An experiment with Internet-enhanced vision reveals the best and worst of our technological dreams.

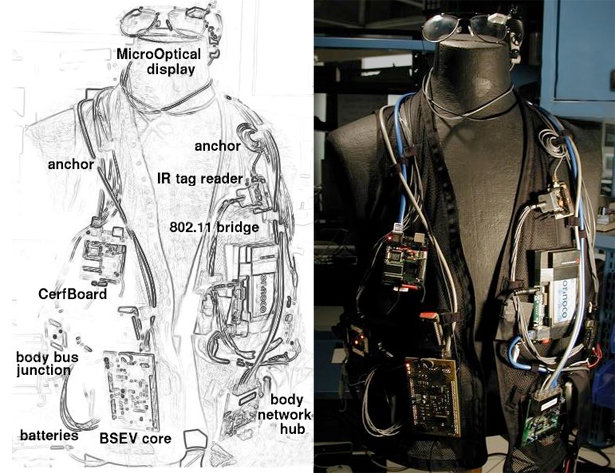

The mockup from Google's Project Glass.

On first glance, the video for Google's Project Glass has all the expected elements of a flashy, futuristic clip: the light, modern music; the glossy, slick interface; and the image of a life full of pleasure and easy socializing. We clearly recognize this future because it is our world made better and brighter, rather than more ominous and grey. It is a futurist concept meant to go viral.

At the same time, all utopian dreams express something about the dreamer. Whatever the place of modern technology in our lives, it finds expression in Project Glass and its eminently plausible vision of augmented reality. After all, that particular form of digital tech has always been the assumed apotheosis of modern gadgetry. As Andre Nusselder notes in Interface Fantasy, his 2006 work on 'cyborg ontology', our actual wish for technology is for it to supersede our bodily limitations, to escape the death drive not with self-destruction, but the birth of a new kind of techno-individual.

But that dream has in many ways already arrived. Encyclopedias accessible from smartphones inflect our conception of knowledge. GPS wayfinding changes our relationship to space. All technology--especially when we think of language as its most basic form--reshapes and reforms how we relate to that thing

called reality. It's perhaps because of this that GigaOm's Kevin C. Tofel has already noted that the glasses and their unintrusive design represent "the next logical step" in our already techno-augmented lives. It's almost as if we've always known this was coming.