Loading the Elevenlabs Text to Speech AudioNative Player...

The other day I pondered a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore. It was The New York Times of almost exactly one hundred years ago, October 2, 1925. On page 32, the headline: “Big Power System Planned in the South: Three Groups To Ask Right to Develop Tennessee River and Muscle Shoals: World’s Largest Plant.”

The story detailed the plan for development deep in Dixie. One investor said the area could produce “one fifth of the total hydroelectric production of the country.”

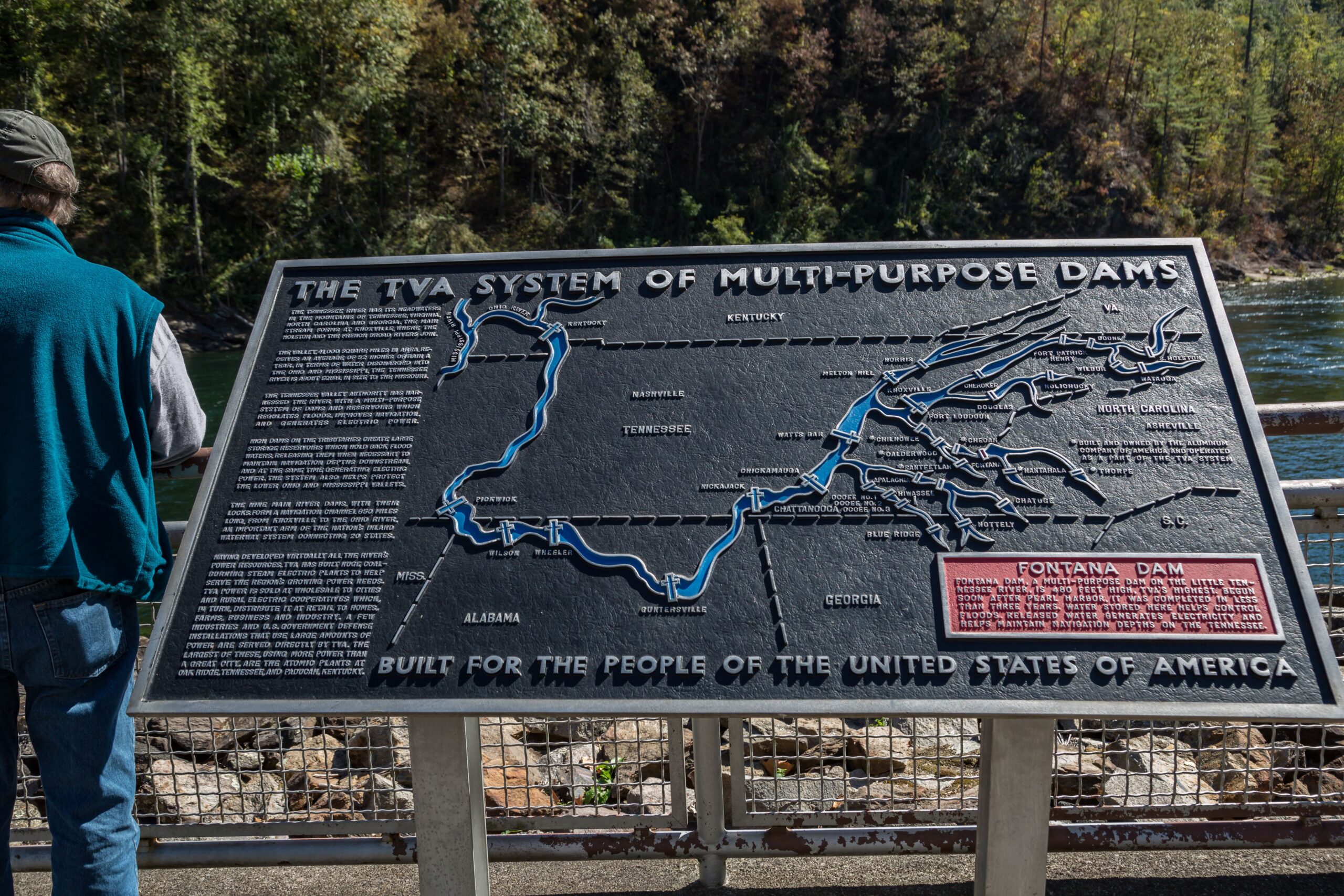

But wait! Everyone mindful of American history knows that “power system” + “Tennessee River” = Tennessee Valley Authority, the giant public operation, established in 1933 during the New Deal, stretching across Tennessee and parts of six adjoining states.

