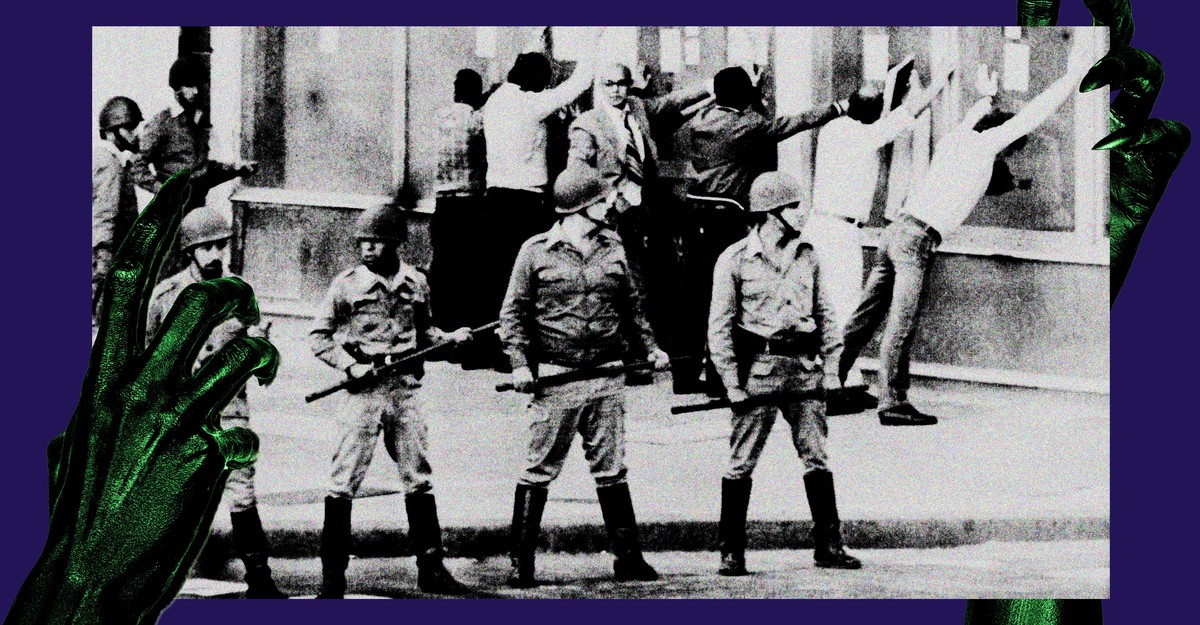

In 1976, the Argentine armed forces staged a coup against the president of Argentina, Isabel Perón. In short order, the military installed a junta that suspended political parties and various government functions, aggressively pursued free-market policies, and disappeared thousands of people over the next seven years. Victims of the regime—suspected dissidents or “subversives”—were abducted, tortured, and murdered, and many were buried in unmarked, mass graves. This period of state terror, the so-called Dirty War, has left a legacy of trauma that bedevils Argentina to this day.

The Argentine writer Mariana Enriquez’s grand, eloquent, and startling new novel, Our Share of Night, begins during this crisis and unfolds across subsequent and preceding years. We see Argentina attempt to reorient itself after years of chaos and glimpse the conditions that precipitated the turmoil. Most notable, Enriquez also shows how genre elements—including horror and the supernatural—can expand the possibilities of literary fiction. In short, Our Share of Night, Enriquez’s first novel to be published in English, reveals how sometimes, only fiction can fully illuminate the monstrous, indescribable, and ultimately shattering aspects of our reality.

The novel begins in Argentina in 1981 as the Dirty War is coming to an end. Juan Peterson and his young son, Gaspar, are urgently fleeing from, or heading toward, something. What we detect, almost immediately, is that Juan is endowed with unusual abilities. When a waitress at a diner asks Gaspar where his mother is, Juan feels “the boy’s pain in his entire body.” It is “primitive and wordless, raw and vertiginous.” Later, when Juan and Gaspar check into a hotel, we learn that Gaspar might be similarly gifted—as they’re walking down a hallway, Gaspar senses an otherworldly presence and “instead of avoiding it … he was drawn to it and was going toward it.” Juan manages to pull his son away, but he mourns the fact that Gaspar is burdened with “an inherited condemnation.”

