Loading the Elevenlabs Text to Speech AudioNative Player...

As the term of the Chilean president Gabriel Boric winds to a close, the candidates hoping to succeed him are putting their campaigns in motion. In Chile, currently dominated by a left-wing coalition led by Boric’s Frente Amplio party of social democrats, the political winds have shifted significantly—the vital energy is now on the right.

Boric and his social democrats, elected on the back of the estallido social—the “social outbreak,” a major wave of protests and civic unrest—have failed in their goal to fundamentally transform the country. The Chilean left suffered a humiliating defeat when their proposed new constitution, intended to replace the Constitution of 1980 put in place by Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, was decisively rejected by voters. (The situation became humorous when a second constitution, this time drawn up by the right, was also rejected in a popular referendum, although by a significantly smaller margin.) Boric, once the shining star of the young Latin American left, is now an exhausted political figure, as the region’s youth turn rightwards in concert with much of the world.

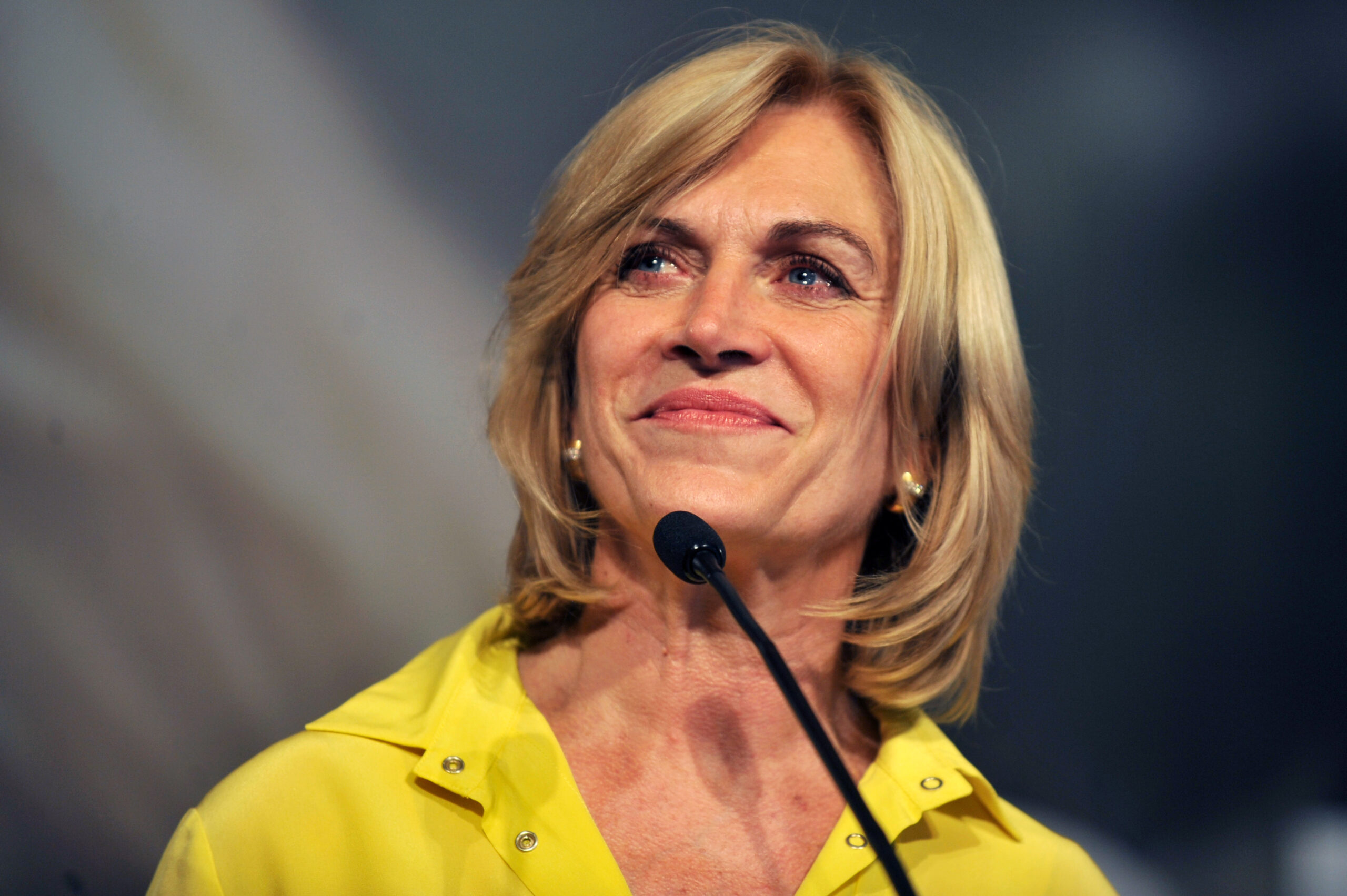

Aware of the threat to their political position, the Chilean left is pinning their hopes on a unity candidate to carry the banner in this year’s November presidential election. The various candidates for the Chilean communists, social democrats, progressives, and the green movement have entered a binding primary that will go to the polls in June, allowing the coalition to solidify around a single presidential aspirant for the general election. At the moment, that candidate looks most likely to be Carolina Tohá, who was the first female mayor of the Chilean capital city of Santiago and until recently served as the minister of the interior under Boric.

The candidates on the Chilean right, in contrast, are hungry to capitalize on the new national mood, and no one is eager to potentially bring their presidential ambitions to a premature end by participating in a primary—they’d rather enter the general election directly, even at the risk of vote splitting. The center-right candidate, Evelyn Matthei, currently holds the overall presidential polling lead, with the populist right wing vote divided between traditional left-wing bogeyman José Antonio Kast of the Chilean Republican Party and rising star Johannes Kaiser of the National Libertarian Party, who alternate between second and third place in the polls.

Matthei, the oldest candidate in the race, represents the forces of mainstream Chilean conservatism. Once a firm supporter of Pinochet’s regime—a political stance that in recent years has become far more controversial in contemporary Chile—she has tacked steadily towards the center, disavowing both her prior defense of the dictatorship of her youth and the hardline social conservatism of the traditionalist Chilean right (she has expressed support for same-sex marriage and liberalization of abortion law, positions anathema to the still-powerful Christian right). Her service as a labor minister and also as mayor of Providencia, one of Santiago’s wealthiest communes, has allowed her to cultivate an image of competence and pragmatism that appeals to Chilean business interests, and she has the potential to appeal to young urban professionals who have grown wary of the social democrats but dislike the policies and personalities of the populist right.

