For Kevin Wilson fans, the opening of his fourth novel, Now Is Not the Time to Panic, will feel familiar: A woman named Frankie Budge receives a call from a reporter asking about her role in a moral panic that spread from a tiny Tennessee town to the rest of America in the summer of 1996. The call sends Frankie reeling—“Oh shit, oh shit, oh shit, fuck, no in my head, a kind of spiraling madness … Because, I guess, I’d let myself think that no one would ever find out.” Not that she’s ever left that summer behind; she’s been replaying snippets of it in her head for the past 21 years. Now, for the first time, Frankie lets herself dive deep into memories of being 16, when she and her only friend, Zeke, made a cryptic piece of art that sparked all kinds of mayhem.

As idiosyncratic as that premise sounds, it’s a standard Wilsonian setup (or, one might say, obsession): An adult receives news that propels them back to a defining moment of their misfit youth. In much of his fiction, we’re brought to small-town Tennessee by narrators who were teens in the ’80s or ’90s. And, more often than not, the defining moment qualifies as traumatic. In The Family Fang (2011), the siblings Annie and Buster return to their childhood home to figure out how to revive their fizzling careers and process their pasts (as kids, they were constantly enlisted in their parents’ insane pieces of performance art). In Nothing to See Here (2019), the listless 28-year-old Lillian gets a letter from her high-school best friend, Madison, and we learn how she derailed Lillian’s once-promising future. In the short story “Biology,” Patrick, now an adult, learns that his eighth-grade biology teacher has died, and we’re thrown back to the time when Patrick was a pariah and the lonely Mr. Reynolds served as both a rescuer and a warning. In “Kennedy,” Jamie, now grown, recalls an 11th-grade classmate tormenting him and his only friend, Ben, in ever more horrifying ways.

To put it another way, Wilson looks at first glance like a poster boy for the trauma-plot trend that the New Yorker critic Parul Sehgal lamented in a much-cited essay this year. In the litany of recent stories about damaged pasts, she argued, the figure in the foreground tends to have the same profile: “Stalled, confusing to others, prone to sudden silences and jumpy responsiveness. Something gnaws at her, keeps her solitary and opaque, until there’s a sudden rip in her composure and her history comes spilling out, in confession or in flashback.” Instead of focusing on the future, Sehgal wrote, these stories direct us to the past (What happened to her?). Gone are “odd angularities of personality” and trajectories stuffed with intrigue, deepened by imagination, broadened by attention to the outer world.

But Wilson’s mission turns out to be outwitting the trauma-plot trap, and doing that with antic energy. In story after story, he takes what would seem like key ingredients for claustrophobia —damaged characters prone to rumination, flashbacks, and inertia—and whips up something utterly inventive and outward-looking. As if he’s never fully outgrown the hyper-self-consciousness and melodramatic aspirations of adolescence, Wilson’s fiction will have you laughing so much that you’re not prepared for the gut punch that follows.

Though many are loners, his characters are rarely going it alone; he playfully externalizes their fears and anxieties using off-the-rails plots (teens who spark a moral panic) and surreal elements (in Nothing to See Here, kids who combust when agitated). Wilson’s protagonists aren’t scratched records, doomed to replay past terrors for the rest of their lives. They are quirky, fleshed-out figures who seize on second chances to find purpose and connection—often through creative means. Now Is Not the Time to Panic is the heartfelt culmination of many years (and many pages) spent probing the tension between the urge to make a mark on the world and the costs of doing so—and the push-pull between art’s disorienting and generative powers.

The catalyst for all of this probing is Wilson’s own life as a writer. As an adult, he was diagnosed with Tourette’s syndrome, and he has spoken about writing as “the thing that saved” him from violent intrusive thoughts that led nowhere good—looping visions of “falling off of tall buildings, getting stabbed, catching on fire.” Putting these ideas on the page offered him a brief reprieve and some sense of control. During his childhood, before the unwanted thoughts had a label, reading served as a similar distraction. Many of his protagonists are made in the same mold, alert to the ways that imagination can hold them hostage and also allow them to order a world with room for them in it.

Now Is Not the Time to Panic, as Wilson has explained in interviews, is itself the product of one long-held looping thought that he wanted to bring to an imaginative end point. During college, he had a summer job mindlessly typing up a long policy manual, and he began inserting random phrases just to see if anyone would notice. One day, his friend—an artist whom he admired—suggested the words: “The edge is a shanty town filled with gold seekers. We are fugitives, and the law is skinny with hunger for us.”

The phrase, a “tossed-off little silly thing,” burned into Wilson’s brain and became a sort of mantra he used to calm himself when overwhelmed, even years afterward. He lent the words to Buster, the struggling writer in his first novel, The Family Fang, who recites them like “a prayer” as he tries to write another book after a long slump. Still not done with the phrase, a decade later Wilson has built an entire book around it.

In Now Is Not the Time to Panic, he hands the words to another writer figure—this time to chaotic ends. After Frankie learns that a reporter is looking into her past, we’re taken back to the summer of 1996, when a kid named Zeke moves to the “dinky little town” of Coalfield, Tennessee. Frankie—a repressed 16-year-old, well aware that she’s an oddball—is living with her single mother and triplet brothers. She and Zeke bond over having “dads who sucked” and creative aspirations (she’s writing a “weird girl detective novel”; he draws comics).

