The wolf’s yellow eyes, sharp claws, and snapping teeth haunt our fairy tales and idioms, Erica Berry writes in her recent book, Wolfish. She asks why the animal has persisted as such a potent symbol of fear, arguing that this may color the way we see the world we share with animals and one another. By deconstructing stories such as “The Three Little Pigs” and “Little Red Riding Hood,” Lily Meyer wrote this week, Berry asks what dangers these canine villains are standing in for.

Berry is far from the only writer to investigate the significance of well-known fables. In Beauty and the Beast, Maria Tatar collects fairy tales revolving around a millennia-old trope (a human marrying an animal) and shows how they are “an expression of anxiety about marriage and relationships—about the animalistic nature of sex, and the fundamental strangeness of men and women to each other,” Sophie Gilbert explains. These accounts indicate what preoccupied our ancestors and what morals they hoped to impart. The impulse to communicate values through storytelling has remained strong across time: A century ago, British socialists tried to disseminate their ideology by reworking folk tales, a strategy we might recognize in contemporary titles like Chelsea Clinton’s children’s book She Persisted, J. C. Pan writes.

Fables often crop up in unexpected places. Sarah Chihaya writes that Yiyun Li’s The Book of Goose “is ostensibly a realist historical novel about the lives of women and girls in mid-century France ... [but] secretly dwells in the realm of fairy tale.” Li shows us why we’re so drawn to these kinds of stories. As Chihaya argues: “We are all, whether we realize it or not, constantly engaged in the process of mythmaking in an attempt to understand the inexplicable.” But this simple logic isn’t always sound. Adoption, for example, is often portrayed as a magical ending whereby a family is finally complete. But in Somewhere Sisters, Erika Hayasaki dispels this idea. Placement with a different family frequently creates feelings of pain and dislocation; insisting that adoption must mean living happily ever after can compound that hurt. Unwinding the narratives of our culture isn’t a fanciful pursuit: It makes space for new meanings and new ways to live.

Every Friday in the Books Briefing, we thread together Atlantic stories on books that share similar ideas. Know other book lovers who might like this guide? Forward them this email.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What We’re Reading

