The other night the gin bottle slipped off the sloping top of the csimbalom which we use for a swishy kind of bar in the living room, and I got thinking about how people come to the house and invariably ask to see the csimbalom. They take the hammers and whack away, trying to get a melody out of an instrument strung by the Devil so that it would be Hungarian, and different, and hard to play anything on but those mournful gypsy airs.

We have a csimbalom because my father once lent Uncle Arthur two hundred dollars and in payment Uncle Arthur finally sent us the csimbalom, which he said was worth much more since it was played at the St. Louis World’s Fair and by no less than Kukuricza János to accompany Rigo, the great gypsy fiddler who came over especially to play at the Café Royal. I had been taken to the Café Royal in New York as a child, to see where Theodore Roosevelt had sat while Rigo played in his ear, so I was impressed by the gift from Uncle Arthur. My father wished he had the two hundred dollars — and what the hell good was a csimbalom that nobody could play but a gypsy? The csimbalom stood in the family house, and when we divided up, I took the csimbalom because of sentiment.

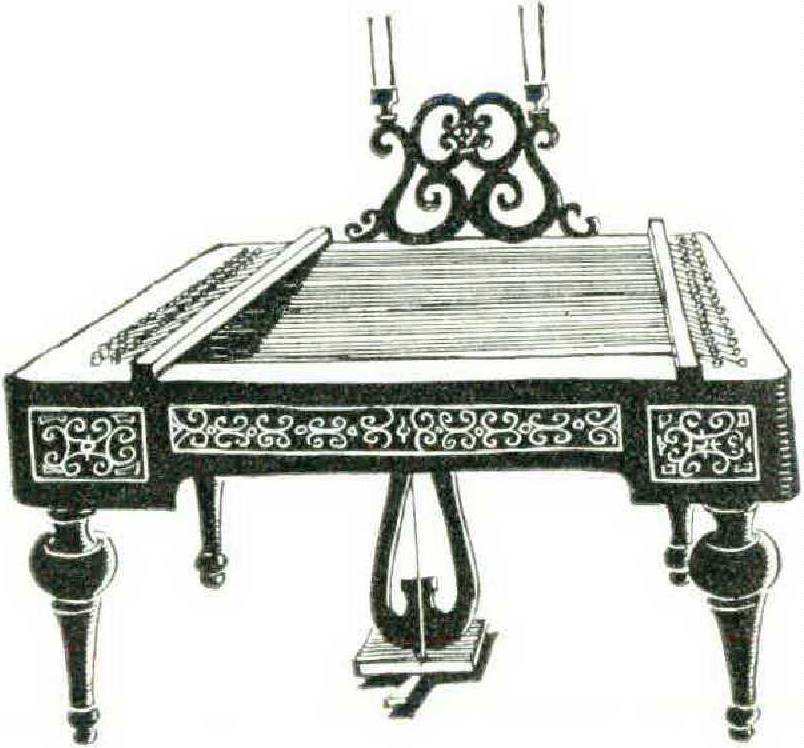

My wife thinks everything useful should be used, and the csimbalom is one of her minor irritations. It is lovely and black and has one of those curlicue black music stands with candleholders which Mozart could have used. Now it is only a kind of regal useless piece; the top slopes, and the glasses slide, and the bottle falls off often.

Once we went to hear the Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy conducting, play the “Hary János” Suite by Kodály. This is about the only orchestral piece worthy of the csimbalom; in fact, it has a section devoted to gypsy tunes which can’t be played on anything else. For the occasion there was a Hungarian sitting with the orchestra, playing solo on the orchestra’s csimbalom. As soon as the man had struck the first chord. Betty said, “Go back and ask him to come right over after the concert and play our csimbalom.”