History buffs also know that TVA’s status as a government-run entity has been sacrosanct. After all, in 1964, Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater mused about selling off TVA, and he was clobbered in the November election, losing 44 states, including the Volunteer State.

So with apologies to Edgar Allan Poe, it has seemed that the idea of privatizing TVA would forever be met with a dark and stark nevermore.

Yet as that old Times story indicates, a century ago, in the cheery days before the 1929 Crash and the subsequent Depression, the idea of private development was ripe. During the Great War, the U.S. Army had developed a nitrate factory, for munitions, at Muscle Shoals, Alabama. In 1921, the towering industrialist Henry Ford had proposed to buy out the feds and further develop the area; the pitch persisted all through the Roaring Twenties.

Yet the entrepreneurs, potent as they were, found themselves pitted against another formidable force: the view that the public should own the means of power production. The leading proponent of state-owned power was Sen. George W. Norris of Nebraska. Norris, who served in the Senate for 30 years and in the House for a decade prior to that, was a Republican, but was also a progressive—which is to say, he was to the left of many Democrats in Congress.

Much of his autobiography, Fighting Liberal, is devoted to the power issue in general, and to TVA in particular. He recalls ardent private-sector enthusiasm in the 1920s: “the belief that in the vicinity of Muscle Shoals would be one of the largest cities in the world.” He added, “Men told me they expected a city there which would outstrip New York in population. Men of wealth and power shared this belief.”

But Norris didn’t agree. He studied the issue, conducted hearings, visited the area—where he observed that the locals were in favor of the project—and yet he, as a Yankee, concluded that a publicly-owned facility could be “operated at much less expense.”

Today, such faith in the efficacy of bureaucracy might strike anyone this side of Zohran Mamdani as naive. Yet in Norris’ defense, a century ago, the world hadn’t heard much about collectivization and Five Year Plans—and what it did hear was often Duranty-ized propaganda.

So, all through the ’20s, Norris used his influence as part of the Republican majority—he was variously chairman of the Senate Agriculture and Judiciary Committees—to block Ford and other would-be tycoon-developers.

Indeed, Norris managed to rally a bipartisan majority in Congress in support of a national public venture at Muscle Shoals. But President Calvin Coolidge pocket-vetoed the bill in 1928. Three years later, President Herbert Hoover outright vetoed it, stating the free-enterprise case against federal ownership:

The real development of the resources and the industries of the Tennessee Valley can only be accomplished by the people in that valley themselves. Muscle Shoals can only be administered by the people upon the ground, responsible to their own communities, directing them solely for the benefit of their communities and not for purposes of pursuit of social theories or national politics. Any other course deprives them of liberty.

Yet by then, Hoover and the free-enterprise faith were drowning in the Depression.

In 1932, Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt campaigned for the White House declaring his opposition to Hooverism and his support for Norris-ism: “The question of power, of electrical development and distribution, is primarily a national problem.” Having embraced an activist role for the federal government, Roosevelt further pledged to combat the “many selfish interests in control of light and power industries.”

That November, FDR defeated Hoover by 18 points, giving his New Deal a clear mandate, including for nationalized public power.

The following year: TVA. The massive project, built without much regard for environmental impact statements, proved itself a dynamo, driving not just prosperity for the area, but security for the nation. The major reason the Manhattan Project chose Oak Ridge, Tennessee, for its uranium-enriching plant was its proximity to the abundant hydropower generated by TVA dams.

The question unasked in those days: Could Henry Ford & Co. have built the same dams and provided the same power? Maybe cheaper, faster, better? Could, perhaps, private capital have made Muscle Shoals into Manhattan, as the capitalists had envisioned? We’ll never know.

But we do know that there’s a Norris Dam in Tennessee. So the Nebraskan has his legacy in TVA.

