This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

“Masking has widely been seen as one of the best COVID precautions that people can take,” my colleague Yasmin Tayag wrote this week in The Atlantic. But a new review paper suggests that population-level masking might offer far less COVID protection than was previously thought—and, as Yasmin points out, the findings are already fueling Americans’ mask wars. I called her to find out more.

First, here are three new stories from The Atlantic:

A New Turn

Isabel Fattal: What do you make of this new review?

Yasmin Tayag: First of all, it’s done by Cochrane, a really well-regarded institution. So there are not that many concerns about this being a dubiously designed study. What it tells us is that the research on population-level masking suggests that that doesn’t really work. This means that mask mandates, or requiring an entire population to wear a mask, don’t do much to actually stop the spread of disease. This is different from individual-level masking, which we know a lot more about. If I wear a mask or if you wear a mask, we know that it’s still likely to be protective.

Isabel: You write in the piece that “the pandemic has presented many opportunities for the U.S. to gather stronger data on the effects of population-level masking, but those studies have not happened.” Why not?

Yasmin: There haven’t been a lot of those studies in the U.S. or worldwide. Part of the reason is that they’re difficult to set up because they require huge groups of people and are expensive. And they’re hard to do in practice, because to really look at whether wearing a mask can stop the spread of the coronavirus in a group, you would have to make sure that everybody in that group wears their mask properly all the time. But people are bad at wearing masks. It’s so hard to control for every single moment. Any instance in which someone might slip and take their mask off for a minute is a chance to confound the results. They might get the virus in that moment.

Isabel: Why is it so easy for Americans to fight over masking?

Yasmin: Unfortunately, masking has become so tied up with people’s political identity: Either you’re pro-mask or anti-mask. I personally have always been pro-mask, and so it can feel really unmooring to see a study like this done by a reputable group showing that what we believed to be true about masking may not actually be true. I think people at this point are unwilling to take in new information because it’s tough to change your mind yet again, or to grapple with new information yet again. And we’re tired of thinking about it.

Isabel: You write in your article that the best time to learn more about masking is before we’re asked to do it again. What does this mean for future pandemics?

Yasmin: The Science desk at The Atlantic is very on top of the bird flu right now, which is showing some troubling signs of being able to jump to humans. If it does, we as a society will have to figure out, again, What are our mitigation strategies? Because bird flu is also a respiratory virus, like the coronavirus, masking would seem like an obvious choice. But now we don’t know whether telling everybody to mask makes sense. And if we don’t know that for sure, then enforcing a policy like that could just risk raising everyone’s ire again, for maybe not a good-enough reason.

Isabel: Right. And if public-health officials do recommend something that turns out not to be necessary, then they lose some of their capital to get people to do other things they may need to do.

Yasmin: Totally. Where we want to be is in a place where we can confidently enforce a public-health policy and know that it works, and be able to show the evidence that it works, so that there’s less public squabbling over it.

Related:

Today’s News

- President Joe Biden made his first extended public remarks on the objects that the U.S. shot down over North American airspace this month, emphasizing that the U.S. is not seeking conflict with China.

- A Georgia court released part of a grand-jury report from its inquiry into potential 2020 election interference by Donald Trump and his allies, which recommends the indictment of “one or more” unnamed witnesses.

- The Infowars founder Alex Jones has been “holding firearms” for January 6 rioters, a new bankruptcy filing shows.

Dispatches

- Work in Progress: Derek Thompson probes the “national crisis” of rising teen anxiety.

Explore all of our newsletters here.

Evening Read

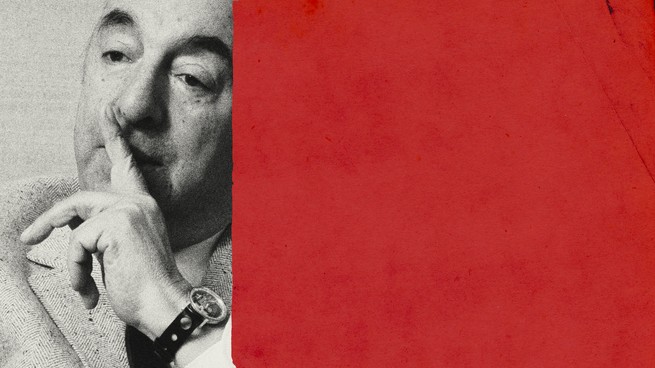

Who Poisoned Pablo Neruda?

By Ariel Dorfman

Repressive regimes tend to be unimaginative. They persecute and censor their opponents, herd them into concentration camps, torture and execute them in ways that rarely vary from country to country, era to era. As the outrages pile up, public opinion becomes exhausted.

Once in a while, however, a story surfaces that is so startling, so malicious, so unheard of, that people are jolted out of their fatigue.

Recent news about the mysterious 1973 death of Pablo Neruda, the Chilean Nobel Prize winner and one of the greatest poets of the 20th century, has created such an occasion. According to Neruda’s family, a new forensics report conducted by a group of international experts has concluded that he was poisoned while already gravely ill—a victim, most probably, of the Chilean military he had politically opposed. Even the most jaded onlookers should feel disturbed enough to pay attention—not just for what this development reveals if it is in fact true, but for how it might shape the legacy of one of history’s most complicated and most talented poets. Neruda’s own reputation is already blemished, his considerable moral failings as a person having overshadowed the once-universal acclaim for his art.

More From The Atlantic

Culture Break

Read. Revisit Wuthering Heights, the “bold, brutal masterpiece” by Emily Brontë, ahead of a new film about the author’s life that hits theaters tomorrow.

Listen. Indulge your analog-media nostalgia with this Atlantic Spotify playlist, a tribute to “the enduring romance of mixtapes.”

P.S.

When I asked Yasmin what book, show, or movie she’s been enjoying lately, she mentioned Vagina Obscura by Rachel Gross. “It’s like a voyage into the very poorly understood history of the female reproductive system. It is so illuminating and also such an adventure,” she said. As she was talking, I realized that her fellow Science writer Katherine J. Wu made the same suggestion in the Daily last summer (unbeknownst to Yasmin). So consider the book doubly endorsed by our writers.

— Isabel

Did someone forward you this email? Sign up here.

Kelli María Korducki contributed to this newsletter.