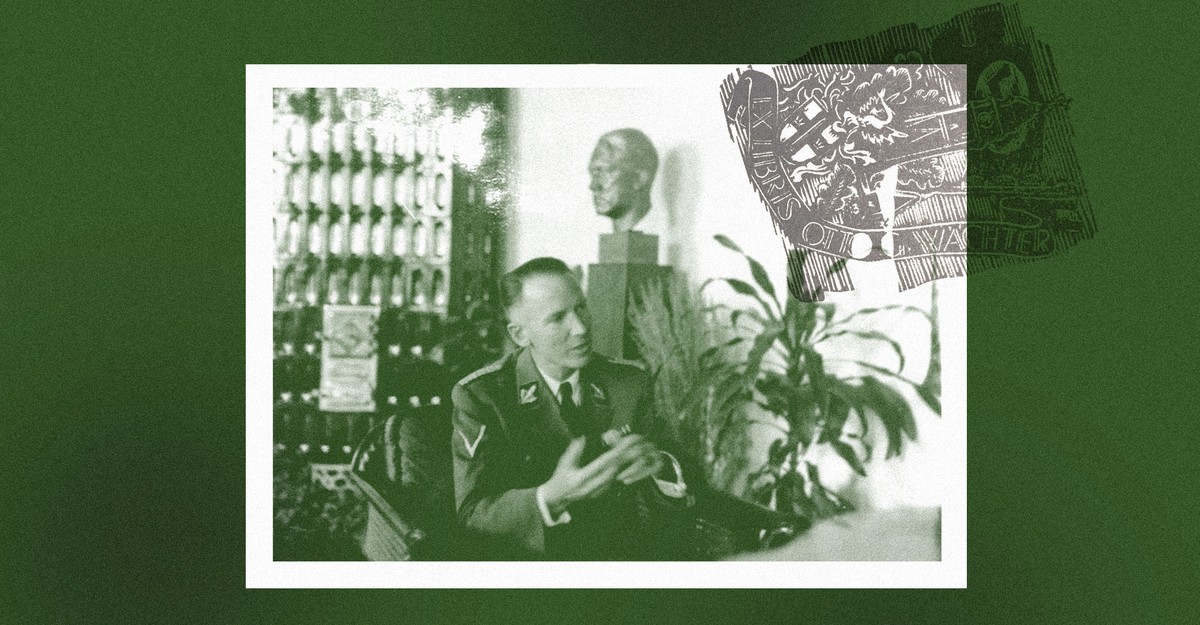

“There’s something going on here,” said Lisa Jardine, the British historian, as she scrolled on a laptop through a digitized cache of letters, ochre with age. “The sheer volume. It’s rare to have so many, even between a husband and wife. Almost daily. Volume is often a form of concealment. It’s harder to make out what the writer is trying to hide.” The letters—many hundreds of them—had been written by SS Gruppenführer Otto von Wächter, a high-ranking Nazi, and his wife, Charlotte, correspondence that spanned a period from 1930 until Otto’s death, under suspicious circumstances, in Rome in 1949. Wächter, indicted for mass murder, had been in hiding since the fall of the Reich, sheltered in his last days by a powerful bishop. The letters had come into the hands of Philippe Sands, a prominent human-rights lawyer, who was seeking Jardine’s help in bringing them to wider attention.

It was the summer of 2015. Sands, a friend, was at work on what would become his award-winning book East West Street. My wife and I were in London, and Sands asked if we’d like to join him on a morning visit to see Jardine. She was a legendary figure: Renaissance scholar, historian of science, director of the National Archives, fan of the Talking Heads, and all-around woman of affairs. Among other things, she had for six years chaired Britain’s Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. Her home was on a shady street around the corner from the British Museum, its red-brick Victorian countenance relaxing into a bright and airy interior.