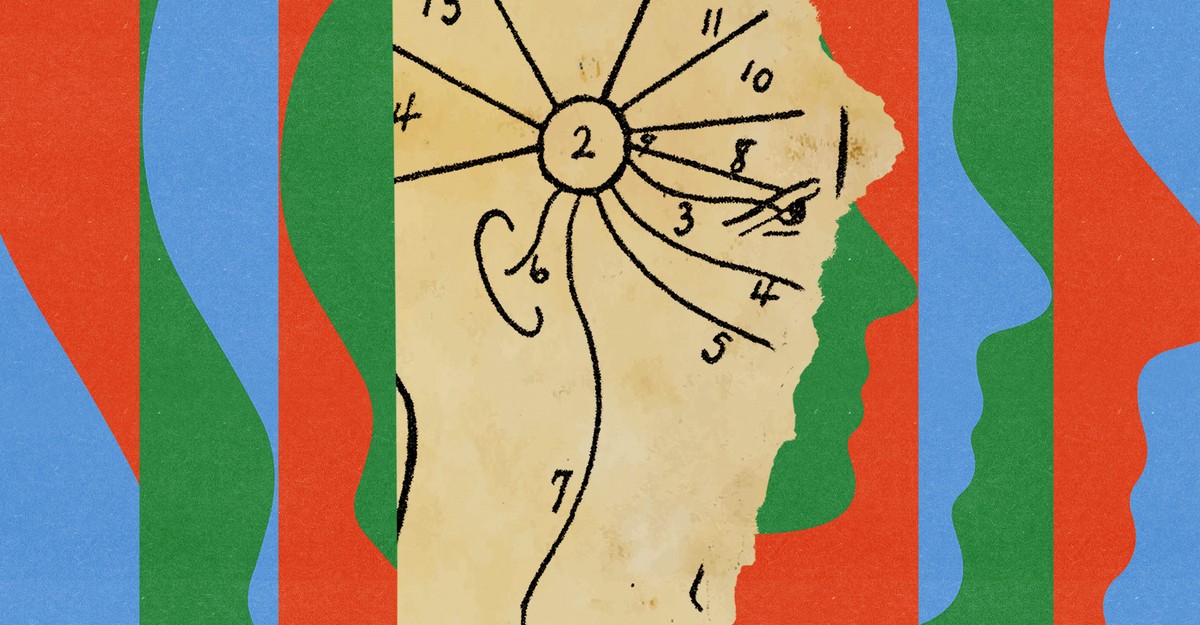

The two spend an unsupervised summer kissing (Zeke “tasted like celery, like rabbit food … I loved it”) and messing around with a copy machine stolen by Frankie’s brothers and stashed in their garage. They’re trying to make art—with very few reference points. “We didn’t know about Xerox art or Andy Warhol or anything like that. We thought we’d made it up,” Frankie recalls. One day, she scrawls the cryptic phrase (“The edge is a shantytown …” ) on a piece of paper, Zeke adds a strange illustration, and they go on to post copies of their unsigned creation all over town like they’re on some sort of spy mission. Soon the poster spawns copycats and conspiracy theories, and even costs lives in what becomes known as the Coalfield Panic. A terrified Zeke leaves town, and Frankie, devastated by his disappearance, keeps their role a secret.

But hard though she tries, Frankie can’t leave this summer behind. As her teens give way to her 20s, the Coalfield Panic acquires the status of “one of the weirdest mysteries in American pop culture,” generating fascination well beyond her small town. It becomes the subject of Pulitzer Prize–winning reporting, episodes of Unsolved Mysteries, and even a Saturday Night Live skit “where it turned out that Harrison Ford was putting up the posters, though he blamed it on a one-armed man.” The band the Flaming Lips releases a 27-song album called Gold-Seekers in the Shantytown. The panic inspires emo-band names and Urban Outfitters posters and a whole Bathing Ape clothing line.

Wilson’s witty depiction of a country obsessed with this bizarre contagion—and determined to cash in on it—doubles as a compelling portrait of anxiety. Frankie’s fear of being exposed is never far below the surface, thanks to an ambient culture that operates like an intrusive thought, constantly reminding her of that period in 1996. That the Frankie we meet in 2017—though now a successful young-adult novelist and mother to an adorable kid—still feels tethered to that summer is hardly a surprise. But in Wilson’s telling, she is not simply ensnared. Whenever Frankie feels adrift, she makes a copy of the poster (yep, she’s saved the original) and hangs it up, in order to “know, in that moment, that my life is real.” She feels moored, not immured, “because there’s a line from this moment all the way back to that summer, when I was sixteen, when the whole world opened up and I walked through it.”

As teens, Frankie and Zeke naively enacted lofty debates about art, which Wilson captures in pitch-perfect ways: What kind of cultural exposure does an aspiring artist need? (Frankie, feeling cut off in Coalfield, is desperate for guidance on “what other people thought was good or what was important.”) Who bears responsibility for an artwork once it has met air? Is it the artwork’s quality or its impact that matters? But Wilson is more interested in how art and imagination operate on his characters—and by extension, himself. Above all, he’s alert to their liberating potential. Like the offbeat figures he writes about, he is caught up in a repetitive cycle of processing difficult events on the page: His fiction is like a set of nesting dolls, the themes and preoccupations of one story feeding into the next, alike in their contours but wonderfully unique in their particulars. If that sounds like a writer in a rut, go read Wilson’s books. You’ll discover one-of-a-kind worlds opening up.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.