Loading the Elevenlabs Text to Speech AudioNative Player...

Senator John McCain delivered a video statement to the Republican National Convention in St. Paul, Minnesota on August 31, 2008. The presumptive presidential nominee told RNC-goers that the convention agenda would be reduced to only most essential party business as Hurricane Gustav neared the Gulf Coast. “We take off our Republican hats and put on our American hats,” McCain told his fellow Republicans in the video. As the RNC turned its attention to Hurricane Gustav, the Washington Post reporter Dan Balz wrote that, for many Americans, “the hurricane in question is still called Katrina.”

Even Bush acknowledged his Katrina response left his presidency beyond recovery. In his presidential memoir Decision Points, Bush confessed that Katrina “cast a cloud over my second term”—a metaphor as unfortunate as the administration’s response, yet quintessentially Bushian. Top members of President Bush’s staff agreed, but chose to shy away from atmospheric figures of speech. “It left an indelible stain on his presidency,” wrote Scott McClellan, Bush’s White House press secretary, in his postmortem of the Bush presidency, What Happened.

Ten years after the storm, Douglas Brinkley wrote for Vanity Fair that Hurricane Katrina was the “Flood That Sank George W. Bush”. A presidency can withstand incompetence or failed messaging strategies, but they rarely survive both. The mismanagement and poor messaging that doomed Bush’s presidency were nowhere more apparent than in the response to Katrina. Throughout the crisis, the Bush administration lacked the initiative and ingenuity to boldly assert the president's powers under federal statutes and Constitutional principles. Its cowardice bled over into communications, where strategies from Bush’s inner circle damaged the president’s image almost as much as his own words and actions. Bush and his administration were unwilling or unable to do what was necessary to minimize human tragedy.

No natural disaster in U.S. history compares to the damage wrought by Katrina. Hurricane-force winds extended 103 miles from the storm’s center, causing a disaster area that spanned 93,000 square miles—the size of Great Britain. Katrina claimed 1,000 lives, caused more than $100 billion in damage, and consumed an estimated 300,000 homes. The storm displaced nearly 800,000 people and caused the largest internal migration since the Dust Bowl migration of the 1930s. Regardless of the government’s response, Katrina would exact its toll on American blood and treasure.

Nevertheless, the Bush administration could have prevented much human suffering with better preparation and a more authoritative response. Katrina wasn’t a complete surprise. “We’d known for a while that the hurricane would be a bad one,” McClellan wrote in What Happened. On August 23, 2005—nearly a week before Hurricane Katrina made landfall in Louisiana—the National Weather Service (NWS) reported that a storm, named Tropical Depression Twelve, had formed over the Bahamas. By August 25, the NWS had upgraded Tropical Depression Twelve to a hurricane and renamed the storm “Katrina.” The NWS predicted that the storm would reenter the Gulf of Mexico, gain momentum in the Gulf’s warm waters, and make landfall again between the western tip of the Florida panhandle and New Orleans, Louisiana. As Katrina brewed in the Gulf, the National Hurricane Center made another series of predictions: Katrina would make its second landfall as a severe Category 4 or Category 5 storm; the hurricane would make landfall near New Orleans, which lies below sea level; and Katrina would cause flooding 15–20 feet above normal tide levels—high enough to overtop, and potentially break, New Orleans’s old levees. Federal, state, and local officials, as well as private-sector partners, were warned about what was coming 56 hours before Katrina hit the Gulf Coast.

Meanwhile, President Bush was at his 1,600 acre ranch in Crawford, Texas. The president had been away from Washington, DC for more than three weeks. The media proclaimed that Bush was “on vacation,” though McClellan contends that was not the case; the president continued to receive intelligence briefings and host visitors. Nevertheless, Bush was working with a reduced staff and reduced resources on site in Crawford, receiving his daily intelligence briefings in a secure trailer parked across the street, for example. Because he was in Crawford, Bush remained out of the loop as Katrina developed and the federal government prepared its response. The information Bush did receive came from Deputy Chief of Staff Joe Hagan’s occasional updates, but, according to reports at the time, members of Bush’s staff sought to bother the president as little as possible during his time in Crawford.

