When Judy Blume began writing books about young people decades ago, the category of “young-adult books” didn’t exist. But she didn’t shy away from controversial topics—periods, sex, race, religion—in her stories about “kids on the cusp” of teenhood and adulthood. Instead, her work spoke to the realities of adolescence that some adults avoid, so much so that fans sent Blume letters about their own lives. She forever changed what a coming-of-age novel could be, Amy Weiss-Meyer demonstrates in her profile of Blume. In the years since the publication of such staples as Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret and Forever ..., books about adolescents have continued to push boundaries, and their commitment to reality is insightful for both juvenile readers seeking to find their place in the world and older ones reflecting on growing up.

As an adult, the writer Shauna Miller read Stone Butch Blues by Leslie Feinberg when she fell in love with a butch woman. The book follows Jess, who finds her place in the lesbian community of Buffalo, New York, after dropping out of high school, and her exploration of gender and sexuality in the years that follow. For Miller, Jess’s story demonstrated that butch masculinity can be soft, even romantic, in ways she didn’t realize as a teenager. Ajo Kawir, the teenage protagonist of Eka Kurniawan’s Vengeance Is Mine, All Others Pay Cash, also struggles with his nascent urges: He is unable to get an erection after witnessing a traumatic event, which alienates him from other boys his age. These almost-men deal with their overflowing emotions, both positive and negative, through fighting. Kurniawan’s novel provides nuance to what might just look, from the outside, like useless performances of aggression.

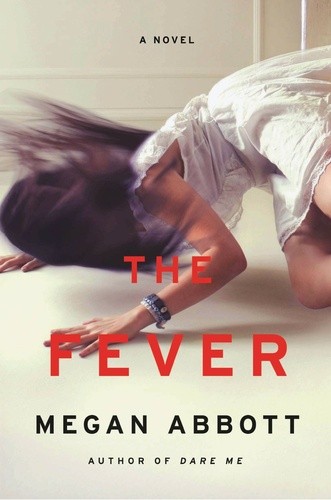

And, in perhaps a bit of the spirit of Judy Blume, many contemporary coming-of-age novels highlight the experiences of young women and the fraught dynamics of teenage girlhood. The group of girls at the center of The Lucky Ones by Julianne Pachico contend first with “epic” birthday parties and then, over time, with the lasting consequences of war and tense class dynamics in Colombia. In The Fever, the author Megan Abbott explores the reverberations of a mass hysteria, harkening back to the madness of the Salem witch trials with the added complexity of a suburban-high-school environment and the pacing of her previous noir fiction. Even when youthful characters are figuring things out, even when they do not yet feel like adults, or do not feel whole, their stories can still prompt older audiences to wonder about their own identities, and recall the futures they imagined for themselves when they were on the cusp.

Every Friday in the Books Briefing, we thread together Atlantic stories on books that share similar ideas. Know other book lovers who might like this guide? Forward them this email.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What We’re Reading

Erika Larsen for The Atlantic

“Today’s 12-year-olds have the entire internet at their disposal; they hardly need novels to learn about puberty and sex. But kids are still kids, trying to figure out who they are and what they believe in. They’re getting bullied, breaking up, making best friends. They are looking around, as kids always have, for adults who get it.”

???? Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret, by Judy Blume

???? Letters to Judy: What Your Kids Wish They Could Tell You, by Judy Blume

Leslie Feinberg

The importance of Leslie Feinberg

“Jess’s identity is so much more than her appearance. It’s more than her choice to work in a male-dominated factory world. It’s more than those simple and severely punished offenses against both womanhood and manhood. It’s more than the fistfights with other butches as a desperate attempt at intimacy, more than disappointing her great love, Theresa, with her emotional and intimate distance. By the end of this book, butch identity comes from letting love’s light trickle through a crack in the armor.”

Beawiharta / Reuters

Eka Kurniawan’s darkly comic tale of boyhood

“Vengeance isn’t trying to show the fights’ beauty for beauty’s sake, but to illustrate how a boy might find them beautiful—freeing, wild, their own form of political identity and coalesced power, a way to not have control and be okay with that.”

???? Beauty Is a Wound, by Eka Kurniawan

???? Man Tiger, by Eka Kurniawan

Ajay Verma / Reuters

The Lucky Ones is no ordinary coming-of-age novel

“‘Lucky’ is a relative term. Growing up, whether the girls like it or not, means coming into uneasy proximity with a conflict that wears on, claiming family and friends and teachers. The vocabulary of war becomes the vocabulary of everyday life—and vice versa.”

Little, Brown and Company

Writing of rage and the teenage girl

“Abbott threads The Fever with fear: that first loves are ephemeral, that friendships are frail, that the integrity of family and community are questionable at best. She is perhaps best known for her early period noir fiction, and here draws upon the hardboiled tradition in style and pacing, starting multiple fires throughout the novel—a mysterious ritual, sexual awakenings, parental strife, internecine high school social quarrels—each to be dealt with in turn.”

???? The End of Everything, by Megan Abbott

???? Dare Me, by Megan Abbott

About us: This week’s newsletter is written by Elise Hannum. The book she’s reading next is Piranesi, by Susanna Clarke.

Comments, questions, typos? Reply to this email to reach the Books Briefing team.

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.