by JOHN MOORE

WHEN I found the cardboard box with holes in its lid awaiting me on the hall table, I took the usual precaution of holding it up to my ear, for in this way it is possible to make a rough-and-ready diagnosis of the contents of such boxes with which kindly neighbors humor the whim of amateur naturalists. If there is a scrabbling of little feet, I expect to find a lizard, a bat, a field mouse, or a mole trying to dig his way through the bottom of the box with an action like the breast stroke of a strong swimmer. If there is a buzz or a frantic drumming of wings, I take care to shut the windows before I look inside the box, for the captive will probably turn out to be a butterfly, a hawk moth, a cockchafer, one of those big dragonflies which look like dive bombers, or even an infuriated hornet.

On this occasion, however, there was no sound at all neither feet nor wings nor squeak nor chirrup; and that meant, in my experience, either that the prisoner was a caterpillar or that it was moribund: a shrew, perhaps, chewed by a cat, a nestling fallen out of a tree, or a leveret partially decapitated by the scythe. I opened the box anticipating that I should have to put something out of its misery.

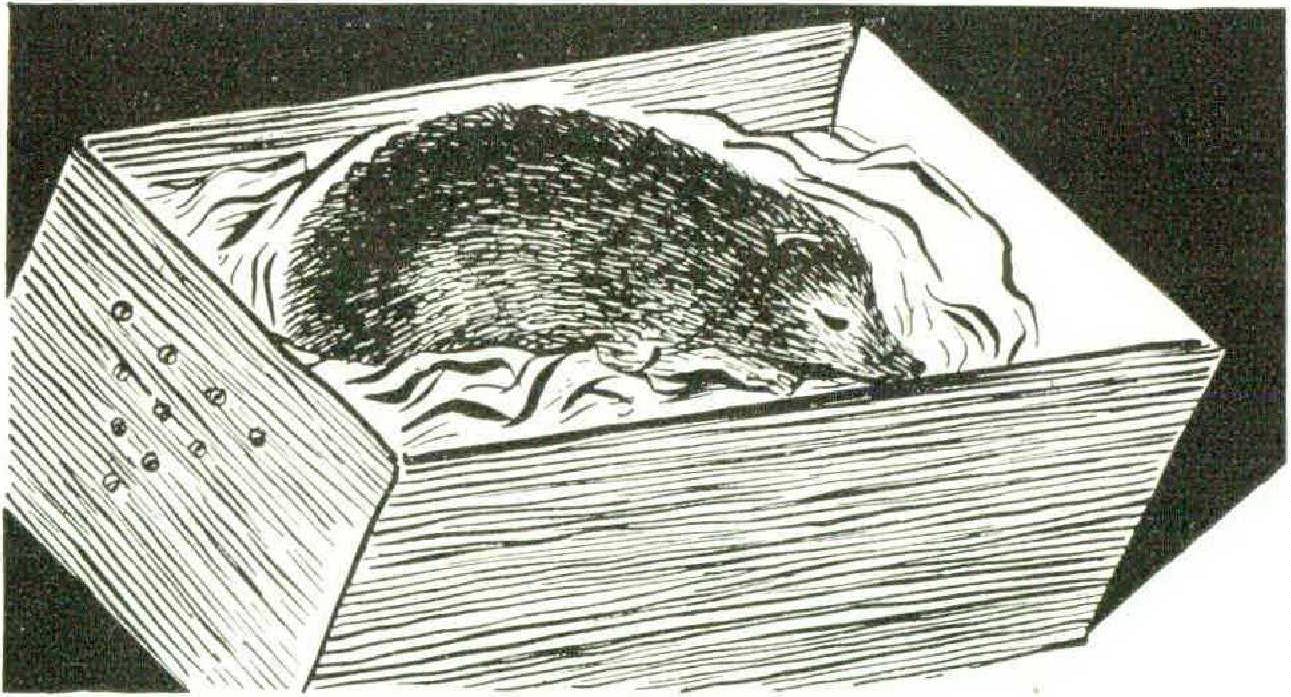

But as it turned out, the little beast inside it looked far from miserable; he was without exception the most contented little beast I had ever seen. He had made himself, already, a neat and cozy nest out of mosses and ferns which his captors had thoughtfully provided, and he lay there sleeping, nose to tail. When the light fell upon him, he stirred slightly and yawned. He was a very small hedgehog, so young that his prickles were not yet prickly, and were no stiffer than coarse hair.