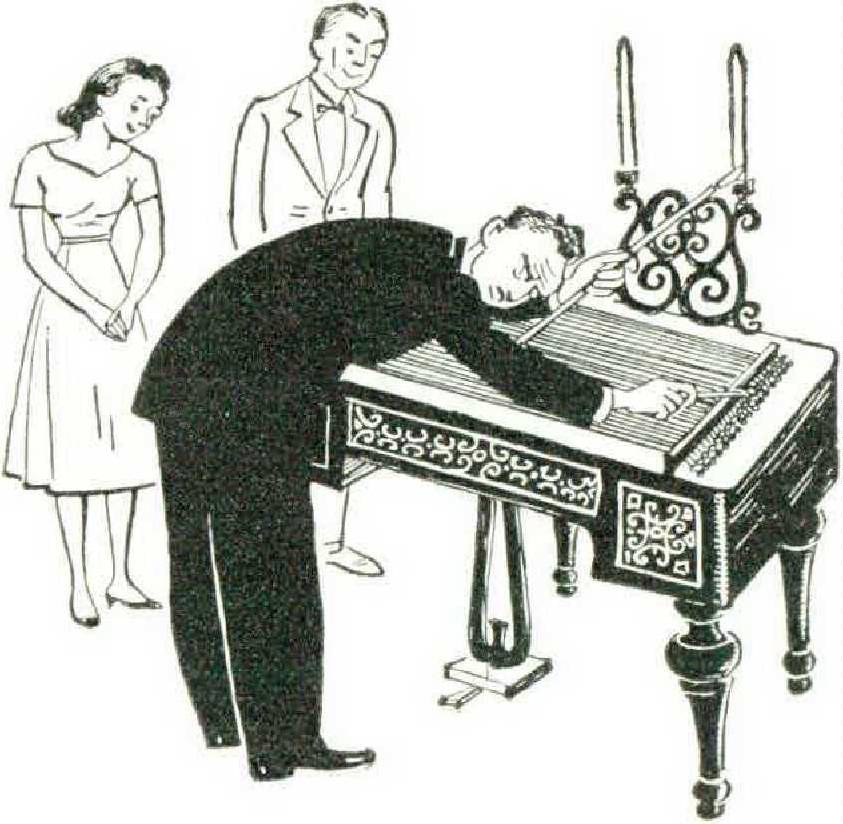

I dutifully went back and asked the gentleman. Boy! he sure was a Hungarian. He would come if I could assure him that the instrument was in tune, warm, and a csimbalom worthy of his great talents. I assured him. The man was worn out. The orchestra’s instrument had been lying cold in the basement all through the war, and he had spent a day and part of the early evening banging away and warming it, but he said he would come.

Betty was radiant. We invited a couple to come back; we gave the soloist a good warm meal and be sat down and played. The instrument had been repaired a few months before by a member of the Society of Ancient Instruments and I thought it was in fine shape. I say the soloist played. I mean he played a few notes, stopped, tightened a couple of strings, played a few more notes, and stopped again. This went on for as long as patience lasted, and then the musician said it was impossible to play without a violinist accompanying and also a bass, since the instrument is scored as a background to other instruments and does not sound right as a solo. Well, it was pretty late at night to go out and find a gypsy fiddler and a bass player, so we just had a couple of drinks and closed the box, and I thought that playing csimbalom records would satisfy Betty.

A couple of nights later, Betty said, “I think we should have a big party and get a gypsy to play our csimbalom for all our friends. You can get one if you just try.”

Before I could turn over, I knew I was a goner. “Look,” I said, “did I ever tell you what my father told me about gypsy musicians? They drink everything. A gypsy band visited his village, and they came to the inn and sat down and unslung their csimbalom and started the fiddles going, and asked for a bottle of palinka. This is a brandy made out of plums and is a quick blow to normal people, but the more the fiddlers played the more palinka went down, until even the bar was out of plum brandy; whereupon the chief fiddler went behind the bar, took down a bottle, had a swig, and then handed the bottle to the bass player, who also took a swig, and to the csimbalom player, who turned his face away after he had his swig. The bottle was a bottle of carbolic acid which the bartender kept for killing rats.

“I never found out whether the gypsies kept on playing, but my father also told me that gypsies steal everything movable, and there is a statue in the Royal Palace in Budapest of a gypsy stealing which was a favorite of the Emperor Franz Joseph. I saw the statue when I was in Budapest. What I mean is, if I happen to find a gypsy csimbalom player, I will be worried the whole time about my liquor, the silver, and maybe even violating you or the cook. That is the low esteem in which I was raised to hold gypsies, and if you want a csimbalom player, I have now acquainted you with the facts.”

Betty said, “That may have been true in Sátoraljaújhely, where your parents came from, but we are in America, where gypsies only tell fortunes and steal big estates from batty old ladies and drive highpowered motor cars. Besides, maybe a csimbalom player does not necessarily have to be a gypsy, but only a poor Hungarian who earns a living in a steel mill and pines his heart out at night playing csimbalom in a Hunky combo and thinking of drinking palinkas in good old Sátoraljaújhely instead of Coca-Cola in Phoenixville. Now look,” said she, “don’t put your back up. Just make believe that we are engaged and are in New York and you are telling me about Tante Jennie and Kukuricza János. You would find a gypsy joint soon enough if you wanted to cry over a bottle, and there must be a csimbalom player where there are two Hungarians.”

