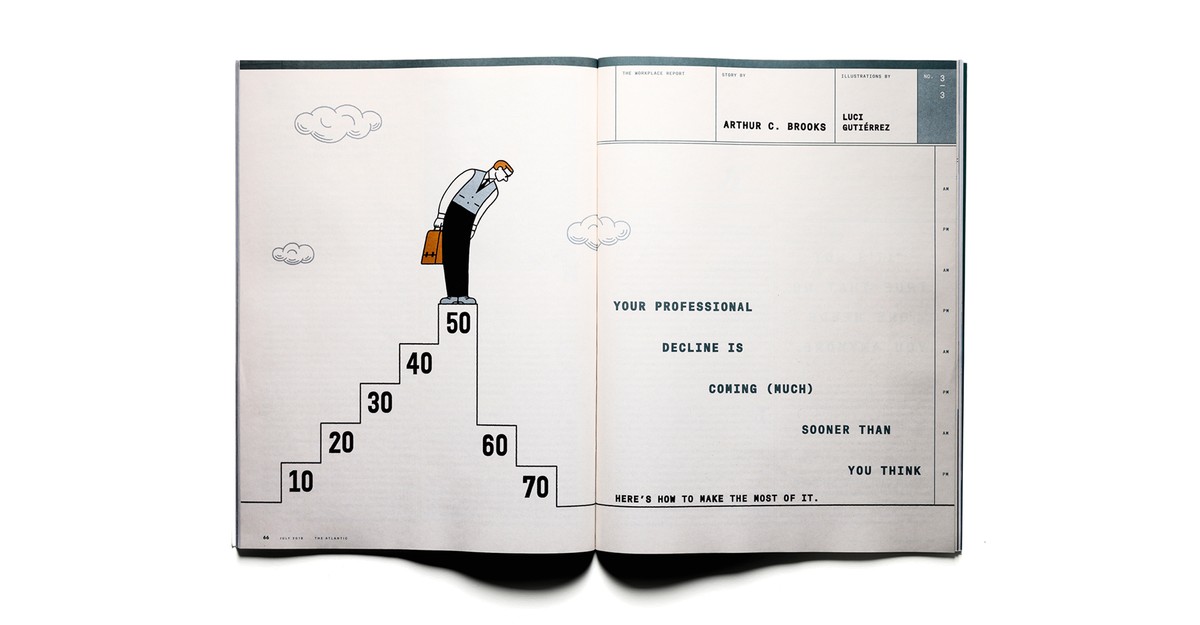

Your Professional Decline Is Coming (Much) Sooner Than You Think

In July, Arthur C. Brooks wrote about how to make the most of it.

Arthur C. Brooks’s insightful piece really hit home for me. I was a primary-care physician for 33 years before closing my office to concentrate on elder and end-of-life care five years ago, when I turned 65. I had started feeling my fluid intelligence ebb, even as I was treating an ever more demanding caseload in a setting of corporatized health care.

My solution was to turn my practice over to a capable younger physician and embrace long-term-care geriatrics, where I have time to indulge my patients and lead from my heart.

I work with an excellent hospice team and facility staff. Not a week goes by when I don’t hold the hand of a dying person or sign a death certificate. My goal is to bring my patients the comfort and peace that allow heartfelt communication and that is only possible with reconciliation. Like the Buddha Mr. Brooks encountered, I have contemplated death and no longer find it threatening.

John Jefferys Bandola, M.D.

Kingston, R.I.

The article by Arthur Brooks is magnificent. As an 85-year-old professional, I have already experienced the world of angst he is now entering. Take his advice, please. He is especially right about the desire to explore spirituality, which professionals tend to neglect in their early years.

W. R. Klemm

Bryan, Texas

I seem to have intuited and followed most of Arthur Brooks’s precepts. During my quite successful academic career, I gradually shifted from research to teaching, and from graduate to undergraduate teaching. I retired at 66. Ten years later, I keep my hand in research, but purely for my own intellectual pleasure, and to keep my brain active and healthy. I don’t even have an office at the university; I work at home in my pajamas.

The only item of Brooks’s advice I disagree with is Sannyasa, the “focus on more transcendentally important things.” The material world is wonderful, and I now get to enjoy it in ways I never could before. I will not “leave my office horizontally,” but I may be taken horizontally off a cruise ship.

A demigod of my vocation, John Maynard Keynes, is supposed to have expressed only one regret toward the end of his life: “I did not drink more champagne.” This seems a worthy goal for all economists, indeed for high achievers in all careers, and much more enjoyable than Sannyasa.

Avinash Dixit

Princeton, N.J.

I am an 85-year-old male who retired at “the top of my game” at age 62. The retirement decision was based on family considerations: Our married daughter, a soon-to-be mother, lived in Portland, Oregon, and asked that my wife and I move to her town. The first six months of settling into our new home kept me occupied, so I did not feel an identity crisis. But soon I began to wonder whether we had retired too soon, and to feel a bit lost and depressed.

My wife suggested that I return to playing the clarinet. It did not take me long to realize that having the time to rehone my playing skills was a gift. I got engaged in Portland’s music community, and eventually became principal clarinetist in two orchestras. My greatest compliments come from other, often younger musicians who attend my recitals and consistently tell me that I continue to improve.

