Loading the Elevenlabs Text to Speech AudioNative Player...

Accounting for the innumerable ways that a mild-mannered businessman is distinct from a best-selling author, I always felt that my father had more than a few things in common with Kurt Vonnegut.

Both were Midwesterners (Vonnegut was from Indiana, my father from Ohio). Each had a trenchant sense of humor (Vonnegut’s won him fortune and glory, my father’s won him a few laughs around the homestead), and each expressed extreme dubiousness about American participation in forever wars—the sort of skepticism of feckless engagements that only those who served in uniform, as both my father and Vonnegut had, can muster. (Of course, Vonnegut’s experience in the Second World War became the basis for his great novel Slaughterhouse-Five; my father had a rather less notable eight-year career as an Air Force officer at the time of the Cold War.)

But the biggest thing that my father shared with Kurt Vonnegut was a weakness for using the telephone to locate long-lost friends.

“I have this disease late at night sometimes, involving alcohol and the telephone,” Vonnegut writes early in Slaughterhouse-Five. “I get drunk, and I drive my wife away with a breath like mustard gas and roses. And then, speaking gravely and elegantly into the telephone, I ask the telephone operators to connect me with this friend or that one, from whom I have not heard in years.”

Reading that line as a teenager, eager to find overlaps between my father and my favorite author, I was so struck by the similarity that I rushed to my mother to repeat the passage. “That sounds like Dad,” she told me—and it did, except for the alcohol part. (Unlike Vonnegut, my father was a teetotaler who had probably not had a beer since his days in the military.) But the impulse to find old acquaintances? In that, my father and Kurt were two of a kind. Being a bit of a loner, my father let himself fall out of touch with high-school pals, college chums, and even his brothers-in-arms from Officer Training School. But, every few years, he evidently found himself overcome with the urge to reconnect.

Another key difference: When my father decided that he wanted to find a voice from the past, it fell to my mother to get down to the practical business of the finding.

