Loading the Elevenlabs Text to Speech AudioNative Player...

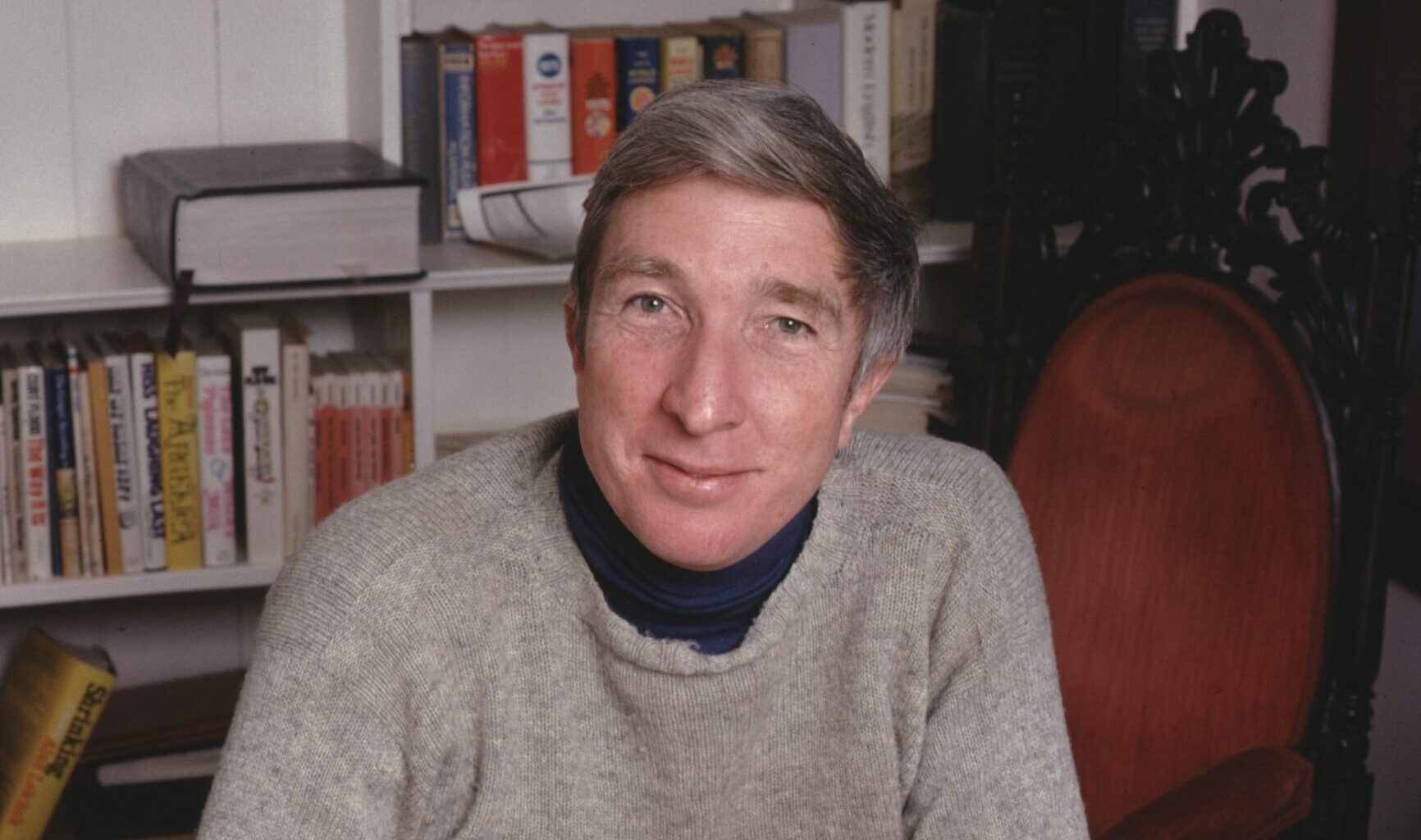

Selected Letters of John Updike

Edited by James Schiff

Knopf, 912 pages, $55.00

At one point in “The Music School,” the loveliest and most evocative of all of his short stories, John Updike has his narrator describe the bimonthly practice of corporate confession at his country church—presumably a Lutheran church, the denomination in which the author was reared. There, the congregants kneel while listening to the pastor intone the words: “Beloved in the Lord! Let us draw near with a true heart and confess our sins unto God, our Father.” The narrator observes: “There was a kind of accompanying music in the noise of the awkward fat Germanic bodies fitting themselves, scraping and grunting, into the backwards-kneeling position.”

After the confession, the congregants are called to the altar to receive the bread and wine. “Above their closed lips their eyes held a watery look of pleading to be rescued from the depths of this mystery,” says the narrator, on whom this routine has left a lasting inclination towards self-revelation.

