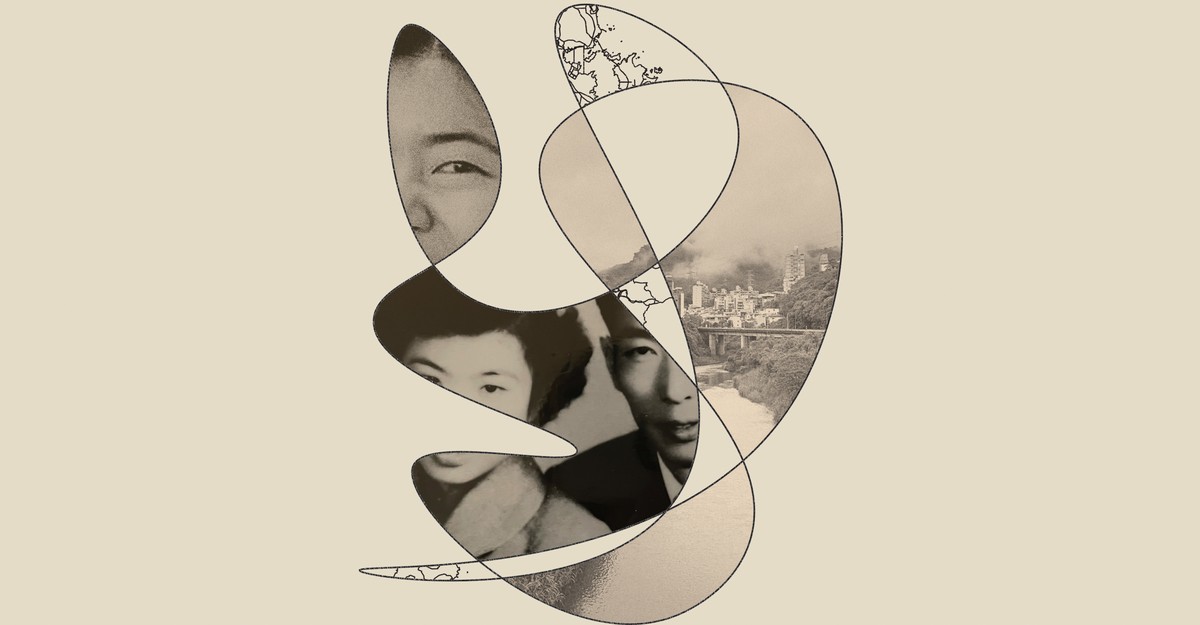

It wasn’t a great time to visit Taiwan. Nancy Pelosi’s layover in Taipei in early August had heightened tensions with China, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine had people asking whether Taiwan faced a similar threat.

My father and I scrolled through news—of aggressive Chinese military drills and endless U.S. delegations—and debated whether it was safe to go. But when weighed against a hypothetical, the reality of my grandmother’s cancer won out. She was refusing chemotherapy. We left in September; better to be early than late.

Upon landing, I found the Taiwan of my childhood summers largely unchanged. I felt silly for expecting otherwise. Almost everything was as I remembered—my grandmother’s 13th-floor apartment near Taipei’s bustling Shilin Night Market; the department store where my father’s family had run a small leather-goods shop; that one stall with gua bao, fluffy white buns stuffed with tender pork belly, and the owner who gets bossier each time I see her. The only hint of tumult was a copy of the Taipei Times in the snack aisle of a convenience store with the headline “China Unlikely to Invade Taiwan Soon.”

The media had described the atmosphere as “defiant” but, to me, it just felt normal. At More Fine, an optical shop in the central district of Gongguan where my parents and I always get our glasses, my father asked the owner why everyone seemed so calm. “It’s numbness,” he called from the back of the shop. “What else is there to do?”