A storm was brewing. It’s unclear just how aware the president was, but Katrina’s development certainly wasn’t missed by the president’s staff and the executive branch. The same day the NWS reported that Tropical Depression Twelve had formed, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) activated its Hurricane Liaison Team. By August 25, FEMA had begun pre-positioning resources and aid from Texas to Florida. At logistics centers across the South, FEMA pre-positioned more than 500 trucks of water (977,000 gallons), over 400 truckloads of ice (4.6 million pounds), almost 200 trucks of food (1.86 million meals), and 33 medical teams in the largest preparation of federal assets before a natural disaster in the nation’s history. The Coast Guard was also on alert.

Bush, it appears, was not. Despite federal preparations for the storm, he remained in Crawford. It wasn’t until two days before Katrina hit land that he took action. After Louisiana’s Governor Kathleen Blanco requested that the president declare a state of emergency to trigger federal assistance, Bush declared a state of emergency for the state of Louisiana on August 27. The same day, FEMA went on Level 1 alert, its highest alert level. Bush issued emergency declarations for Mississippi and Alabama at the request of their respective governors on the following day. Though Bush was slow to act, this particular action was bold: A president had only issued an emergency declaration before the storm made landfall once before, preempting Hurricane Floyd in 1999. Nevertheless, the media continued to have a field day with Bush’s “vacation.”

Despite the emergency declarations, the president’s actions were insufficient. Bush’s unsatisfactory actions in anticipation of and throughout Hurricane Katrina stemmed from an improper understanding of federalism, the president’s constitutional powers, and powers afforded to the president by Congress under federal law.

Federalism, which grants the federal government limited powers and leaves other more general powers not assumed by the federal governments to the states, lies at the heart of the American system’s response to natural disasters. But there are inherent tensions when attempting to properly order and respect the sovereignty of both the national and state governments when devising plans to respond to natural disasters. When discussing Katrina in his book Decision Points, Bush expresses his concern for federalism in principle and statute: “By law, state and local authorities lead the response to natural disasters, with the federal government playing a supporting role.”

One can understand the sentiment, but Bush handicapped federal support by failing to exercise a number of authorities at his disposal.

Since 1988, the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (Stafford Act) has sought to balance federalism’s inherent tensions when America is confronted with a natural disaster. The Stafford Act establishes that state and local governments ought to lead in natural disaster response, but the act also provides a process for requesting federal assistance. To obtain federal assistance, state governors can request the president declare either an “emergency” or a “major disaster,” two distinct declarations that give the federal government similar powers.

An emergency declaration, which Blanco requested and Bush granted on August 27, provides the federal government with specific authorities to support state and local governments. But an emergency declaration also provides the federal government with general authority to increase federal support beyond the governor’s request when the “response to an emergency is inadequate” in order to “save lives, protect private property and public health and safety, and lessen or avert the threat of a catastrophe.”

A major disaster declaration, which Blanco requested on August 28 and Bush declared the following day, allows for a broad range of federal intervention composed of “essential” assistance, which supports the state and local response with federal resources, and “general” assistance, which hands the reins to the federal government. Through general assistance powers, the federal government is able to not only support state and local response efforts from State and local governments but also to take command over “coodinat[ing] all disaster relief assistance… provided by Federal agencies, private organizations, and State and local governments.”

Aside from powers granted to the president in the case of emergency or major disaster declarations, the president can declare an emergency unilaterally under the Stafford Act so long as the president, in his sole discretion, “determines that an emergency exists for which the primary responsibility for response rests with the United States.” Accordingly, the emergency must “involve a subject area for which, under the Constitution or laws of the United States, the United States exercises exclusive or preeminent responsibility and authority.” Given the severity of the storm, the likelihood that levees—built by the Army Corps of Engineers—would be overtopped and breached, and the dense concentration of federal (specifically military) assets in the predicted disaster zone, Bush could have decided to act unilaterally and taken command of the government’s response.