“My psychiatrist wonders why I need to humiliate myself,” he says. “It is the habit, I suppose, of confession.”

To judge on the evidence, Updike, who was born in 1932 and died in 2009, shared in this compulsion toward confession. Few American authors of the past century churned out as many words. Even peers who matched or exceeded Updike’s productivity when it came to novels, such as Philip Roth, could not keep pace when factoring in the numerous other modes in which he regularly put pen to paper: short stories, poems, book reviews, essays, a play, a memoir, and even five books for children. Multiple books appeared after his death, including a final volume of short stories, My Father’s Tears.

It should come as no surprise, then, that Updike was as expansive, candid, and prolix in his personal correspondence as he was in his writing for publication and for pay. The superb, revelatory Selected Letters of John Updike gives an indication of the eagerness with which Updike wrote to friends, family members, both his wives, countless editors, and even the occasional critic. By the same token, the stuff and substance of these letters is much like that of his much-honored fiction, including “The Music School”: ordinary life, up to and including churchgoing. “Updike was able to bestow vibrancy and meaning upon that which would otherwise seem ordinary, so that it resonates and hums,” writes James Schiff, the editor of the present volume. “In so doing, he offers us a new way of seeing and knowing our daily lives.” We find here that Updike was that rarest of things: a writer who wrote much the same in private as he did in public.

Schiff presents Updike’s correspondence in chronological order, which gives the reader the pleasure of tracking the development of his intellect and the attainment of his aims, professional (in the form of contributions to the New Yorker) and personal (expressed most vividly in his marriage to his first wife, the former Mary Pennington, and the birth of their four children). Some of the earliest correspondence gathered here reflects Updike’s youthful drive to become a cartoonist, though even in these examples, his gift with words shines through most clearly. In a 1947 fan letter to the cartoonist Milton Caniff, Updike takes an entire paragraph to pay an elaborately structured compliment. “For a long time, I was under the impression that Terry and the Pirates was the best comic strip in the United States,” he writes, noting, with dismay, Caniff’s decision to “desert” the strip in favor of a new venture, Steve Canyon. “Apprehensively I subscribed to the paper that carried Steve Canyon and waited for results. It didn’t take me long to discover that Steve Canyon was now the best comic strip in the United States.” He then asks for a piece of art—an original strip, perhaps, or a sketch of the title character—to “cover a blank wall in my bedroom.” The following year, he uses the same language—about the need to acquire original art to fill a blank wall—in a letter to Harold Gray of Little Orphan Annie. “Whatever I get will be appreciated, framed, and hung,” he writes.

By 1949, though, Updike’s ambition had grown from art collector to potential art contributor. “I would like some information on those little filler drawings you publish and, I presume, buy,” Updike wrote “to the editors” at the New Yorker. “What size should they be? Mounted or not? Are there any preferences as to subject matter, weight of cardboard, and technique?” Updike would never forsake his belief in the almost divinely ordained superiority of the New Yorker, though the object of his ambitions in the magazine gradually shifted from images to words. A 1954 Western Union telegram to his father commemorates the sale of his first poem to the magazine, “Duet with Muffled Brake Drums.” “New Yorker buying Rolls Royce poem future things must go to Mrs. White Whopee—LOVE,” Updike writes, referring to New Yorker editor Katharine White (to whom many future missives are addressed). This telegram is to his father, but Updike plainly derived much of his drive from his mother, an aspiring writer who later achieved publication herself.

“Your own letters, besides being embarrassingly more numerous than mine, are much more literate,” Updike writes to his mother in 1951, while he is still a student at Harvard College. “Your serialized commentary of Styron’s book loses almost none of its charm and perception through the fact that I have not read a word of Lie Down in Darkness.” Many of the letters here have a similarly confident, even peppy tone, including a prediction of temporal success and spiritual fulfillment in the life he hopes to share with his wife-to-be, Mary. “It is my faith that eventually I will make it, that before either of us become too weak to bear poverty, or near-poverty, I will be reasonably prosperous, some sort of ornament to the literature of my age,” Updike writes to Mary in 1952. “How long this will take, I don’t know. Until I am thirty? Perhaps. But we are young, and strong, and must learn to be patient. If I make it before, that is just so much jam on the sandwich.” With love letters so well written, could the recipient ever doubt their sender’s promises?

