Loading the Elevenlabs Text to Speech AudioNative Player...

The final shot of The Red Balloon is one of the most exhilarating in any movie. In the moments leading up to it, a young boy sits on a hill in Paris, holding in his hands a deflated party balloon. He had loved that balloon, and, strange to say, it had loved him in return. But the other boys in his neighborhood, cruel and envious, took it, dragged it to a high place, and stoned it. It popped and fell to the ground. Now it seems all joy has gone from the boy’s life. But this is not the end. Suddenly, mirabile dictu, every balloon in the city comes rushing to the hilltop. The boy gathers them up into a great bundle, and together they lift off and drift out over the city. In the last shot, the Eiffel Tower is visible in the hazy distance. Then, the wind carries the boy and the balloons upward, leaving the entire world behind.

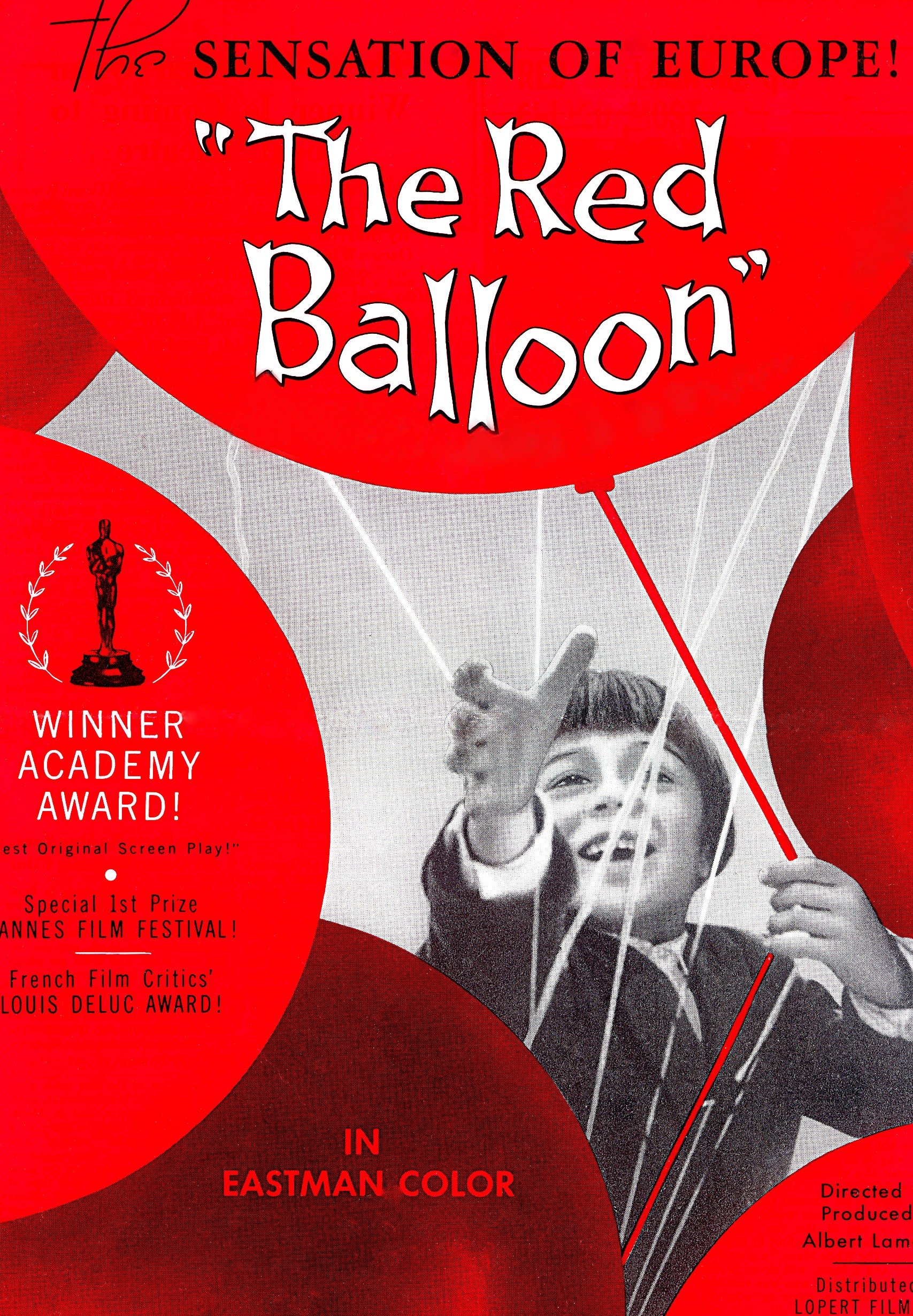

Ever since its release in 1956, the film has been beloved by children and adults alike all over the world. But for its director, Albert Lamorisse, that final shot presented a formal problem. Lamorisse’s first love was flight, and, had he his way, the camera would have lifted off with the balloons and followed them out over the city, across France, and down to Africa. But at the time this was impossible. Lamorisse could easily hop into a helicopter and shoot from the cockpit, but he knew very well that the footage he captured would be too shaky for use in a film which otherwise floats along like a dream.