“Well,” I said, “New York is a cosmopolitan city, but where, oh where, can I find anything as civilized in this town?” We started and I said, “Let us go and find out if Gondy’s restaurant still lives.” Gundy’s restaurant was a little one. He had catered to all the Hungarians and served a meal which was hard to get down, what with prohibition and only needled beer. The place had about five tables which were covered with soup-stained cloths, and the proprietor always served his family, his guests, and everybody else from the family kitchen.

As soon as my father entered, Gondy would curl his long black mustachio and yell for his wife, who would come out of the kitchen drying her hands on her apron. She would shake hands all around and greet us all by our first names and tell us what was good. There would be a heavy chicken soup with the fat floating on the top, and then stuffed cabbage, boiled chicken, boiled beef, chicken paprikash, pigs’ knuckles, and other heavyweights. This would be followed by dobos torte, strudel, palatchinka with lekvar, noodles with almonds, and six cups of coffee. Gondy would pass around a box of cigars and we would roll home and sleep.

But those days had passed and I went back like a prodigal looking for a csimbalom player. Gondy was dead but the place was run by Csillag, who boasted that he was FBI. We had dinner and it was overfilling and wonderful. As we plied the toothpicks, which are a sign that the dinner was a success, I said. “Csillag, where can I get csimbalom player?”

“A csimbalom player?” said Csillag. “Budapest or maybe New York. I remember Feri Sarkosi, he used to play csimbalom maybe forty years ago at the L’Aiglon.”

“Listen, Csillag,” I said, “all right, all right. I remember Feri Sarkosi and even Kocze Antal, but what I want is right here and now a live csimbalom player.”

“Look, Mr. Bendiner and Mrs. Bendiner, I remember your father and mother —may they rest in Heaven, they were real Hungarians. Your father wrote a policy on me when I was only a waiter for Gondy and the other day it ran out and I sent my kid to college. He would want a csimbalom player maybe for a wedding or a funeral or even maybe only to get drunk and cry, but please, Mr. Bendiner, what do you want a csimbalom player for?”

I said, “I want a csimbalom player because I got a csimbalom and my wife, who is not Hungarian, hates to have a csimbalom around without having it played.”

“You got a csimbalom?” said Csiliag. “First, is it in tune? And second, is it a good enough instrument for a gypsy to play, because the csimbalom requires more than just anybody should play on it?”

“Listen, Csillag,” I said, “my csimbalom was played on by Kukuricza János, and I guess if it was good enough for Kukuricza János it is good enough for some puddler you got around here. Do you or do you not know a csimbalom player?”

Csillag thought for a moment and said, “Go to the Hungarian Club on Girard Avenue and ask the boy who sets up the pins if his father still plays bass with Ferencz Kecske who works at the factory.”

We went to the Hungarian Club. Il was too early for the players to have slept off their supper and be ready for beer and bowling, but the pin boy was there. He said his father did play bass for Ferenc/. Kecske and please go to the saloon at the angle of Orianna Street and if his father was not sitting having a beer the bartender would direct us. We went to the saloon and nobody else was there, but the bartender directed us to a house up the street.

Mr. Kecske was about to go to bed but he pulled on his pants, buttoning while opening the door, and asked who sent us. We told him Csillag and his son, and he said he would get dressed and come to the saloon and talk to us. We waited and had a drink. I told him that I wanted a csimbalom player and nobody else. “That is impossible,” said he. “First, a csimbalom cannot be played alone — it must have a bass and a violin. I am bass. Fedaksari János is violin, and Csendes Nagymihaly is csimbalom.”

“Listen,” I said, “listen. I simply want a csimbalom player to play for my guests. We have a csimbalom; we want somebody to play it; we don’t want any bass and we do not want a violin — just a csimbalom player.”

“Wait,” said Mr. Kecske. “Sit here, have a beer, wait five minutes.

I will produce.”