Jules Elias

Portland, Ore.

Arthur Brooks omits an important point about professional decline after age 50. For skill-based professions, waning creativity is outweighed by increasing experience and judgment. Chesley Sullenberger was 58 when he landed a jet on the Hudson River. For heart surgeons like me, the 50s are generally peak years.

Moreover, it is baffling that Brooks picked Darwin as an example of someone who “stagnated” after age 50. Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859 at age 50, but he published The Descent of Man in 1871, books on reproduction in plants in 1876 and 1877, and his final book in 1881, the year before his death, at 73. By then, deteriorating health had confined him to his house and garden, so he wrote about earthworms.

A better example of declining creativity would have been Albert Einstein. His “miracle year” came in 1905, at age 26, and he published his theory of general relativity in 1915, at 36. Nothing thereafter came close, and his lifelong ambition, a unified field theory, escaped him.

Lawrence I. Bonchek, M.D.

Lancaster, Pa.

Arthur Brooks writes almost entirely of the experience of men (and of men of a certain era, socioeconomic class, and race). Although a reader might be able to infer something of the experience of women in his article, he effectively ignores them.

So what of the women whose careers have moved forward in fits and starts, due to time spent parenting or the need to counter legal, cultural, societal, or institutional restrictions? What of the women who never had the chance at a career, if indeed they wanted one? Do they feel the same sensations of decline? To what stage do they now move?

Shana Judge

Albuquerque, N.M.

The Worst Patients in the World

Americans are hypochondriacs, yet we skip our checkups. We demand drugs we don’t need, and fail to take the ones we do. No wonder the U.S. leads the world in health spending, David H. Freedman wrote in July.

I found this article to be a refreshing departure from most writing about health care. Of course culture matters. As a medical anthropologist, however, I thought David H. Freedman missed a key factor in health outcomes. Many people who have the worst compliance rates and outcomes (Freedman lists smokers, diabetics, and people with sedentary lifestyles as examples) also have the same socioeconomic status. In other words, they’re broke or too busy to do everything they’re supposed to.

While I agree that more attention needs to be paid to how American culture affects our health-care choices, I’d hate to see money and social class fall out of the analysis. These factors also affect how people perceive their doctors. I grew up in farm country and my family—who often couldn’t afford all the recommended treatments or travel the two hours it would take to see specialists—viewed hospitals and clinics with suspicion. Local cultures and medical institutions affect and shape each other. Both have to change for Americans to have any chance at a better health-care system.

Theresa MacPhail

Brooklyn, N.Y.

We can all acknowledge that a sedentary lifestyle, poor nutrition, and “toxic” habits contribute to abysmal American health-care outcomes. But maybe the American attitude toward health care is not the fundamental cause. This attitude might be a reflection of larger social and cultural forces in our country.

Americans have long been known for entitlement and a flair for dramatic heroism. Our health-care system amplifies those traits, with its emphasis on high-cost and high-intervention care over preventative care and lifestyle changes. We demonize figures of authority and are inherently skeptical of advice from experts. Easily offended, we insist on ensuring comfort rather than knowing truth.

Creating cultural change will require far more than simply modifying health-care incentives. Treating the problem is usually more difficult than treating the symptoms.

David J. Berman, M.D.

Baltimore, Md.

Formal international comparisons consistently point to the much higher prices paid in the United States for medical services as the primary culprit behind our high medical spending. Prices paid in the U.S. far exceed those paid abroad even as Americans consume fewer units of service (such as doctor visits) relative to the OECD average. Were overconsumption the cause of our overspending, we might argue about why—are Americans, as David Freedman contends, both unhealthy and too demanding, or are we the victims of pill pushers, greedy doctors, and the wasteful disorganization of health care?

But one cannot possibly attribute overpricing to unhealthy behaviors. In fact, our behaviors are no less healthy than peer countries’. Yes, we lead the developed world in obesity (though Europe is not far behind), but we have one of the lowest smoking rates and consume less alcohol per capita than most European countries.

Jon Kingsdale, Ph.D.

Jamaica Plain, Mass.

For the most part, David Freedman hits the nail on the head. As a neurosurgeon, I know all too well how difficult some patients can be.

Mr. Freedman postulates that Medicare for All would provide an incentive to push “patients to embrace care that’s less flashy but may do more good” by “refusing to pay for unnecessarily expensive care.” Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. The problem is that much of medicine falls outside of established clinical guidelines. Very few conditions have treatment algorithms that have been tested in well-designed studies. In fact, physicians are surprised when patients seem to adhere to the “textbook.”

Decisions regarding medical care come about through the patient-physician relationship. As Mr. Freedman says, this relationship isn’t always healthy. However, inserting governmental control to artificially diminish “unnecessarily expensive care” will only strain this relationship further and lead to greater dissatisfaction on both sides. Mr. Freedman correctly identifies one of the problems in American health care; he is just incorrect when he alludes to a solution.

Anthony DiGiorgio, D.O., M.H.A.

New Orleans, La.