Furthermore, FEMA’s internal processes, empowered by Congress and created under Bush’s direction, provided Bush the ability to act more authoritatively. Bush had previously instructed FEMA, now under the newly created Department of Homeland Security (DHS), to develop the National Response Plan (NRP) for natural disasters. DHS Secretary Michael Chertoff was among those slow to act, eventually activating the NRP on August 30—a day after landfall. Activating the NRP allows the president and the DHS Secretary to classify an INS as a “catastrophic incident,” defined as:

Any natural or man-made incident, including terrorism, that results in extraordinary levels of mass casualties, damage, or disruption severely affecting the population, infrastructure, environment, economy, national morale, and/or government functions.

A “catastrophic incident” allows the federal government’s response to shift its posture from one of pulling resources to state and local governments to one of pushing resources directly to the affected area. In the end, Bush and Chertoff never declared Katrina a “catastrophic incident,” despite abundant warnings and evidence that state and local resources would be incapable of responding to a disaster of this magnitude.

The president had a number of other avenues to increase the federal response as well. In one of the extreme response scenarios available to him, the president could have declared a national emergency, which has been used from time to time in matters of public health and safety. But Bush waffled, a reaction which only became more costly as the crisis deepened. Between the multitude of federal agencies, state agencies, and local departments, there was no clear chain of command.

The executives involved in the response couldn’t even get on the same page. “Who’s in charge of security in New Orleans?” Bush recalls asking New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin, Blanco, and an Air Force One conference room full of legislators and staff in Decision Points. Nagin and Blanco pointed fingers at one another. The day was September 2, 2005—Katrina made landfall three days prior.

Bush admitted the government’s “response was not only flawed but, as I said at the time, unacceptable.” Mandatory evacuations, which Bush had to harangue Nagin into declaring, came only a day before landfall. Across the board, communications were sluggish at best and nonexistent at worst: Bush’s team didn’t even know the levees had broken on August 29 until the morning after. Power outages were widespread. Confusion reigned supreme while Chertoff attended an avian flu conference in Atlanta on August 30. FEMA had pre-positioned hundreds of trucks loaded with supplies, but the agency only started to deliver the relief on September 2, and continued asking for emailed requests for aid amid power outages and minimal wireless connection. Much of the FEMA aid was ultimately wasted; FEMA turned away deliveries and donations of emergency supplies and denied doctors who volunteered to offer assistance. A New York Times report read there was “incomprehensible red tape” amid simultaneous “uncertainty over who was in charge.”

Control and command issues beleaguered Nagin and Blanco, Chertoff and FEMA Director Michael Brown; but above all, they were a problem for Bush, who didn’t return from Crawford to Washington until August 31. During the last few days of his Crawford stay, Bush was privately becoming more engaged. For example, he joined a staff-level FEMA meeting by video on August 28. The same day, he pressured Nagin to declare a mandatory evacuation of New Orleans. Nevertheless, perception prevailed: The president was in Crawford.

In the early morning hours of August 30, the president’s staff determined it was time to return to Washington; reports coming out of New Orleans were worse than feared. Bush independently came to the same determination. He left Crawford but traveled first to San Diego for a pre-scheduled address to a V-J Day celebration, where he began the remarks by expressing his concern and prayers for those impacted by the storm. It was a compassionate speech, but what transpired after the address vastly overshadowed the president’s sentiments. Backstage was supposedly a place where the president could be more relaxed—no journalists, no cameras. Unbeknownst to McClellan, however, ABC’s Martha Raddatz, traveling in Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld’s entourage, had been brought backstage. “What is she doing back here?” McClellan asked. It was too late. Raddatz had snapped a picture of Bush strumming a guitar with the presidential seal gifted to Bush backstage by country-music singer Mark Wills. Shortly thereafter, the media began blasting out Raddatz’s snapshot aside devastating images from Katrina.

