In the digital age, the concept of a physical archive may seem outdated. Making multiple trips to a library has none of the convenience of searching for information online. But digitizing records isn’t a perfect solution, Alexis C. Madrigal writes, because it may make researchers overconfident that they’ve seen everything, and, as the historian Lara Putnam says, it “decouples data from place.” Still, whether they are scrutinized in person or on a computer, archives have preserved historical moments—via notes, letters, and photographs—for hundreds of years.

The Jack Kerouac archive briefly digitized parts of its collection in 1998, but spending time with his diaries and notebooks in person provides a detailed image of him, including his mindset while he traveled across the country for his second novel, On the Road, Douglas Brinkley found. Physical documents can help us understand individuals from the past, while capturing the world in which they lived. Stephen Kotkin attempts to tackle both a man and his moment in his biography of Joseph Stalin, making use of Soviet archives that were not opened until many decades after he was in power. He paints a colorful picture of Stalin himself, but also of his contemporaries, such as Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky.

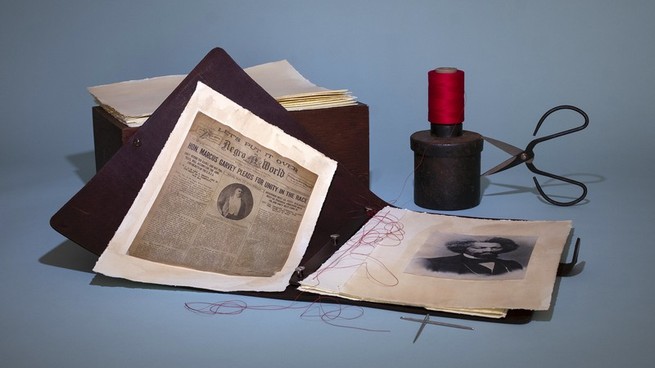

Like Kerouac, the photographer Baldwin Lee also hit the road to see what America had in store for him. But that’s where any potential similarities end, writes Casey Gerald, as Lee’s photographs of Black life in the American South represent the work of “a man who knew he didn’t know a goddamn thing—and chose to change that.” Capturing ordinary moments in life is a powerful endeavor, especially when they highlight people historians didn’t chronicle; William Henry Dorsey’s scrapbooks depicted the world of 19th-century Philadelphia and served as inspiration for intellectuals like W. E. B. Du Bois. Lee and Dorsey, like many others, made the conscious effort to create time capsules for the future—ones that we could look back on long after they died.

Every Friday in the Books Briefing, we thread together Atlantic stories on books that share similar ideas. Know other book lovers who might like this guide? Forward them this email.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What We’re Reading

Print Collector / Getty / Farknot Architect / Shutterstock / The Atlantic

The way we write history has changed

“I’ve spent a lot of time in archives. They make me feel like a pilgrim of a very obscure religion, and the process shares the features of other sacred journeys. You put your things in a special locker, keeping only laptop, phone, pencil. You’re inspected for purity on the way into the sanctum and instructed in a series of obscure rights and responsibilities that attend to touching this very special paper. The rooms are beautiful. No one talks. Everyone is on a secret mission, just like you.”

Katie Martin / The Atlantic

“But if Kerouac is not unfamiliar, he may nevertheless be underknown. Much of what he wrote has never been published. Indeed, much of what he wrote has been seen and read by only a handful of people. These unpublished materials, including letters, notebooks, and a voluminous diary that he started at the age of fourteen, are lodged in a bank vault in Kerouac’s home town, Lowell, Massachusetts.”

???? The Portable Jack Kerouac, by Jack Kerouac, edited by Ann Charters

???? Kerouac: Selected Letters, by Jack Kerouac, edited by Ann Charters

Simon Prades

“Politics still influence how [Stalin] is publicly remembered: in recent years, Russian leaders have played down Stalin’s crimes against his own people, while celebrating his military conquest of Europe. But the availability of thousands of once-secret documents and previously hidden caches of memoirs and letters has made it possible for serious historians to write the more interesting truth.”

Untitled (1983–1989) (Copyright Baldwin Lee. Courtesy of Hunters Point Press / Howard Greenberg Gallery.)

A more complete archive of the American South

“Lee made those 10,000 images because he knew the limits of a single frame. He knew that even 10,000 could not tell it all. This, I believe, is the promise of archival recovery: We can get a fuller glimpse of lives like White’s, which are so often flattened into stock figures, if not outright farces. We can start to understand their complexity.”

Lenard Smith

A priceless archive of ordinary life

“Today, other writers and scholars recognize the profound importance of materials such as the Dorsey collection—resources collected and preserved informally by African Americans at a time when white historians claimed that African Americans had no history to speak of. These historians also had little interest in the lives of ordinary people.”

???? Writing With Scissors: American Scrapbooks From the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance, by Ellen Gruber Garvey

???? William Dorsey’s Philadelphia and Ours, by Roger Lane

About us: This week’s newsletter is written by Elise Hannum. The book she’s reading next is Braiding Sweetgrass, by Robin Wall Kimmerer.

Comments, questions, typos? Reply to this email to reach the Books Briefing team.

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.