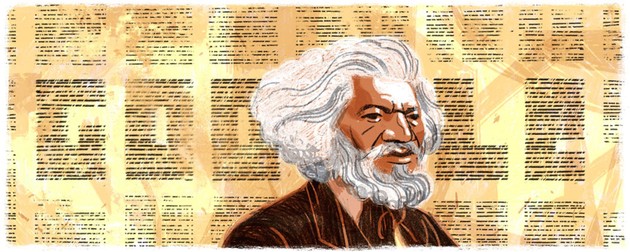

Like a president on a dollar bill, the bust of Douglass rests, regal, before a backdrop of newsprint:

That Google Doodle of the abolitionist, women’s rights activist, orator, and one of the earliest contributors to The Atlantic commemorated the beginning of Black History Month yesterday. And the drawing’s background is fitting: The written word was central to both his escape from slavery and to the broader abolitionist movement.

Douglass’s own interest in education was ignited at a young age, when his slave master read him Bible passages. Soon, he was using any means he could to inform himself. He acquired books, learned to spell, and, with coins earned from shining shoes, secretly purchased a copy of The Columbian Orator, a text that supposedly taught him about humanity and eloquence. Of this volume he wrote: “Nevertheless, the increase of knowledge was attended with bitter, as well as sweet results. The more I read, the more I was led to abhor and detest slavery, and my enslavers.”

After escaping his enslavers, Douglass dedicated himself to the cause of abolitionism, touring the country to speak, penning not one but three autobiographies, and publishing an anti-slavery newspaper called The North Star. Shortly thereafter, he began contributing to The Atlantic, where he wrote two of the magazine’s most influential articles on the rights of African Americans.

In the first one, a December 1866 article entitled “Reconstruction,” Douglass urged Congress to live up to the ideals expressed in Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural address by passing a civil-rights amendment asserting the equality of whites and blacks, and giving the blacks the vote. He wrote:

Whether the tremendous war so heroically fought and so victoriously ended shall pass into history a miserable failure, barren of permanent results,—a scandalous and shocking waste of blood and treasure ... or whether, on the other hand, we shall, as the rightful reward of victory over treason have a solid nation, entirely delivered from all contradictions and social antagonisms, based upon loyalty, liberty, and equality, must be determined one way or the other by the present session of Congress.

But Douglass had bigger plans. As he had lectured before his fellow abolitionists a year earlier: “Slavery is not done until the black man has the ballot.” So in January 1867, on the heels of his first Atlantic article, Douglass penned another case to Congress, this time arguing solely for impartial suffrage. He first appealed to logic:

The fundamental and unanswerable argument in favor of the enfranchisement of the negro is found in the undisputed fact of his manhood. He is a man, and by every fact and argument by which any man can sustain his right to vote, the negro can sustain his right equally. It is plain that, if the right belongs to any, it belongs to all.

Then to humanity:

[Negroes] have emerged at the end of two hundred and fifty years of bondage, not morose, misanthropic, and revengeful, but cheerful, hopeful, and forgiving. They now stand before Congress and the country, not complaining of the past, but simply asking for a better future. The spectacle of these dusky millions thus imploring, not demanding, is touching; and if American statesmen could be moved by a simple appeal to the nobler elements of human nature … it would be enough to plead for the negroes on the score of past services and sufferings.

Then, in one last effort, to white America’s self-interest:

National interest and national duty, if elsewhere separated, are firmly united here. The American people can, perhaps, afford to brave the censure of surrounding nations for the manifest injustice and meanness of excluding its faithful black soldiers from the ballot-box, but it cannot afford to allow the moral and mental energies of rapidly increasing millions to be consigned to hopeless degradation. … We want no longer any heavy-footed, melancholy service from the negro. We want the cheerful activity of the quickened manhood of these sable millions.

Douglass concluded with a warning:

Statesmen, beware what you do. The destiny of unborn and unnumbered generations is in your hands. Will you repeat the mistake of your fathers, who sinned ignorantly? or will you profit by the blood-bought wisdom all round you, and forever expel every vestige of the old abomination from our national borders?