Updike is similarly insistent even in his earliest interactions with editors. In 1954, after signing a much sought-after “first reading” contract with the New Yorker, he sheepishly (but strangely confidently) confesses that he had, prior to receiving and executing the document, already broken it by submitting a pair of poems elsewhere. “In the extremely unlikely event of a double acceptance on either end, I will, of course, honor yours,” he writes. To the Harper & Brothers editor Elizabeth Lawrence, who shepherded his first book of poems, The Carpentered Hen, into print, he assesses the physical properties of the final book in a letter from 1958: “The picture you used of me was a surprising choice but I appreciate, what I didn’t before, the humor of a black sling chair set out in the bushes, as it were.” Around the same time, he poses a question to Stewart “Sandy” Richardson, an editor at Knopf, which is to publish his first novel, The Poorhouse Fair, and all of his major subsequent books: “Could it be written into the contract that the dust jacket must be approved by me? Or is this understood?”

As Schiff promises, Updike’s letters commemorate and valorize everyday existence with as much vigor as his fiction. Consider this description to his parents of the house that he and Mary purchased for $18,500 in Ipswich, Massachusetts, in 1958. “There are 14 rooms, all but two of them the size of closets, but good for stashing children in,” he writes in 1958, the year of those first consequential publications. Other amenities: “Walking distance to schools, churches, stores, movie palaces, river side, etc.” He writes of having, upon completing this purchase, “that same feathery scared feeling as when you’re having a baby or getting married”—his terrain, after all.

Then come the years of abundance, including the arrival of the first novel in his saga of American life as perceived through the eyes of one Rabbit Angstrom, Rabbit Run. Yet Updike continues to balance the two kingdoms of his own consciousness: In one letter, he leans on Alfred A. Knopf himself to make “one more change” to the novel (“This is eight lines for six; the extra two will be made up in the next paragraph. Delete from ‘They walk as slowly . . . chokes the thought’”), and in another, he begs the indulgence of his then-father-in-law, a Unitarian minister who evidently had expected to be the one to baptize his grandchildren, rather than the minister his son-in-law had chosen out of expediency (“It was just that their pagan state nagged me”). He tells the Knopf editor Judith Jones about the outlines of his famous novel Couples (“[It] deals with the interactions of a not very distinguished group of post-war couples, centering upon the infidelities of a small contractor called Piet Hanema”), and he answers a pair of nasty missives from Lillian Ross, returning fire with fire (“I am astonished by the reserve of dislike you seem to have built up against me during the same years when I was innocently admiring your too-infrequent Profiles and your brilliant sequence of Spencer Fifield stories, for which, comically enough, I seem to have composed a little puff used in ads”).

There’s a slightly sickening quality to some letters to the sought-after Martha, and a sometimes uncharitable tone to some to the exiled Mary: In the aftermath of another of his affairs, he writes to Mary, “I have felt there was a degree of female warmth you were withholding, and in that sense have felt you as second best.”

Updike evidently had sufficient reserves of mental organization to balance his then-convoluted personal life with his booming career, represented in this letter to the Knopf president and chairman amid the transition from Mary to Martha: “Who runs Vintage now, and would there be any possibility of them printing a companion volume to the Olinger stories, a collection of Maples stories—about twenty, covering twenty years of a mythical marriage?” Schiff rightly praises Updike’s “remarkable ability to compartmentalize,” a quality that emerges from the varied nature of the letters on offer here.

What else? In 1983, to his mother, Updike notes that “winning the Pulitzer Prize is more work than you might think,” and in 1987, to the Knopf editor Jones, he proposes a $15,000 advance for a memoir, what became Self-Consciousness, to help him better support his mother, then in her 80s. In a letter unexpectedly addressed to the warden at San Quentin Prison, he attempts to fend off a prisoner called Richard Updike who seems to have been harassing him, and, distressingly, he declines a fee of $30,000, plus expenses, to go golfing with Clint Eastwood or Jack Nicholson for what sounds like an easy 3,000-word piece in Travel & Leisure Golf in the late ’90s. In 2000, he castigates the New York Times book critic Michiko Kakutani for an error he says she made in her review of Gertrude and Claudius.

These later letters, as Schiff notes, were “weighted more toward the professional,” though they are valuable for painting a portrait of a literary eminence plying his trade and managing his affairs. Even so, Updike was still capable of great thoughtfulness and eloquence, as in a 2008 letter to a United Church of Canada minister in which he takes issue with the then-fashionable atheism of Christopher Hitchens and his kind. “From the defensible position that there is no God he seems to have moved to the false claim that religion has done more harm than good down the ages,” Updike writes. “It is hard to think of humanity and human organization without it. And the great killers of the twentieth century—Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot—all did it without any theistic rationale.”

These words brought me back to “The Music School,” and its linking of a religious impulse to the confessional impulse. In 1996, promoting his great novel In the Beauty of the Lilies on Charlie Rose’s interview show, Updike was asked what religion had meant to him. Without hesitating, he said it gave him courage. “In other words, don’t play it safe,” Updike said then. “Go for it. Tell the truth at all costs. The Lord knows the truth, so why shouldn’t the reader know the truth?” Here, he tells it as he sees it, letter after letter after letter.