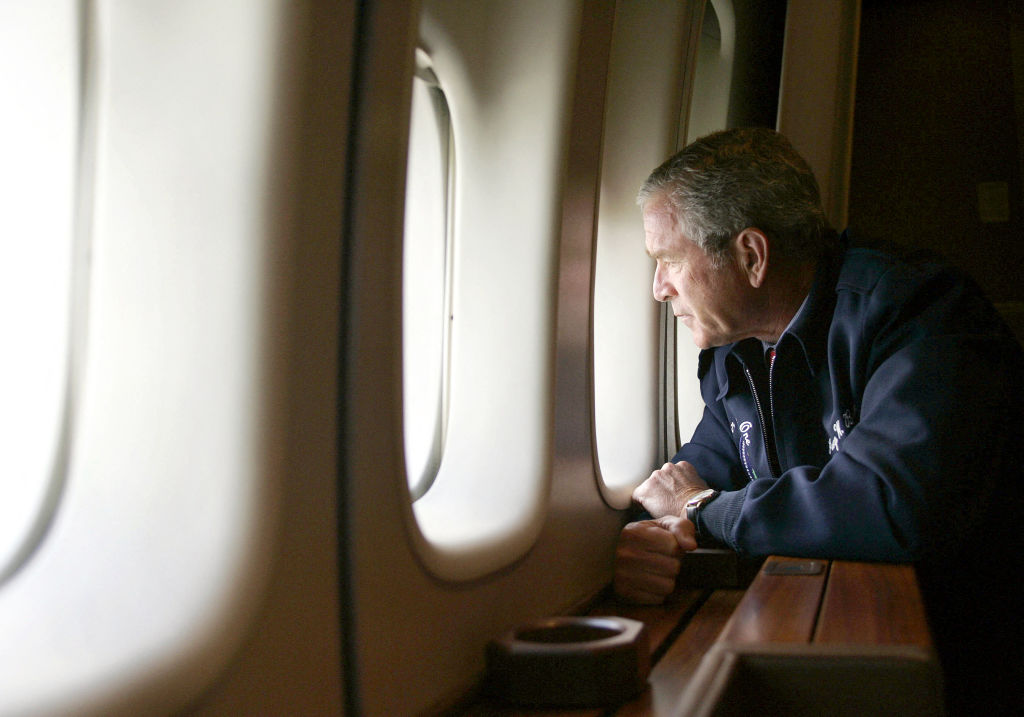

White House communications went from bad to worse. When the president’s staff initially discussed traveling back to D.C., Karl Rove had an idea: Bush would fly over the disaster area in Air Force One. The press secretary objected. “He’ll be 10,000 feet up in the air, looking down at people being rescued off rooftops. He’ll look out of touch and detached,” McClellan said, adding that Bush should either visit the impacted area on the ground or go straight back to Washington. McClellan ultimately won the argument, and the president and his staff decided not to visit the disaster area because it would take personnel and resources away from recovery efforts to accommodate the president. But Rove silently campaigned to the president that a flyover was necessary, and Bush eventually agreed with Rove. McClellan and others still thought it was a bad idea. As Air Force One decreased altitude, Bush stared in dismay out the window, astonished by the damage left in Katrina’s wake. Bush’s staff discretely brought in photographers to snap photos of the president. Bush wrote in Decision Points:

When the pictures were released, I realized I had made a serious mistake. The photo of me hovering over the damage suggested I was detached from the suffering on the ground. That wasn’t how I felt. But once the public impression was formed, I couldn’t change it.

“The photo-op of the man in charge staring out the window of his plane was disastrous,” Brinkley wrote. It “was the sight of a man slumming, a man in a bubble, a man deluged.” Privately, Bush allies would later admit the president could have visited the disaster area, as did Bush in Decision Points.

Matters didn’t improve when Bush eventually did visit. His September 2 trip included a walking tour of impacted areas followed by a press conference. In his remarks, Bush fixated on the destroyed vacation home of Mississippi Senator Trent Lott. “Out of the rubble of Trent Lott’s house—he’s lost his entire house—there’s going to be a fantastic house,” Bush said, adding he looked forward to sitting on Lott’s new porch. Later in his remarks, Bush, addressing Director Brown, said, “Brownie, you’re doing a heck of a job!” The line, like the images taken on Air Force One, portrayed to the public that the president had no idea what was going on. “Even Brown looked embarrassed,” McClellan writes. In a meeting after the press conference, Bush told his staff he was trying to boost morale and complimented Brown because the FEMA director was standing right behind him. McClellan and staff came to admit they had put the president in an impossible situation: praise an administrator doing an objectively poor job or ignore the man supposedly heading up the response. Bush chose the former.