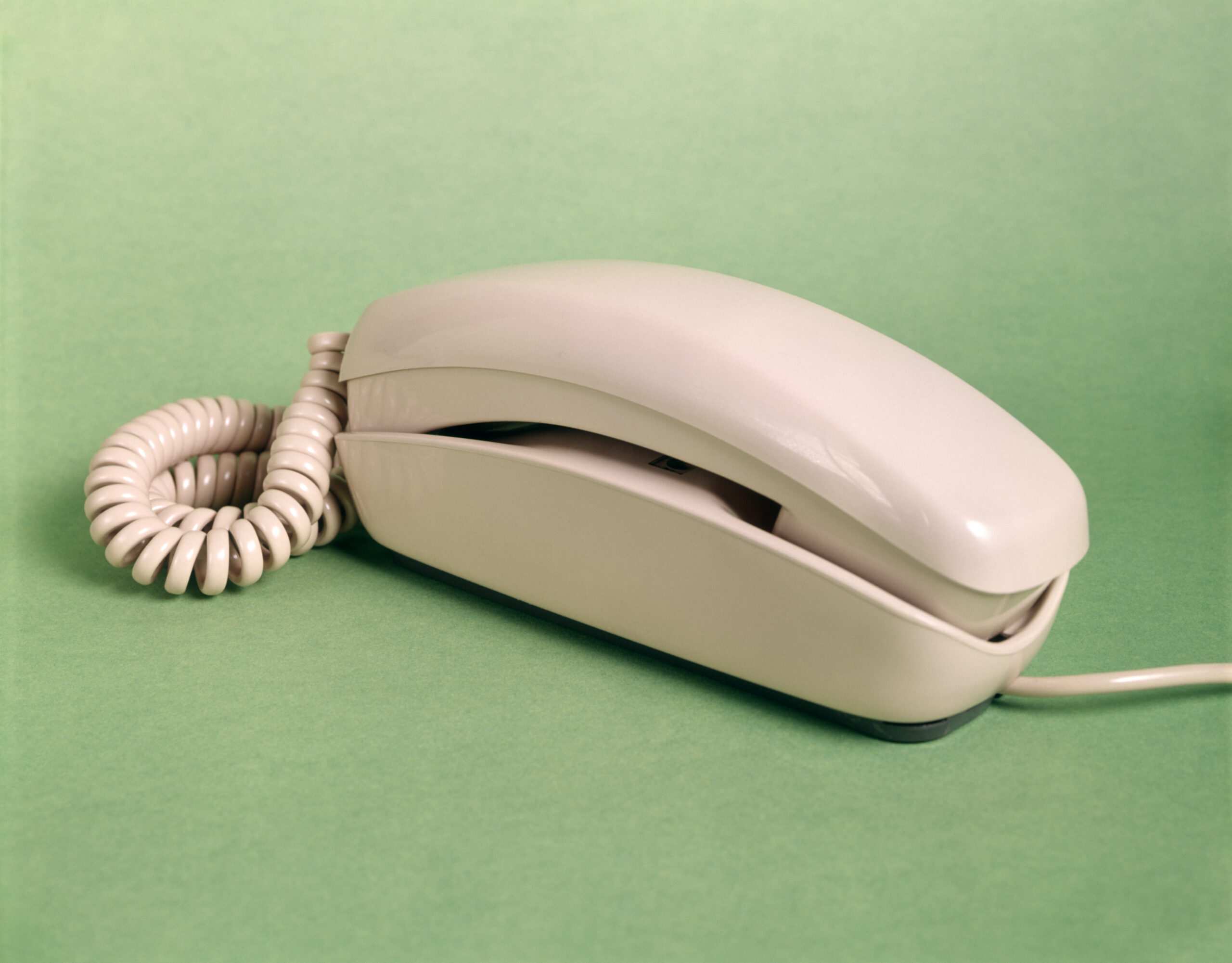

It was my mother who maintained the family address books, and in truth, it was usually she who dialed the multiple old numbers listed under a given name and, if someone picked up, politely inquired whether she had reached the intended person. Given how frequently people changed phone numbers in the days of landlines—essentially, each time someone moved any distance—these calls were really the equivalent of cold-calling. They took nerve, which my mother had. She became an expert practitioner in using directory assistance, whereby, if she had a credible guess as to the present location of the sought-after ex-friend, she could check to see if they had a listed number. Sometimes they did; often they did not. Such was the nature of the chase.

Entire Saturday afternoons would drift away in all this dialing and redialing. At some point, my father’s interest would flag—inevitably, he would wander from his home office, where these phone searches would be conducted, to watch the ball game on TV—but my mother would keep at it. She knew that the thrill of trying to find someone was in the pursuit: the endless calls, the false leads, the fleeting moment of hope between the last ring and a voice picking up the receiver on the other end.

From my perspective, there was a real air of mystery in my parents’ efforts to find people with whom they had not been in contact for years or sometimes decades. This was the 1990s, and the pre-social media internet offered next to no insight into what a relatively anonymous person might be doing with his life. Thus, a phone call with someone from the past carried with it the promise of learning about all the things that had happened to them, good or bad, since the last phone call.

In my recollection, my mother failed more than she succeeded in locating whoever my father fleetingly wished to reach, but those occasions that met with success were genuinely exciting. So-and-so moved to Florida; so-and-so took a job in retail. It was an excitement I would not know again until I became a reporter. I was well prepared to try to find an elusive interview subject needed for a story—to “work the phones”—because I had seen my mother do just the same thing.

I like to think that when she reached the old friend she and my father had been looking for, the person on the other end was happy to hear from her if for no other reason that they knew how much effort it would have taken; it wasn’t as simple as messaging someone on Facebook. These days, my father’s efforts to reconnect with this or that person would be far easier to satisfy, but in our society’s all-too-easy accessibility, I think we have lost a proper sense of the ineffable mystery of human affairs. Perhaps it is not for the good that we document our lives online for anyone, even pals from long ago, to find; maybe it would be better if we saved up our joys, our sorrows, our changes in location and career for that phantom phone call from a long-ago acquaintance out of the blue.