American 11 passed low over the George Washington Bridge. As best the last moments inside the cabin can be reconstructed, few passengers if any were looking through the windows, or were aware of the airplane's ominous flight profile—the combination of ultra low altitude and high speed that characterized its final bombing run. The mood aboard must have been fearful but quieter now. In the back of the airplane another flight attendant was on the phone. Her name was Madeline Amy Sweeney. She had gotten through to an American flight service manager in Boston, and with exceptional cool had given him a running account of the hijacking, fingering the terrorists and confirming much of Betty Ong's account, including the slaughter of the passenger in business class. It is likely that she added important details about the terrorists' techniques—how, for instance, they got into the cockpit—which for security reasons have not been made public. Seconds before 8:46 and the impact she looked through a window to give a position report, and to her surprise saw the city flashing by. She said, "I see water and buildings!" She may have been the first person to understand the hijackers' intentions. She said, "Oh, my God! Oh, my God!"

At 5:30 that afternoon they got permission for their nascent team of unbuilders to explore the ruins firsthand.

The walk they took became famous at the site because of the forces it unleashed. About fifteen people went along, including Holden and Burton, the engineer Richard Tomasetti, and a collection of tough construction guys. Though every one of these men was accustomed to grappling with problems on a very large scale, none was prepared for a disaster so vast and severe. Wading through paper litter and pulverized concrete, they tried to approach from the north, but were blocked by heavy smoke. Few of them had respirators. They moved upwind to the Hudson, and flanked southward again, cutting through the peripheral public areas of the heavily damaged World Financial Center, a high-rise complex that stood between the Trade Center and the river. Conditions there were so strange that Holden afterward had trouble knowing where they had been, though he did remember one surreal passage through a ruined atrium restaurant where all the fire alarms were blaring, wah, wah, wah.