We soon learn that Juan’s wife, Rosario, recently died in a grisly bus crash. Juan, it turns out, is a medium, and he has been trying to communicate with Rosario’s spirit since her passing, without success. Juan and Gaspar eventually arrive in Puerto Reyes, where Juan has been called to channel a force known as “the Darkness,” a supernatural entity that feeds on humans—in Juan’s words, “a savage god, a mad god.” He and Gaspar are in town to participate in the annual Ceremonial, a ritual during which the most potent occult families in Argentina attempt to summon the Darkness and draw power from it to maintain their status. Juan is, at this point in the story, the only person who can actually channel the Darkness, and he is thus forced to commune with it at the behest of the occult elite.

This novel operates as a kind of radio, constantly switching among stations. At moments the main narratives pipe through clearly, and at others we find ourselves attuned to staticky, liminal frequencies. This is a haunted story, and Enriquez has given voice to the victims of the Dirty War, and the generations that were harmed by its legacy. An infinite scroll of carnage and death plays in the background of this book: Juan and Gaspar observe a succession of ghostly presences (including one who “had no hair and wore a blue dress”), and Tali, Rosario’s half sister, sees spirits while consulting her tarot deck. Juan describes these apparitions as ghosts of the dead. “There were a lot of echoes now,” Enriquez writes. “It was always like that in a massacre, the effect like screams in a cave—they remained for a while until time put an end to them.” The dead are never far away. Our Share of Night features a cast of alluring characters enmeshed in a crackling story, but it is also, in so many ways, a book about how violence haunts and destabilizes a civilization.

Many of the set pieces in this novel—the occult ceremonies, the various acts of invocation—will scan to certain readers as genre flourishes, genre having somehow become a catchall term that, among other functions, consigns unfamiliar ways of being and living to imaginary realms. Yet this novel—powered by urgent, image-drenched language rendered beautifully by the translator Megan McDowell—convincingly captures what it feels like when your life is suddenly interrupted by a series of events that are so unimaginable and devastating, they seem unreal. It turns out that a surreal event is best described in surreal terms.

Enriquez employs this strategy to stunning effect during the Ceremonial, as the participants prepare a sacrifice for their lord:

Those who were given to the Darkness had their eyes blindfolded and their hands tied, and they stumbled. Drugged and blind, they had no idea what was before them. Maybe they expected pain. Tali saw a young, very thin man who was completely naked. He was crying, more awake than the others, and his lips trembled. Where are you taking us? he shouted, but his cries were drowned out by the panting of the Darkness and the murmuring of the Initiates.

This passage clearly evokes the experiences of those who were killed throughout the Dirty War, sacrificed to serve a god they could never appease. The god, of course, is power; indeed, this scene could be a metaphor for the tragedies throughout human history in which untold numbers of people were killed by demagogues and autocrats determined to eliminate any hint of opposition. Yet what Enriquez seems to suggest throughout the book is that such episodes are not mere tropes. During the Dirty War—as during the Holocaust, the transatlantic slave trade, and the genocide of Indigenous Americans, among many other examples—our worst, most unrelenting nightmares ceased to exist only within the realm of our imagination. They became real.

Our Share of Night is an expansive novel; it is about 600 pages long and roams from Argentina in the 1980s to 1960s London and back to Argentina in the ’90s. Enriquez, already renowned by English-language readers for her short fiction, proves that she can paint boldly and strikingly on a much larger canvas, and she invites us to witness her characters as they grow and love and sin and die. Yet the wonder of this book is that she shows us, time and again, that the supposedly impersonal forces of terror that act on our lives aren’t as remote as they seem. Even when we believe that the monsters have taken over, Enriquez reminds us that there are always human beings at the controls.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.