Jardine was gravely ill—she had only a few months to live. But you wouldn’t have known it. She served coffee and pastries. She was sharp, funny, and clearly tantalized by the project Sands laid before her—as he suspected she would be. For the past several years she had been running the Centre for Editing Lives and Letters at University College London. Jardine sat on a couch in a loose gown, the laptop balanced on her knees, dipping into the Wächter trove while voicing asides about her experience reading the voluminous correspondence of Elizabeth of Bohemia (“a woman who should be much better known”). On one level, the correspondence embodied a love story—Charlotte and Otto were devoted to each other. It is filled with domestic details. But there was a bigger story locked in the Wächter letters, Sands believed, particularly as they related to the postwar years, when Nazi war criminals were fleeing to South America and elsewhere. Some of the so-called ratlines that helped them on their way ran through the Vatican, among other places. Intelligence services from many nations prowled Rome’s streets and palazzos. How did Otto von Wächter fit into all this?

Jardine did not need persuading. Sands left with her blessing (and support). The task of translation and analysis, together with interviews in Germany, Austria, and Italy, would occupy him for the better part of two years. He was assisted by a young scholar, James Everest, who had studied with Jardine—her last Ph.D. student. One result of this effort is a BBC podcast, The Ratline, which has just begun, with Stephen Fry and Laura Linney reading the letters between Otto and Charlotte. There will soon be a book. The series is dedicated to Lisa Jardine.

Philippe Sands had happened upon the cache of letters by chance. His book East West Street is centered on the city known variously (depending on decade and sovereignty) as Lemberg, Lwow, or Lviv. His grandparents had come from there; much of the rest of the family perished in the Holocaust. The city was also the home of two great theorists of atrocity and the law—Rafael Lemkin, who gave us the concept of “genocide” and found refuge in America, and Hersch Lauterpacht, who gave us “crimes against humanity” and found refuge in Britain. All of these strands are woven into a book that is part memoir, part biography, part history, part philosophy.

One man who figures prominently in the Lemberg story, and in the book, is Hans Frank, Adolf Hitler’s personal lawyer, who in 1939 became governor-general of the occupied Polish territories, living in Krakow’s Wawel Castle and aggressively rounding up, transporting, and killing the Jewish population in areas under his control. Frank would be convicted of war crimes at Nuremberg. He was hanged in 1946. His son Niklas bore him no love and published a devastating portrait, Der Vater, in Germany in 1987. (The book was published in English a few years later under the title In the Shadow of the Reich.) To this day, Niklas carries in his wallet a picture of his father taken after his execution.