Soon he became obsessed with solving his problem. In 1960, several years after The Red Balloon collected Best Screenplay at the Academy Awards, thereby securing Lamorisse license to do whatever he pleased, the director hit on a solution. With the aid of a marine gyroscope specialist, he developed a technology that he dubbed Hélivision. The tool is essentially airborne steadicam: a shock-absorbent frame mounted on a helicopter that reduces vibration when filming. Hélivision is so widespread now as to seem commonplace—the final alpine shots of The Sound of Music, for example, owe their grandeur to it—but at the time the invention was revelatory. It made it seem as if “the camera were mounted on a perfectly solid track in the sky,” one contemporary critic noted.

Lamorisse made liberal use of Hélivision in every subsequent film. It gave him the ability to do the things he had been unable to achieve with the end of The Red Balloon. In his follow-up feature, Stowaway in the Sky, the camera does lift off with the balloon, follows it over Paris, round and round the Eiffel Tower’s spire, and then out over Normandy and Brittany before finally setting down on the edge of the continent. By the late 1960s, the director was working almost exclusively in Hélivision, making documentaries in which he filmed past glories from novel angles. In the last of these, he swooped and dipped over the palaces and gardens of Versailles—and tumbled inadvertently toward his own downfall.

The trouble began in Persia. The shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, like many other Middle Eastern autocrats seeking global acceptance, believed that French arts and culture were his ticket to legitimacy. He of course kept an eye on the nation’s cinema, and when he saw Lamorisse’s Versailles documentary, he was electrified, even jealous. What the director had accomplished from his perch in the sky for Louis XIV’s great monument to himself, lovingly recording every detail of the fountains, the courtyards, the majestic staircases, the shah wanted done for his own works.

Of course, he also had practical reasons. In 1963, the Shah’s government had orchestrated the White Revolution, an aggressive plan for modernizing Iran’s economy and society. The first part of the program was modestly successful, the second part a disastrous failure. By liberalizing the state’s attitude toward the infidel, the shah had aroused the wrath of the Muslim clergy and provoked a dangerous (and ultimately fatal) enemy in the Ayatollah Khomeini. In the process, he had also angered other disparate groups within the country, many of whom rightly felt that his reforms were simply the consolidation of power under another name. By the end of the decade, the shah had become a brutal dictator, and his hold on the country was tenuous. His advisors felt that he needed something grand and artistic to reaffirm his claim to the Peacock Throne. Why not a film from a celebrated French director, showing off Iran in its full modern glory? Even better, why not peg the film’s production to the shah’s long-awaited coronation in 1967, as a sort of gift from the ruler to his people?

And so the shah invited Lamorisse and his family to Tehran. The director hesitated. He had a weird feeling about the whole affair and an even weirder dream about drowning in the Caspian Sea. But at last he found it impossible to resist the blandishments of the Persian court. He was promised free rein over Iranian airspace and ample state funding directed to whichever part of the country’s vast and varied landscapes he wished to film. He was even permitted, at state expense, to ship in his own helicopter, an Aérospatiale Alouette II, the one with which he had originally developed Hélivision. That settled it. Lamorisse came to Tehran and began work.

Almost immediately, however, he faced a narrative problem. Iran is a massive country populated by all manner of people. Its history stretches as far back as human memory, and it has been successively ruled by Assyrians, Medes, Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, Parthians, Arabs, and many others besides. Its religions are as numerous as its peoples, and not one of them—not even Islam—can truly claim lasting dominance. In the Western mind, Persia has alternately occupied a place of fear and fascination, from Herodotus to Gibbon to the present. There is no way for an outsider to depict its history and culture without running into some sort of trouble. Lamorisse understood these challenges, and, rather than attempt to address them, he looked for answers in Persian poetry, and came up with an elegant solution. He resolved to tell Iran’s story from the perspective of the wind.

Lamorisse’s intuition, airy as it sounds, had a touch of genius to it. The wind, like death, is an impartial force. It blows where it wills and over everything. In his brief study of Persia, Lamorisse found this was a far more interesting way to approach Iran than anything that the shah had proposed. The director did not care that the government was building new electrical plants, opening the universities to women, and erecting neon-lit highrises along the newly laid boulevards of Tehran. What fascinated him was the fact that all around these innovations lay the ruins of many great empires, with nothing but the wind whistling over their monuments to impermanence. And so he climbed into his Alouette, armed with Hélivision, eager to record the decay.

Throughout 1968, he shot hours of footage across the entire country. He began filming in the desert, then moved on to the historic cities, then down to the oil docks on the Persian Gulf, and, finally, up north by the Caspian, he captured an incredible sequence on a carpet-strewn mountain. His methods on location were simple. Lamorisse stationed himself with a camera and pilot in his own helicopter while an Iranian military chopper followed close behind, kicking up the dirt to give the effect of wind. Everything was filmed en plein air; nothing was faked on a soundstage. Lamorisse glides down the mountains, between minarets, and over blazing oil fields with utmost confidence.