We also know that the Power Question continued to radiate, one of the hottest topics of the interwar era. Even as the New Dealers proceeded with the public TVA, they targeted private utilities. In 1935, the administration teamed with Rep. Sam Rayburn, chairman of the House Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee, to advance the Public Utility Holding Company Act. PUHCA included an ominously named “death sentence” provision for then-prevalent holding companies.

No wonder the battle was a burner. In FDR, the New Deal Years, 1933-1937, historian Kenneth S. Davis records the drama of PUHCA:

There followed five bitter winter weeks during which the utilities, with Wendell Willkie of Commonwealth and Southern as principal spokesman, raised such hue and cry as had not been raised against a single measure, perhaps, since Stephen Douglas’s Kansas-Nebraska bill was before Congress in 1854.

Roosevelt won on Capitol Hill, and yet along the way, a Republican star was born. That would be the folksy but silver-tongued Wendell Willkie. Interestingly, Willkie had been Democrat, never previously elected to anything. Yet the PUHCA pandemonium made him famous; Republicans, desperate for fresh talent, drafted him to be their 1940 presidential nominee.

Willkie lost that election, and yet over the rest of the 20th century, he won the argument; most Americans came to conclude that public ownership of utilities—or public ownership of any sort of economic enterprise—was not such a good idea. Whether or not we know the exact economic jargon, we intuit the concept of regulatory capture.

That is, the idea that one interest or another will use political pull to seize control of a public enterprise, twisting it toward its own narrow ends. For instance, in the case of the public schools, it’s the unionized employees atop the commanding heights; students are an afterthought, parents are pushed aside, and for those interested in proficient test scores—fuhgeddaboutit.

As for utilities, the capturers have often been environmentalists, turning power companies into slush funds for green experimentation. Here, the TVA was a pioneer. Back in 1977, President Jimmy Carter appointed a green, S. David Freeman, fresh from a stint as a limits-to-growth-guru at the Ford Foundation, to head TVA. Whereupon Freeman, joining an up-and-coming lawmaker named Al Gore, set about greening. Years later, an admirer eulogized Freeman: “No single human can claim a greater impact in shaping progressive energy policy.” Of course, Malthusianism is not what Sen. Norris had in mind, but that’s the thing about capture: the conquered can be carried off anywhere.

Yet today, a century after those capitalists sought to transform Muscle Shoals into Manhattan, we have a president who’s a conqueror of a much different kind. In his developer days, he transformed his home town into a more glittering, golden-hued destination.

To be sure, Donald Trump is no longer welcome in Mamdani-ized Manhattan, and so he has aimed his art-of-the-developer magic elsewhere, at Oman, at Greenland, even at the White House itself.

And at TVA, too. In 2018, the then-45th president wrote in his budget proposal,

The private sector is best suited to own and operate electricity transmission assets. Eliminating the federal government’s own role in owning and operating transmission assets encourages a more efficient allocation of economic resources and mitigates unnecessary risk to taxpayers.

Upholding Norrisism, then-Sen. Lamar Alexander, Republican of Tennessee, dismissed Trump’s message as “a loony idea.”

Yet now Alexander is gone and Trump is back. Rumor has it that 47 wants to sell off TVA. After all, its value has been estimated at $58 billion, so a sale would dent the deficit. Indeed, if the power plants became more productive assets in private hands, they would then generate fresh tax revenue.

But how would such a privatization fit with Trump’s recent record of having Uncle Sam take a “golden share” of U.S. Steel, Intel, and maybe that rare-earth mining company? Best to let the president speak for himself—he always does. In the meantime, just know that Trump loves deals.

So now the forgotten lore is being remembered. We’re back to the days before the New Deal, when confident developers could tout their grand plans to buy up, and build out, the Bible Belt.

At the same time, if Russ Vought, Elon Musk, and the DOGE Boys can look at TVA and see another bit of Big Government to shut down, they’ll be happy. So paleo meets techno, a harmonic coalitional convergence.

Back to Poe: I stood there, wondering, fearing, doubting, dreaming: Maybe the old nevermore is not, in fact, with us anymore. Maybe, after nearly a century of bureaucracy, what we’re seeing now is a thing newer than the New Deal.