The first thing to do, when little beasts arrive in cardboard boxes, is to feed them; so I put some milk in a fountain-pen filler and held it adjacent to the baby hedgehog’s nose. His response to this trifling kindness endeared him to me immediately. Without opening his eyes, he widely opened his mouth; and without troubling to move his body, which was arranged so comfortably in the improvised nest, he sucked and sucked until the fountain-pen filler was dry. Then he licked his nose with a pink tongue, closed his mouth, and resumed his slumbers.

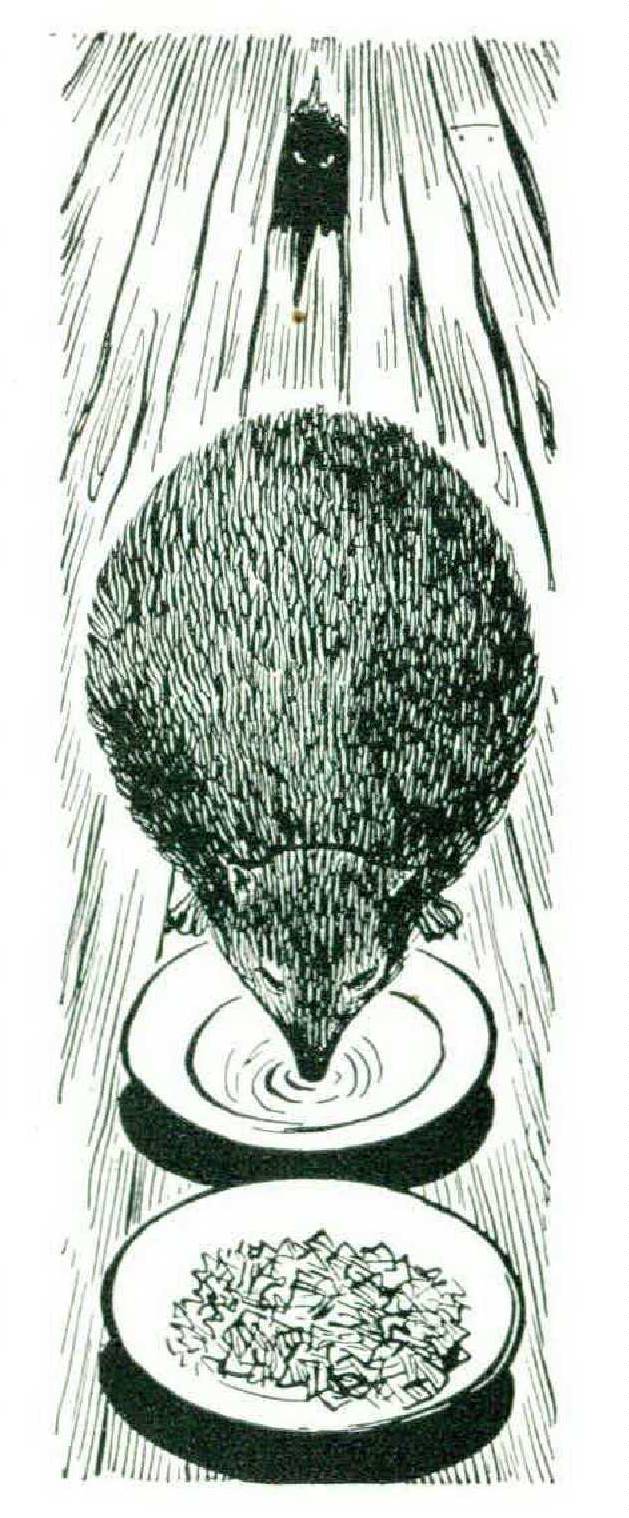

This trustful acceptance of fate, this attitude of “open your mouth and shut your eyes and see what the good Lord sends you,” this touching confidence that the world had nothing but good in store for him, was characteristic of the small urchin throughout his short life. When he grew too big for the box, he lived for a time among a pile of old clothes in a corner of our sitting room. Accepting without question this bigger and better bed as a gift from the kindly providence, he straightway made a new nest and promptly went to sleep in it. We placed a saucer of milk in the fireplace at the other end of the room, and two or three times a day, for our own amusement or for the entertainment of visitors, we removed the hedgehog from His nest and carried him across to the saucer, lie never bothered to open his eyes to see what, was in it. If it had contained hemlock or arsenic, he would have trustfully lapped it up. When he had drunk the lot, he turned round, opened his eyes at last, and waddled slowly back to his nest. He had discovered, while only a few weeks old, the secret of perfect happiness. He feared nothing and questioned nothing, desired nothing more than he had, ate and slept, and dreamed no dreams.