But Bush had even bigger problems. New Orleans was quickly spiraling out of control. Looters were ravaging storefronts and private property; criminals acted with impunity; rescue shelters were out of key resources and experiencing ruthless criminality. Bush wanted to call in active duty troops to restore order, but Blanco denied the request. Bush, however, could declare federal troops law enforcement officers if he declared New Orleans in a state of insurrection. Presidents have invoked the Insurrection Act on more than two dozen occasions in American history to end violent strikes, labor disputes, riots, and to protect civil rights. President George Washington invoked the act during the Whiskey Rebellion; Jefferson, to stop violations of U.S. embargos; Eisenhower, to desegregate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. The chaos and carnage of Katrina matched or exceeded most previous invocations. Brown and other members of the administration pushed for declaring a state of insurrection, but Bush refused. His reason? “The world would see a male Republican president usurping the authority of a female Democratic governor by declaring an Insurrection in a largely African-American City.” Ultimately, Bush decided to send in federal troops without law enforcement capabilities. Under the command of Lt. General Russel Honoré, the troops were considered massively helpful, but it wasn’t enough for Bush to escape the accusations of racism he feared. Jesse Jackson proclaimed that the New Orleans Convention Center was the “hull of a slave ship.” The rapper formerly known as Kanye West was more direct: “George Bush doesn’t care about black people.”

By the time Bush delivered a primetime address from New Orleans on September 15, the damage to the Gulf Coast and Bush’s presidency was done. In September 2005, Bush’s approval ratings sank to the lowest it had been in his presidency up until that point, per a Washington Post-ABC News poll. In 2004, 60 percent of Washington Post-ABC News respondents claimed Bush could be “trusted in a crisis.” After Katrina, only 49 percent could say the same. Bush never recovered: “The legacy of fall 2005 lingered for the rest of my time in office.”

A presidency can survive an incompetent response to a crisis or failed messaging strategy, but not both at the same time. Like Bush, President Joe Biden learned this lesson the hard way in September of 2024, when his administration responded inadequately to Hurricane Helene, which hit North Carolina and other parts of southern and central Appalachia. The Biden administration pre-positioned large amounts of assets but had poor plans for distributing them across the tough terrain—much less the scandal that FEMA bureaucrats were directing aid away from folks with Trump regalia in their yards. When the Biden administration could not, or would not, provide aid, the people took things into their own hands: Search parties used four-wheelers and privately owned helicopters to find survivors, and mule trains shuttled collected donations deep into the hollers. Rather than applaud this American ingenuity and compassion, the Biden administration asked them to stop and actively obstructed their efforts. When a natural disaster hits, there’s an understanding that even the most powerful man in the world cannot fully conquer nature. What the public will not tolerate are actions that knowingly make the crisis worse.

Four months later, President Donald Trump inherited the disaster that Helene and Biden left in their wake. While the Trump administration’s efforts may still leave something to be desired by those affected, the message was strong: Biden, the Democrats, and their so-called experts failed you, and we will make sure they are held accountable. Since, the president has issued an executive order requiring a systematic review of FEMA and its processes.

Now 20 years removed from Hurricane Katrina, perhaps Trump is the one leader who has internalized the lessons from the disaster. He did not learn these lessons from reading a Vanity Fair article a decade ago. He learned them through trial, error, and perhaps some regrets—such as those about failing to “send in the troops” to stop Black Lives Matter riots in 2020. Gone are the days of Republican presidents being more concerned about the optics of a “male Republican president usurping the authority of a female Democratic governor by declaring an Insurrection in a largely African-American City.”

Trump is sending in the troops where he is able. First it was Los Angeles in June to protect federal property and federal agents from anti-law enforcement rioters. Then it was Washington, DC in August to combat the violent crime that has plagued the city for years without a proper response from local government. Now, Trump has started the process of sending troops to Portland, Memphis, and Chicago. And he’s floated the idea of sending troops to New Orleans. As the interventions in Los Angeles and Washington, DC suggest, the justification for these interventions vary—immigration enforcement, violent crime, protection of federal property. But the one through line is Trump’s penchant for making off-the-cuff remarks about invoking the Insurrection Act if push comes to shove. Certainly, it’s been invoked for much less in the past.