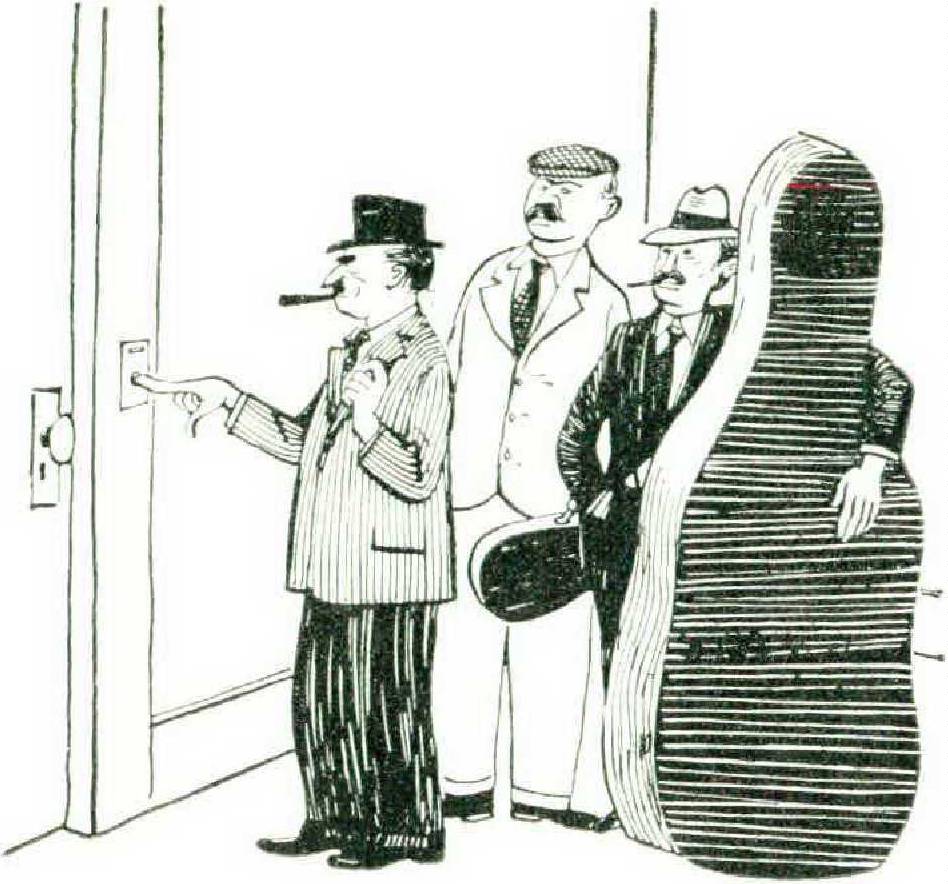

We had a beer, we had a couple of beers; it was getting late and I wanted to go home. Finally the doors opened and in came Mr. Ferencz Kecske bearing a bull fiddle, and Mr. Fedaksari János carrying a fiddle case; Csendes Nagymihaly wheeled in a csimbalom from the back barroom. They unbuttoned their instruments, took a slow beer, and played — without doubt, the lousiest gypsy trio combination I ever heard. I looked at Betty and said, “you see.”

The trio stopped and came over. I said, “I will take the csimbalom player for one night, supper and drinks; come on Saturday night at seven and ready to play.”

Csendes Nagymihaly drew himself up to his full four feet and said, “I do not play without my bass and violin; and besides, I must first come and see if the instrument is in tune and fit to play.”

“Listen,”I said, “come alone or not at all. You can look on Friday and play on Saturday.”

On Friday the three showed up and the csimbalom player warmed the instrument, played a few chords, tuned, pulled at the strings, played a few notes, bowed, and they played a piece. “O.K., boys,” I said, passing the bottle, “I still take csimbalom.” I warned Betty that he was probably insulted and might not show up at all.

On Saturday we put away all the extra silver and locked the liquor closet and put a private bottle alongside the instrument. Mr. Nagymihaly arrived alone, promptly at seven, smelling of pomade. He was dressed in a dinner jacket and had in his upper pocket a silk handkerchief which he used too much, spraying the room with cheap perfume. The guests arrived, and made noises about the queer instrument and asked Csendes how it worked, and spilled drinks into it while examining the strings.