But while Matthei currently holds the lead in presidential polling, her biggest obstacle will come not from the left but from her right flank. The combined vote share of populist right-wing candidates José Antonio Kast, a firebrand social conservative who lost to Boric in 2021, and Johannes Kaiser, the Chilean echo of Javier Milei, is consistently larger than her own base of support.

Kast, who is viewed as something of a Trumpian figure among the Chilean left, continues to draw from a loyal base that yearns for a more aggressive rollback of Boric-era reforms and a clampdown on migration and crime. His Republican Party, founded in 2020, has become the dominant right-wing party in Chile, pushing Kast into competition for the presidency in 2021. A hardline social conservative, Kast draws especially strong support from the growing population of Chilean evangelical Christians, who appreciate his iron opposition to same-sex marriage and abortion. He is also hoping to capitalize on Chilean frustrations with the soft-on-crime, left-wing approach by running a law-and-order campaign, while also promising a liberalization of the economy to strengthen Chile’s economic growth.

That youthful energy on the right, however, is being captured by a new force in Chilean politics: the national libertarian movement. The success of President Javier Milei, who is the manifestation of this political tendency in neighboring Argentina, has given a major boost to the aspirations of like-minded politicians in Latin America. In Chile the standard bearer for this novel right-wing movement is a politician with the striking Teutonic name of Johannes Maximilian Kaiser Barents-von Hohenhagen, a YouTuber and social media maverick turned politician who has taken a surprise leap in the presidential polls.

Originally a proponent of José Antonio Kast and a politician for the Republican Party, Kaiser broke from his compatriots by voting against the 2023 constitution drawn up by the right. Kaiser has criticized Kast and the Republicans for being too statist. “We don’t believe in the state as the guide of public morals,” he said in an interview with the Chilean online publication Emol. Kaiser’s appeal is much less oriented around social conservatism—although he is an Orthodox Christian convert—than around opposition to the Chilean state apparatus: He proposes a radical reduction of taxes and regulations, major cuts to the government budget, and, most controversially, the privatization of Chilean state-controlled mining enterprises. Like Milei, his appeal is particularly strong with younger men, many of whom do not consider themselves conservative or right-wing.

The factionalism of the Chilean right means that Matthei, Kast, and Kaiser are essentially wagering on taking second place in the first round of the presidential election this November. Whatever right-wing candidate came in second would then proceed to, and almost certainly be favored in, the second-round runoff election against the left-wing candidate. In this election, second really may be the best—and whichever candidate achieves it could set the course of the Chilean right for years to come.