It’s one thing for a medical-data wonk (or a physician who follows what these wonks say blindly) to declare that a treatment is unnecessary and/or expensive. It’s quite another thing for the patient. Say you’re a patient who desires a treatment that will extend your life by only a few months to a year, is very expensive, has nasty side effects, and may not succeed. But it’s really, really important for you to see a family member graduate from high school or college; to attend a family member’s wedding or a reunion; to cross off items on your bucket list. It doesn’t matter if your “quality of life” as defined by some arbitrary measure declines.

Even if your chance of survival is only 20 percent, 15 percent, 10 percent, or 5 percent, why should you be denied that chance?

Sue McKeown

Gahanna, Ohio

David H. Freedman replies:

To say U.S. health care is expensive because, as Jon Kingsdale notes, its prices are high is nearly a tautology. Why are they high? If the cause were an evil, greedy health-care industry, then the industry must be raking in massive profits not seen in other countries. But most hospitals are nonprofits, insurance companies (which cover just two-thirds of Americans) have profit margins around 5 percent, and Big Pharma companies are multinationals that sell their drugs all over the world—are they evil and greedy only in the U.S.? There are in fact many reasons for high prices here, and the evidence makes clear that a big one is the demanding, neglectful attitudes of American patients. (Though, yes, lower rates of alcohol consumption and smoking are relative bright spots in an otherwise troubling picture.)

Education Isn’t Enough

Like many rich Americans, Nick Hanauer used to think better schools could heal the country’s ills—a belief system he calls “educationism.” As Hanauer wrote in July, he has come to believe that he was wrong; fighting inequality must come first.

It’s about time somebody spoke up and named the elephant in the room. That the person who wrote this article is essentially the “elephant” makes it all the more laudable. I commend Nick Hanauer for taking on this issue, as it is the issue concerning educational inequality and the “achievement gap” so often spoken of. I sincerely hope that he sparks a real national dialogue about the treacheries of wealth inequality, and that the obvious response is a fundamental redistribution of wealth.

Catherine Jones

Hamden, Conn.

There is undeniably a problem with income inequality in this country, and I feel it personally as a middle-class engineer. However, I still consider myself an educationist. Nick Hanauer is dead right in saying that “a college diploma is no longer a guaranteed passport into the middle class,” but it does produce a better-informed electorate that is demonstrably less likely to vote for politicians or policies that just aren’t functional. Most pragmatically, education policy is perhaps the major institutional change (besides infrastructure improvement) most likely to get past the legislative graveyard that Congress has become.

Robert Hodge

Georgetown, Colo.

I agree with all the points made in this article. However, in one sense the failure of our education system is responsible for the state of our economy and society: the consistent lack of civics education. We have, both by design and through inattention, produced two generations ignorant of how our society and government should work. The lack of civic engagement allows the wealthy and powerful to disenfranchise huge masses of Americans.

Howard Schneider

Portland, Ore.

Nick Hanauer’s article highlighted the chicken-or-egg dilemma of education and income. However, without addressing deliberate efforts that keep certain portions of our society poor, his “fixes” won’t work. Racial animus is one of the most powerful drivers of inequality. Not until we truly have education equity along with nonbiased policing, no redlining of communities, a realistic tax system, reproductive rights, and full voter agency for all citizens will we have income equity.

Sharon Feola

Hansville, Wash.

“Educationism” as described by Nick Hanauer is a belief we are all too familiar with and guilty of ourselves as philanthropic leaders. Too often we jump to solutions before examining the root causes of the inequities that are present in our education system.

While household income is a predictor of educational attainment, structural racism is the enduring impediment that undergirds the wealth and educational opportunity gaps across our country. If we truly want to address economic inequality and fix our schools, we need to examine why such gaps exist.

Nick Donohue

President and CEO, Nellie Mae Education Foundation

Quincy, Mass.

John H. Jackson

President and CEO, Schott Foundation for Public Education

Quincy, Mass.

Finally, a fresh, realistic perspective on what is really going on in many of our underperforming schools. I taught elementary school in Boulder, Colorado, and Erie, Pennsylvania. The experiences were night and day. Both schools, in my opinion, had adequate economic resources; the difference was the income and education levels of the students’ parents. In Boulder I wanted for nothing, and going to school each day was a joy. It’s easy to be a great teacher when you have super-prepared children. In Erie I saw firsthand how money in schools doesn’t negate the effects of poverty. All the stressors in the home come right to school, which is something no amount of money can change.

Tina Brown

Moorpark, Calif.

Rather than simply acknowledge that his “educationism” approach to improving public education might have been wrong, Nick Hanauer concludes that his investment in education was wrong.

I agree with Hanauer that our education system can’t compensate for a failing economic system, but strategic interventions and investments can strengthen existing public schools in ways that afford poor children access to the same high-quality educational opportunities that their middle-class and wealthy counterparts have. I hope Hanauer will reassess his investment in education and understand that economic and educational equality are intrinsically linked.

Caro G. Pemberton

Santa Rosa, Calif.

Correction

“

Raj Chetty’s American Dream” (August) stated that the Mayo Clinic is located in Minneapolis. The clinic’s Minnesota campus is in Rochester.