The film’s story is also simple, almost simplistic. It is narrated by Badeh Sabah, the Lover’s Wind, a kindly northwestern breeze. (His name gives the film its title, The Lover’s Wind.) At the beginning, he is put to flight by his cruel brother, Badeh Div, the Devil Wind. Over the course of the film, Badeh Sabah visits many different regions of Iran, gradually gains confidence, and eventually defeats his overbearing brother in a comic showdown. The narration is provided in Persian by the director Manouchehr Anvar, who supervised its translation from Lamorisse’s French screenplay. In the film’s English dub, whose translation Anvar also provided, the narrator sounds like a charming, downmarket Peter O’Toole.

About a third of the film focuses on the wreck of the Persian empire. In an early scene the winds rush over the remains of Susa, which thousands of years ago served as the winter capital of the Achaemenid Empire. Now there is nothing left but crumbling citadels, ruined houses, dunes pouring into the streets. “Here, generation after generation, people toiled and rejoiced,” Badeh Div declares. “But we have buried everything.” Only the nomads wander through the ruins.

“Fifteen cities have grown and died here,” the cruel wind continues. “Each had their great scholars, their great politicians, their great warriors, their great artists. Each claimed not only to be the most beautiful city on earth, but also the mightiest and the wisest. Fifteen times we have overlaid them with dust and sand.”

In the next scene, the winds visit Persepolis, the old Achaemenid ceremonial capital, burned to the ground by Alexander the Great. Badeh Div boasts that while the Greeks may have started the fire, he and his companions were responsible for feeding the flames. “Such was their roaring that it drowned the shrieks of the dark crowd jammed in the streets and the alleys,” he tells his brother. “We blew very, very hard indeed.” As the narration rolls over the scene, the sun sets, and the broken pillars appear as jagged silhouettes standing out against the empty desert.

The most striking part of the film—like something out of a Persian Koyaanisqatsi—occurs only minutes later as Badeh Sabeh surveys the docked oil tankers bound for the Strait of Hormuz. The camera turns to the shore, revealing an array of shining smokestacks. “I caught sight of silhouettes suggesting a sort of new Peresoplis,” the wind observes. Curious to see where the oil comes from, he decides to follow the pipelines to their source. He begins at the refineries on the shore and flies out over miles and miles of pipes, captured in a dizzying unbroken shot: across scrubland, up mountains, zig-zagging through deserts, down ravines, over rivers, shackling the land until they terminate in the fiery oil fields themselves. This is the second Persepolis. And, just as the first one was the spiritual center of the Persian empire, so too is this new one the animating force of the modern Iran.

“This is how men have learned to tame the fire they had worshiped, but when you make use of gods, there are always drawbacks,” Badeh Sabah muses, adding that the world’s dependence on this industry “seemed like a frightening riddle whose answer meant life or death for the earth.”

Obviously, this is not the film the shah asked for. Although Lamorisse does include some brief shots of modern city life (including one pass at the old Royal Tehran Hilton), the majority of the work is a ruminative reflection on the past. About the present, it is ambivalent. And about the future, it offers only a warning: Great nations fall. Nothing but wind remains.

As far as Lamorisse was concerned, his work was finished. But the shah would not let him get away so easily. He had opened his checkbook to the director, and now he felt cheated. In 1970, Iran’s Ministry of Art and Culture requested that Lamorisse return and add additional scenes under its close supervision. This time, the regime would not pay for him to bring his own helicopter or pay the salaries of his French film crew. He was to work with Iranian instruments on Iranian terms.

The director did not want to go. He had plans for a new project in the United States. But at last he consented. And almost as soon as he arrived in Tehran, he regretted his decision. The ministry picked out a number of unobjectionable locations for him—a university, a research lab, a car manufacturing plant—that he dutifully filmed. But there was one request to which he could not readily assent: a jaunt out to the Karaj dam, a massive structure northwest of Tehran, built by an American firm from Idaho and one of the jewels of the Shah’s modernization efforts.

The problem, Lamorisse objected, was the high tension wires above the dam. It was not safe to fly a helicopter at a low altitude around them. On this point he was insistent. But the ministry was more insistent. And since its word was law, off he was sent in a military chopper flown by the shah’s personal pilot.

Anyone could predict what happened next. As the helicopter banked in low over the dam, it became entangled in the wires. The pilot, the crew, and Lamorisse fell to their deaths—all the way down to the brilliant blue water below.

The craft remained trapped above, and it is hung up to this day. It is the ultimate tribute to Lamorisse’s final work. Like the ruins of Susa and Persepolis, his wreck has outlasted the shah’s rule, and, if current events are any guide, it may well outlast that of his successors. In the end, the wind will also blow it away, as it does everything else.