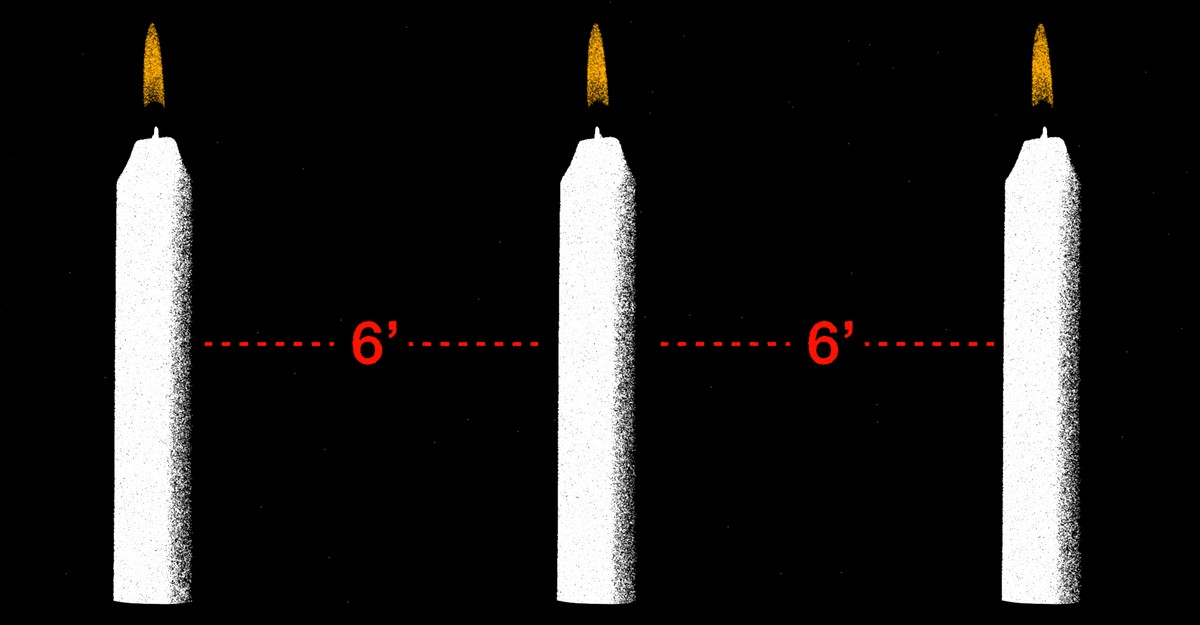

A sense of the miraculous infuses Rabins’s Kaddish as well. When she notices that Madoff has “kind eyes,” a picture of him tacked to her office wall quivers into hand-drawn life. Those eyes flicker and blink back at her. As Rabins’s investigation concludes, a Buddhist monk—who also happens to be Jewish—tells her that Madoff represented the fantasy that we can control life’s inevitable losses. “The only transcendence is fully embracing the ups and downs,” Rabins chants, over a plaintive violin. (Though she was classically trained as a violinist, Rabins also toured with a klezmer-punk band.) At the end of the film, she summons a minyan of fellow artists, each holding a candle, to witness her Kaddish for Madoff. Although the prayer is usually spoken, she starts to sing its Aramaic text, alternating major and minor thirds—life’s ups and downs. Then, with an electronic pedal, she loops her voice, adding a new harmonic layer with each line. (If you made it to the end of Pitch Perfect 3, you saw Anna Kendrick perform this technique.) It’s a ritual of mourning that accrues beauty as it recurs—a technical illusion that, as Kushner advised in his staging notes for Angels, lets the wires show.

Watching this Kaddish on-screen, I felt an acute sense of loss: for the shared presence that the film captures, for live performance in a physical space, for artists’ livelihoods, for Madoff’s victims, for COVID-19’s death toll, for my Jewish immigrant forebears. But the resonant harmonies also gave me hope. Works of art can help us heal and transform from afar. Though my grandma’s Judaism was more of the lox-and-bagel variety, I think she would have relished Rabins’s Kabbalistic approach. She also believed that we are all connected, and that we have an obligation to care for one another, especially the elderly, in the face of an economic system that rewards individual gain. Her pension, after a career as a special-education teacher, allowed her to take me to see Fiddler on the Roof twice on Broadway; had her savings been invested with Madoff, as several pension funds were, they might have vanished. At the end of her life, when she could hardly recognize anyone or put together a sentence, I would sing her tunes from the musicals we’d seen together. When I started “If I Were a Rich Man,” she squeezed my hand and murmured back, “Biddy biddy bum.”

Strictly speaking, I’m not expected to say Kaddish for my grandma, because her own children—my dear mother and aunt—are still alive. And yet I’ve said the prayer, over Zoom, my unmuted voice out of sync with those of the other members of my Reconstructionist congregation. As we wait for the vaccines to kick in, the economy to revive, and the arts to come back, I feel the need to imagine other rituals of connection too. With a wig, a violin, and an electronic pedal, Rabins offers a way. She wrote to me that she doesn’t feel a difference between performance and ritual, song and ceremony: “I believe it’s all one practice of facilitating healing—catharsis, transformation, whatever we want to call it.” I’ve been listening to her rendition of the Kaddish over and over, singing along with its circling harmonies, feeling a sense of release, letting the pain of loss go, and yet being called to repair it, to refashion the broken pieces of the world into something sustaining. It’s a blessing.