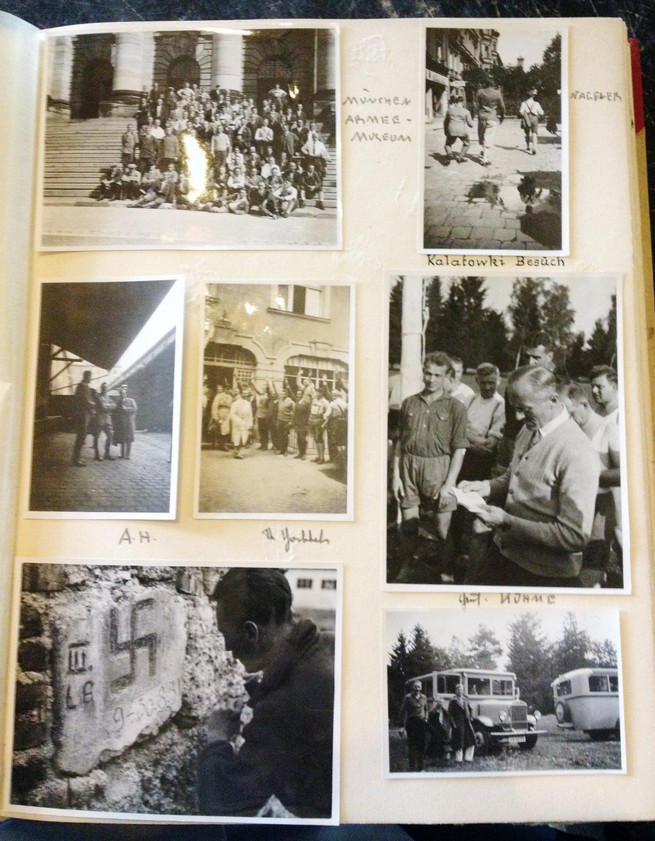

Sands had met Niklas in the course of his research, and Niklas urged him to speak to Horst von Wächter, the son of Otto; now 79, Horst occupies the family’s ancestral home, Schloss Hagenberg, in Austria. Sands described that meeting for the Financial Times in 2013—the chilly and threadbare public rooms; Horst’s personal warmth; and the photo albums with their family snapshots of beach vacations, Hitler and Himmler, mountain jaunts, and the Warsaw Ghetto. Unlike Niklas, Horst was hoping to recover some trace of good in his father. To that end, he shared with Sands a trove of family correspondence mouldering in boxes under the rafters. Sands cautioned that the outcome might not be the one Horst desired, and Horst accepted this. He agreed to give copies of the original materials to the Holocaust Museum, as he has done, and sent Sands a complete set for his own research and use.

Otto von Wächter had served during the war as governor of Galicia, answering to Hans Frank. He was responsible for creating the Krakow Ghetto and for implementing the Final Solution in the region he controlled. As the killing intensified, Hans Frank thanked Wächter for “making Lemberg a proud city.” With Germany’s defeat, in 1945, Wächter became a hunted man, sought by the Americans, the Poles, and the Russians. He hid for more than three years in the mountains, aided by Charlotte, then in April 1949 slipped into Italy, where he was given a new identity (and protection) by the notorious pro-Nazi Austrian bishop Alois Hudal. Hudal presided over the German national church in Rome, Santa Maria dell’Anima, not far from Piazza Navona, and had been instrumental in setting up one of the major ratlines. (In 1950, Adolf Eichmann would escape to Argentina with Hudal’s assistance.) Wächter had only a few months to enjoy Rome. He took a bit part in a movie, La Forza del Destino, based on the Verdi opera. He socialized. He planned his escape. But in July he suddenly took ill. “I’m a poor little Hümmchen today,” he wrote to Charlotte, “lying in bed with a fever. The day before yesterday was Saturday and an old comrade, who’s been very kind to me, invited me to Lake Albano.” His fever grew worse, his organs shut down. He was dead within days. Bishop Hudal was with him at the end.

What had happened to Wächter? Charlotte went to her grave believing that Otto had been murdered—poisoned—and spent her remaining years exploring various theories with friends and associates, which she helpfully preserved on tape. She had arrived in Rome too late to see her dying husband, but recalled his body appearing “completely black like wood, and burned.” Rome at the time was aswarm with ruthless characters maneuvering within a lattice of Cold War rivalry. The atmosphere was more like that of The Third Man than of Roman Holiday. Russians and Americans were active, whether to bring war criminals to justice or recruit them for other purposes. Nazi remnants had their own agendas, open or covert. For whatever reason—sympathy? self-interest? naivete?—powerful prelates within the Church had played an ignominious role throughout the war, and continued to play one afterward. Israelis, too, were on the scene—aggressively hunting for men like Wächter and sometimes exacting retribution.

And what about that “old comrade” he had visited at Lake Albano? Whose payroll was he on? In the podcast, John LeCarré, whose postwar service with British intelligence brought him into the heart of this shadowy world, offers an overview of the actors and motives. (“We were not all sweet,” he observes. As for retribution: “There was a lot of killing of that sort going on, and I would have to say I admired it.”) The forces at play—and possible clues to Otto’s fate—seep out from between the lines of the Wächter correspondence, which from the Rome period alone totals more than 300 pages. I won’t trespass unduly on the story related in The Ratline or in the book to follow. Wächter was a monstrous man. But there are good reasons for wondering whether something lay behind Wächter’s mysterious death besides the explanation given as the official cause: an illness picked up by swimming in the Tiber, which Wächter did every day. One way or another, swimming in polluted waters brought him down.

For many Americans, it has been tempting to see the Second World War as something that ended, with a hard stop. That was never true. The run-up to wars and the waging of wars get more attention from historians than the aftermath; the aftermath can be just as complicated and just as insidious, and it lasts longer. The sons of Wächter and Frank are embodiments of a war that never ended. In a vastly different way, so is the work of Philippe Sands.