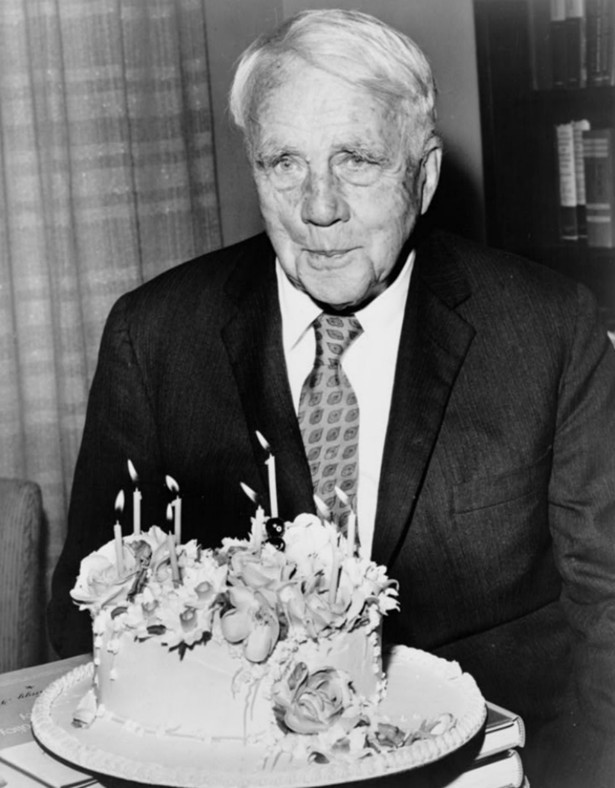

The timeless American poet was born 142 years ago today. Frost was plainspoken, pastoral, coolly melancholy, and as easy to misread as he is to quote. He shares these attributes with A.E. Housman, an English poet also born on March 26. And they’re in good company: It’s also the birthday of Sandra Day O’Connor, Diana Ross, and Leonard Nimoy, among other illustrious folks. If any day’s events were to make me believe in astrology, it would be the birthdays of March 26.

But back to Frost. He was born in 1874 in San Francisco and suffered an unstable childhood and young adulthood marked by depression, frustration, and loss: the death of a father, the death of a child. As James Dickey writes in our November 1966 issue, he “settle[d] on poetry as a way of salvation” and pursued it “with a great deal of tenacity and courage but also with a sullen self-righteousness with which one can have but very little sympathy.”

In 1912, Frost submitted some of his early poems to The Atlantic, which rejected them. According to Peter Davison in our April 1996 issue, that “ambiguous snub rankled in Frost’s memory.” (You can read “Reluctance,” one of the rejected poems, here.)

In 1915, however, the English critic Edward Garnett came across Frost’s collection “North of Boston” and became convinced “that this poet was destined to take a permanent place in American literature.” In our August 1915 issue, Garnett praised Frost’s “quiet passion and spiritual tenderness”:

He is a master of his exacting medium, blank verse—a new master. The reader must pause and pause again before he can judge him, so unobtrusive and quiet are these effects, so subtle the appeal of the whole. One can, indeed, return to his poems again and again without exhausting their quiet imaginative spell. … The poet has known how to seize and present the mysterious force and essence of living nature.

Three of Frost’s best-known poems—“The Road Not Taken,” “Birches,” and “The Sound of Trees”—appeared for the first time alongside Garnett’s essay, and Frost’s American career (he had been living and working in England when he published his first two collections) took off soon after that.

But the Frost poem that feels most relevant to Atlantic readers today is “Mending Wall.”

Back in 1915, Garnett declared it “stamped with the magic of style, of a style that obeys its own laws of grace and beauty and inner harmony.” A hundred years later, Frost’s wall seems to embody the “vindictive protectiveness” that Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt object to in our September cover story “The Coddling of the American Mind.” It’s a structure built to protect, but it creates apparently needless divisions, assuming harm—and maybe doing it—where there was no real danger to begin with.

The poem’s narrator, who has met his neighbor to repair the wall that divides their properties, is unsettled by the lack of trust the wall implies: “My apple trees will never get across / And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.” He’s worried not just about lack of openness, but also about ignorance; he doesn’t even “know / What I was walling in or walling out / And to whom I was like to give offense.”

Meanwhile the neighbor, who sticks to an old saying that “good fences make good neighbors,” “moves in darkness” because he refuses to reexamine his beliefs. And this refusal is described in a way that implies what the harshest critics of “coddled” students have: a lack of personal growth or development. Indeed, unenlightened and unevolved, he’s compared to “an old-stone savage” (a word that yes, does trigger my defenses). As if the wall surrounds his attitudes, “he will not go beyond.”

This feels like a moral. Yet as a Daily Dish reader put it in 2010, “A poem can be simply wrought while not being simple, and that is one of the things that makes Frost's work so beautiful.” And I can’t help but think that in “Mending Wall” there is something more going on than a plain condemnation of fearful barriers. Writes Mark Van Doren, in our June 1951 cover story:

Good fences make good neighbors—each knows where he is and what confines him. Without a wall between them, each would confuse himself with the other and cease to exist; or if there were fighting, it would be too close—a mere scramble, in which neither party could be made out. Distance is a good thing, and so is admitted difference, even when it sounds like hostility. For there can be a harmony of separate sounds that seem to be at war with another, but one sound is like no sound at all, or else it is like death.

Frost died in January 1963, and that October, John F. Kennedy spoke to honor Frost’s place in America’s history and future. (The president himself died a month later.) Kennedy’s remarks, published in our February 1964 issue, likewise turned to the value of a certain degree of isolation, the importance of protecting individual vision and judgment:

When power corrupts, poetry cleanses, for art establishes the basic human truths which must serve as the touchstones of our judgement. The artist, however faithful to his personal vision of reality, becomes the last champion of the individual mind and sensibility against an intrusive society and an officious state. The great artist is thus a solitary figure. He has, as Frost said, “a lover’s quarrel with the world.”

Perhaps this is the best description for the wall—a lover’s quarrel, the place where isolation and intimacy come to mean nearly the same thing. And perhaps the wall, like many students’ efforts toward social justice, is less “vindictive protectiveness” than a more productive form of conflict: an acknowledgment of barriers that attempts to reach across them too.

After all, the poem’s central task is one of mending, and Frost’s neighbors come together for the work. They repair the damage done to the wall by winter’s chill and the violent recklessness of hunters. They cajole the boulders—“There, stay where you are … !”—and cradle them in their arms. They don’t shy from pain; they “wear [their] fingers rough” on the burdens that have fallen to them, making from scattered unwieldy pieces something that marks out who and where they are.

They build selves, in other words; they come to know where they meet, what divides them. And in this work they share there is something human and healing, something of care.