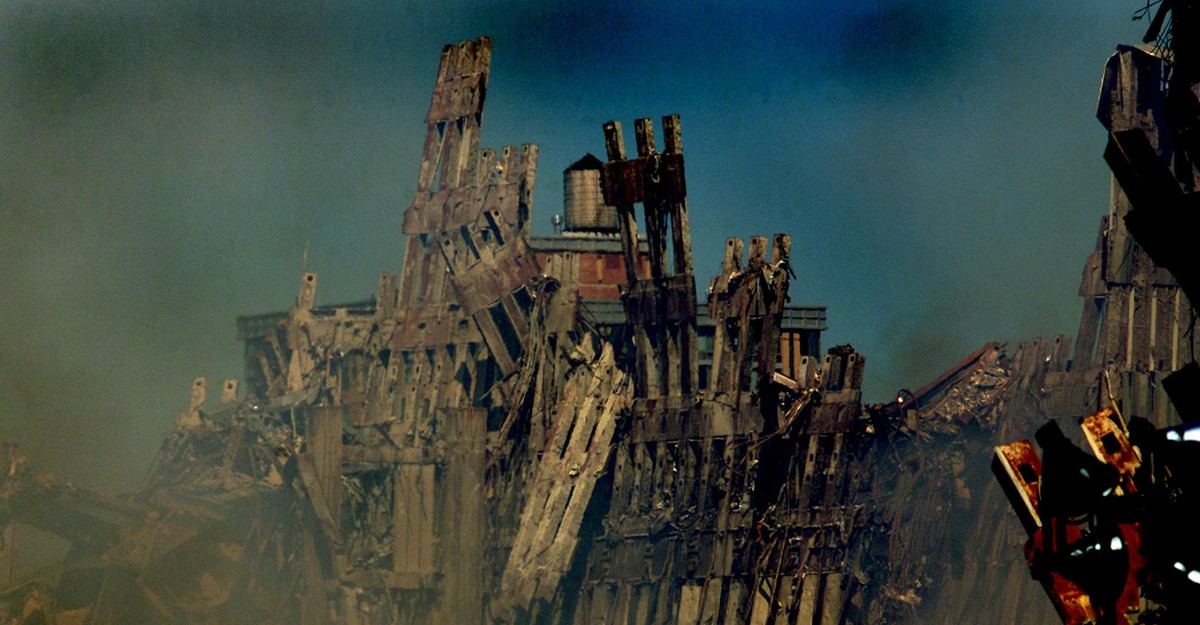

Then, through an opening between buildings, they came suddenly upon the Trade Center ruins themselves—the skeletal walls and smoking hills of rubble where the towers had been, the boxy shell of the Marriott hotel, the heavy steel spears protruding from neighboring buildings, the collapsed north pedestrian bridge, the massive external column sections thrown every which way across the streets, and everywhere the fires. For Holden it looked like a scene from Apocalypse Now. He told me, "It was hallucinogenic—quasi-druggy, with flares shooting up and death in the air. There was a sense of crazed panic, people fighting to save lives, fire hoses cascading all over the place." For the next ninety minutes they moved through a smoky twilight among the ruins. The ground was littered with hundreds of shoes, presumably from victims, but characteristically for this unusually imploded killing zone, not a single corpse lay in sight.

The last survivor found was Genelle Guzman, a thirty-one-year-old Port Authority clerk of Trinidadian origin, who had delayed with Buzzelli and the others on the sixty-fourth floor, but had gotten ahead in the descent, and was on the thirteenth floor when the building boomed and broke apart around her. She was with a friend named Rosa, and had stopped to adjust her shoe. She had put her hand on Rosa's shoulder. As the building crumbled, she felt the shoulder pull away, as if Rosa were running up the staircase. She was hit, and felt the acceleration of collapse around her. All was darkness. When the roar stopped, she heard a couple of calls from a man who then grew silent. Her head was jammed under a load of debris, but eventually she worked it loose. She was in a dark cavity in the inner world of rubble. Her legs were pinned and crushed. She felt a dead man beside her. It turned out that he was a fireman, and that there was another one, also dead, lying nearby. For twenty-seven hours Guzman lay trapped and seriously injured. She spent some of that time bargaining for her soul, pleading with God to show her a miracle. Early the next afternoon she heard a search party, and when she yelled out, a voice answered. The voice said, "Do you see the light?" She did not. She took a piece of concrete and banged it against a broken stairway overhead—presumably the same structure that had saved her life. The searchers homed in on the noise. Guzman wedged her hand through a crack in the wall, and felt someone take it. A voice said, "I've got you," and Guzman said, "Thank God." She spent the next five weeks and New York's Bellevue Hospital, undergoing reconstructive surgery on her right leg. She was the last person to emerge alive from the ruins.

The search for bodies imposed a reversal of normal sentiments about the dead, so the toughest days were those in which none were found. The firemen concentrated their efforts first on the debris where their colleagues were likely to lie, and as expected, they found pockets in the ruins of the stairwells in which the dead were piled on top of another. But the site never yielded the large concentration of victims—"the mother lode," Sam Melisi called it—that everyone was hoping for. Most of the dead were instead found "in dribs and drabs," as a discouraged fireman told me—meaning in ones and twos, and distributed all over the place. The best predictor turned out to be the nature of the materials being excavated—at one extreme the intensely compacted and burned-through ruins that hardly merited a glance, and at the other extreme the relatively loose jumbles of heavy steel, where intact bodies continued to be found until nearly the end. I remember a startling moment late in December in the "donut hole" crater of Building Six, when a grappler lifted a beam and uncovered a man in a suit and tie who had fallen from Cantor Fitzgerald, in the North Tower, and was sitting upright, now somewhat shriveled but whole, with his wallet in his pocket. His condition was surprising particularly because he had been sitting almost in the open for a few months, and had not been entombed in the pumicelike Trade Center powder that helped to preserve others. Generally, the bodies that endured best were those of firemen, because they were wrapped in equipment and heavy clothing, whereas the most devastated were those of women, whose stockings and blouses offered poor protection during the collapses and after death. But, of course, decay began to set in for all of them from the first day, and the unseasonably warm winter weather sped the process along. By January the intact bodies being found were falling apart, with heads in particular becoming detached, and at one of the morning meetings an official from the Medical Examiner's Office of the City of New York made a private plea to take greater care with the exhumations, because of the obvious undesirability of having to identify the same victim multiple times.