Amanda Shaffer

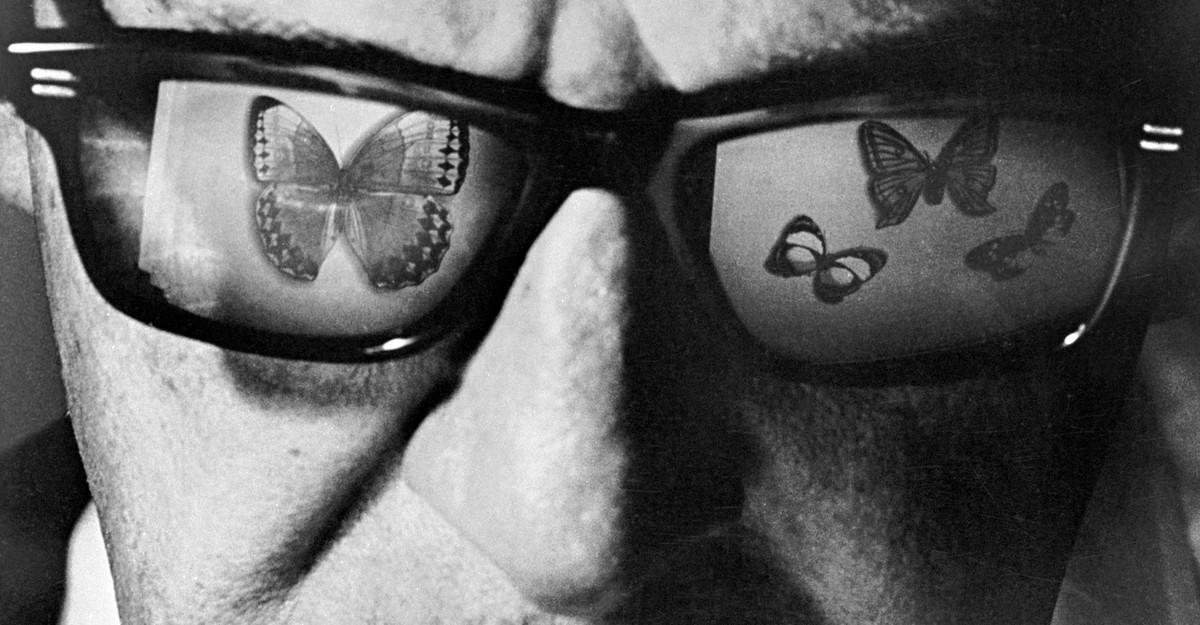

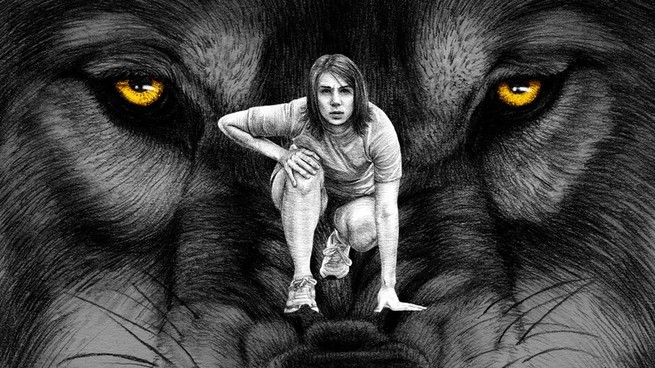

The book that teaches us to live with our fears

“Berry writes evocatively about these real wolves, yet she seems consistently drawn away from the wolves themselves and toward humans’ responses to them. Her writing is richest when she fully commits to examining wolf metaphors and the ways in which we turn even very real wolves into symbols.”

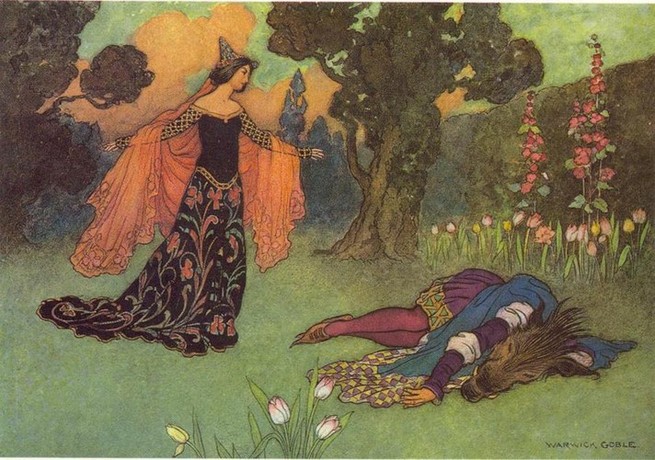

Warwick Goble

The dark morality of fairy-tale animal brides

“As Maria Tatar points out in the superb introduction to her new collection Beauty and the Beast: Classic Tales About Animal Brides and Grooms From Around the World, the story of Beauty and the Beast was meant for girls who would likely have their marriages arranged. Beauty is traded by her impoverished father for safety and material wealth, and sent to live with a terrifying stranger. De Beaumont’s story emphasizes the nobility in Beauty’s act of self-sacrifice, while bracing readers, Tatar explains, ‘for an alliance that required effacing their own desires and submitting to the will of a monster.’”

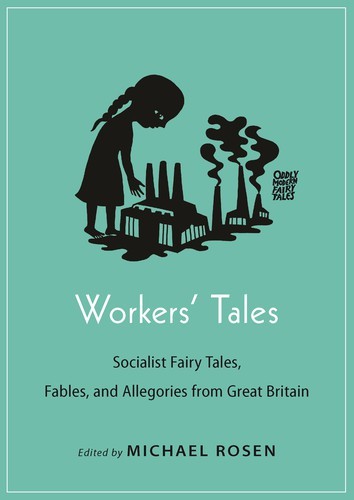

Princeton University Press

Fairy tales for young socialists

“But if attempts to steer children toward politics through literature feel somewhat of-the-moment, they aren’t new: More than 100 years ago, British socialists undertook a similar, if decidedly more militant, project. A new book, Workers’ Tales: Socialist Fairy Tales, Fables, and Allegories From Great Britain, exhumes several dozen fables and stories that first appeared in late-19th- and early-20th-century socialist magazines.”

Getty; The Atlantic

A novel with a secret at its center

“Li depicts Fabienne as almost superhuman in both marvelous and terrible ways. As a character, she gives Li a chance to explore the strange power of the myths we form about the people who shape us. Yet what really lies in Agnès’s own heart, and the novel’s, is only dimly revealed and much harder to bring to light. To do so is the real work—and pleasure—of reading this subtle and evasive book.”

Getty / The Atlantic

Adoption is not a fairy-tale ending

“Fairy tales about adoption don’t circulate just among the public; they can be internalized by adoptees ... In her interviews with adoptees, [the sociologist Indigo] Willing noticed that when holes in their narrative about why they were orphaned could not be supplemented with facts, the adoptees turned to fantasy-like tales and speculation passed on from parents. Those she interviewed for her master’s thesis repeated “rags to riches” tropes.”

About us: This week’s newsletter is written by Emma Sarappo. The book she just finished is My Men, by Victoria Kielland.

Comments, questions, typos? Reply to this email to reach the Books Briefing team.

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.