As I headed over to my grandmother’s apartment, I mulled over the shop owner’s words. I felt similarly numb, frustrated by all the unfeeling analysis of the country where my extended family lives, where my parents grew up—and where my grandmother is dying of cancer. Pundits picked over Taiwan’s history and prospects, often with no personal stake in the matter. To watch a place so familiar to me be reduced to foreign-affairs talking points was disorienting: “the most dangerous place on Earth”; “a progressive, thriving democracy”; “safe until at least 2027.” I was angry that we had to think about this at all, that the burdens of living and dying were not enough.

With my grandmother, though, the present was all that mattered. I sat by her side, rubbing her back as I listened to her life story, which I was determined to record before I left. I placed my phone on my knee as I yelled questions into her ear. Her hearing is poor, but her memory is surprisingly clear.

She remembers, for instance, the two other Taiwanese women who were in love with my grandfather. They had all worked in the homes of U.S. soldiers based in Tianmu during the 1950s. The prettiest of her competitors, she told me, had rosy skin and brilliant dancing skills.

But my grandfather, a cook, pursued my grandmother, a shy housekeeper. “I was the most pitiful, but I was diligent and good,” she said. She noted his neatly made bed and the books on his desk; he was a man who wanted to rebuild, who was hardworking and well mannered. He began sending her braised pigs’ feet from a local stall, later bringing her scallops and other delicacies that she had never tried before. “They were delicious!” she said with a mischievous chuckle.

But she had also read the loneliness in his shoulders. Before they married, he told her about his wife and two young children lost to him on the mainland. They were one of many families separated in the chaos of the Communist takeover in 1949, when he became stranded in Taiwan. The Nationalists swiftly enacted a no-contact policy with China that would last for decades, its bans on travel and mail communication cleaving families in two. My grandmother—a benshengren born in Taiwan marrying a waishengren from China—accepted it all, including the photo of his other family that he kept in his wallet. “When I was little and I didn’t understand,” my mother once told me, “I’d sneak my photo into his wallet too.”

He proved a dedicated husband and father to their five children. As soon as he finished work, he headed back to their small apartment, which she scrubbed clean and decorated with flowers. “Our home was the prettiest, the cleanest,” she boasted. “While the kids did their homework, he would sit with them, sharpening their pencils by hand.” They rarely fought. She credits him with giving her a happy life—one that she, as an adopted child treated poorly by her family, could not have imagined for herself. “I was the most blessed,” she kept repeating to me. “Life with your grandfather was blessed.”

One thing that my grandmother didn’t bring up—but that my mother had told me about years earlier—was the trip my grandfather made to see his first wife and daughter in 1985. (His son had died by then.) The women had traveled from northeastern China to Hong Kong, where my grandfather’s brother lived; my grandfather met them there.

My grandmother packed sweaters and mangoes and money that they couldn’t spare into my grandfather’s suitcase for his week-long trip. He’d had a stroke, and was unable to walk without a cane. “It was an impossible trip,” my mother said. “But he made it happen.”

A week after returning to Taiwan, my grandfather died. When I asked my grandmother how his visit to Hong Kong had made her feel, she told me that he had gone to see his brother. When I asked again, she changed the subject.

I flew home on my grandmother’s 87th birthday. Before I left, she patted me on the arm and told me not to worry. “Your uncle and aunts will take care of me, as will all of your cousins,” she said. I thanked her, and told her to bao zhong, take care.

But I do worry—about how the cancer will bloom, about whether normal life in Taiwan will continue. I think of how my grandmother has to rock her weight between the dining chairs to reach the kitchen, how she wouldn’t be able to escape if war broke out. And I wish, perhaps uselessly, for a world that would care about Taiwan even if it weren’t a beacon of democracy in Asia or an essential producer of semiconductors or a pawn in a great-power play. A world that could peer into the warm glow of my grandmother’s apartment—my aunts laughing as my nephews scramble over the couches and pull funny faces, all of us finally together. I wish that could be enough.

This article appears in the January/February 2023 print edition with the headline “I Went to Taiwan to Say Goodbye.”