His ponderous waddle, when he was on his way home full-fed from the saucer, resembled the action of a slightly drunken sailor; his hindquarters, as he walked, swayed gently from side to side. His brief and rather fat gray tail, and the genial appearance of his undulating backside, reminded one somewhat of a miniature elephant, and this got him his name. He was undoubtedly a Hedge Elephant, declared my wife; and improving on this next day, she christened him Elehog.

Although he was far too wise ever to go out of his way in search of anything that didn’t fall into his reach like manna from heaven, he soon became both inquisitive and acquisitive about things which he happened to find in his path during his journeys from the saucer to his nest. If they seemed edible, he ate them; if not, he carried them home. Thus, when he encountered in the fireplace some paraffin fire-lighters, he devoured nearly half of one before we saw what he was up to and dragged him away; and apart from acting as a gentle purge the strange meal did him no harm. If he met with a pair of boots he would always lick the polish off them before proceeding on his way. As for less edible things, he seemed to like them for their own sake and not for their utility, as misers love their gold; for if he found a matchstick he would pick it up, carrying it in his mouth like a retriever, and take it to his nest, where he kept a little pile of matchsticks, bits of string, ribbons, cinders, and scraps of paper. But I repeat, he never deliberately sought these things; that would have been far too much trouble, that would have been a waste of precious eating and sleeping time, that would have been incompatible with the dignity of a small Elehog.

It is often said that hedgehogs are excessively verminous, but we never found any fleas on Elehog, although he would sometimes pause in the course of his slow and dignified walk home to scratch himself in a contemplative way, with his hind leg. Anyhow, Elehog’s stiffening bristles gave shelter to nothing that jumped or crawled; and it was for quite a different reason that he had to be banished from our sitting room. His little messes, which were bright green, unfortunately did not match the green of the carpet; so his nest was removed to a back room where, in his easygoing and contented fashion, he quickly settled down and began to add quantities of raffia and binder twine to his store of ribbons, matchsticks, and string. We had thought of turning him out into the garden, but he was still very small and we were afraid lest our neighbor’s dog, notoriously allergic to hedgehogs, might discover him before he had retired to a secret hibernaculum. Winter was coming on, and he was very comfortable in the back room. We filled a second saucer with some crisp wheat-flakes, which he carried one by one into his bed and from time to time devoured with a loud crunching noise, as if he were cracking nuts. The first, frosts, however, made him even more slumberous than he had been before, he woke up only on the mildest days and made less frequent journeys to the two saucers for a drink of milk or to collect another wheat-flake to increase his winter store. In his heap of old shirts, surrounded by his numerous and oddly assorted possessions, the little capitalist dozed on happily.

Alas, it is too harsh a world for such gentle philosophers; it is too full of roughs and toughs with hungry bellies and long teeth. In one of the floor boards of the back room there was a small hole caused by dry rot, and out of this hole one night there crawled the swift assassin. We can only guess what happened after that. Perhaps the rat, lithe and silent and terrible, crept upon Elehog as he slept, and slew him as Macbeth slew Duncan; perhaps Elehog, who was so trustful and unquestioning, accepted his murderer as merely another gift of the good providence — and went forward without fear or doubt to play a game with him. It must surely have happened that way, for Elehog’s prickles were already stiff and sharp, and they provided him with a ready defense if it had occurred to him to use it. But he had not learned — he had never needed — to use it; in all the three months he was with us we had never known him to curl up, and he would allow himself to be picked up and handled without even troubling to raise his backward-sloping spines.

I can imagine him waddling slowly towards the hateful rat and sniffing it with the same friendly inquisitiveness with which he sniffed boots and matchsticks and bits of string; and then, I suppose, it was quickly over, for the assassin had him by the throat. Poor little Elehog discovered too late what pacifists wiser than he have often discovered too late: that there is a kind of aggression which doesn’t even allow you sufficient time to turn the other cheek. You can’t reason with a rat any more than you can negotiate with a bomb.

His slayer dragged Elehog to the hole, where we found him in the morning, jammed halfway down it. bv his prickles, gnawed and bloody, with his hind legs stiffly sprawled out, and his absurd backside and his short fat elephant-gray tail ridiculously pointing at the ceiling. Nothing peaceful, nothing comforting, nothing in the least heroic about that ending; only the ancient grotesquerie of violent death, the cruel parody of a lifelike attitude, which is always the signature of the roughs and toughs when they write their sneering answer to gentle creatures who live and let live.