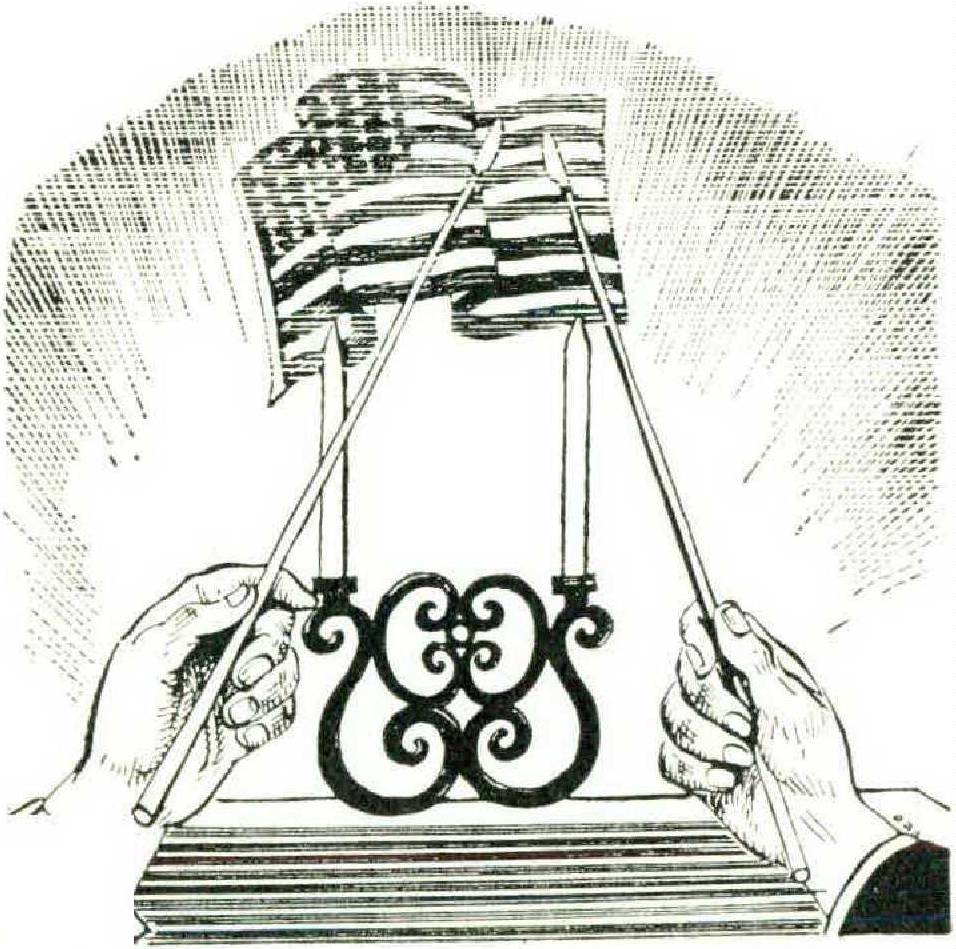

Finally, with a low bow, Mr. Csendes Nagymihaly sat down, pushed his hair back, picked up his hammers, and went into a noisy rendition of Sousa’s Stars and Stripes Forever. It was off beat and he must have learned it from a Hungarian record, but the guests were too polite or tight to notice and they applauded; so he encored with The Blue Danube. He bowed and I pulled him into the dining room and said, “Listen, what goes on here? I hired you to play Hungarian music. How about Csak Egy his Lenny or En Vagyok a Falu Rosza or Boszi Ne Sirjon?”

Mr. Csendes Nagymihaly drew himself up and said arrogantly, “That’s old peasant stuff. My combo doesn’t play Hungarian gypsy music. That’s for the old-time csárdás crowd. We play all the Hungarian clubs — Scranton. South Bethlehem, Easton, Allentown, Phoenixville, and weddings and Bar Mitzvahs in New York, but no gypsy stuff. That’s old hat. Either I play American or go home.”

Months later we had a funeral in the family and Uncle Arthur came. He gave one look at the csimbalom and burst into tears. This is an old Hungarian sentiment and might have meant that he was glad to see his old instrument, or it reminded him of an old girl in Sátoraljaújhely, or he figured he got gypped on that two-hundred-dollar debt, or he was just plain showing off. Anyway, Betty gave him a Kleenex, we took off the lid, and Uncle Arthur sat down and picked up the hammers.

He tossed back his hair and said, “I remember when I was living in Paris the great Claude Debussy was my most intimate friend, and one Sunday when I went to his house, there he was with a big sheet of paper stretched out on the table, and he had two penholders in his hands and he was playing the penholders across the paper on the table as if he were trying to play an instrument, and I said to him, ‘Debussy, what are you doing?’

“ ‘Well,’ said Debussy, ‘last night I heard a gypsy orchestra and I am trying to remember how that csimbalom was strung.’ ”

Uncle Arthur said, “I took the penholder and sat down and drew out for the great Claude Debussy the whole scale system, which, being Hungarian, is of course different from all other systems. And I will draw it out for you, Betty.”We got a big sheet of paper and he ruled it all out and marked out the whole scale.

“Now,” said Betty, “do me one favor. I have waited long years for somebody to play that csimbalom. Will you please play just one little tune?”

“Play!” said Uncle Arthur. “It is impossible, my dear child. You do not understand — you cannot play solo on a csimbalom, you must also have a fiddle and a bass.”