Most of the classic British gangster film The Long Good Friday is set in London's docklands at the end of the '70s. Which means we get to see long shots of abandoned warehouses, empty quays and endless rows of now-useless cranes against the low clouds. It wraps the film in an elegiac mood, expressed by its protagonist Harold Shand (Bob Hoskins), a London gang boss looking to go legitimate by leading a group planning to redevelop the docklands in anticipation of London hosting the Olympics in 1988.

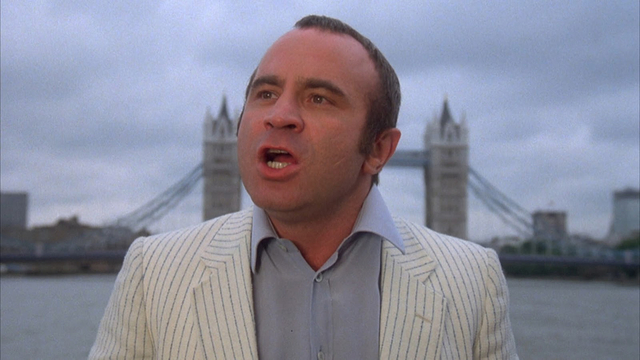

Harold is the undisputed king of the London underworld after ten years of peace and cooperation between all the firms in the city, and his territory is based on the north side of the Thames – Wapping, Limehouse, Shadwell, Hackney, Canary Wharf and the City of London. He has put together a coalition of partners on both sides of the law, including Charlie (Eddie Constantine), an American mafiosi, but while taking them all on a tour of the Thames downriver from Tower Bridge, he can't help but wax nostalgic to Charlie about when the docklands were bustling, with ships moored in line waiting to be unloaded.

The docks and the East End had been pummeled during the Blitz, but it was container shipping that did them in, and by the end of the '70s there were endless plans on how to revive this vast industrial wasteland, including an Olympic bid for the Isle of Dogs. (Seoul would ultimately win the bid for the 1988 games; London would host them in 2012, building an Olympic park in Stratford, in the most northern part of Harold's territory, the docklands having long since been redeveloped.)

Harold is told by his American colleague not to be nostalgic, so with Tower Bridge behind him he gives a speech to his investors regaling them with his vision for the future of his city. "I'm a businessman with a sense of history," he says, "and I'm also a Londoner." He predicts that London will lead the Common Market and become Europe's capital. "Having cleared away the outdated," he tells them, they have acres of land in their heart ready to be redeveloped – "an opportunity for profitable progress" if the right people undertake the job. He introduces his "American friends" and proposes a toast to "hands across the ocean."

It's a bold vision and screenwriter Barrie Keeffe has been credited with remarkable foresight in predicting what would happen in the next two decades. Critics have even described Harold and his vision as "Thatcherite" but considering that Margaret Thatcher was elected barely halfway through 1979 this is more like hindsight; it's like when punk is described as a reaction to Thatcher when the punk moment – really a reaction to social and economic decline under Labour – was over when Thatcher arrived at Downing Street.

(In context the real musical reaction to Thatcher was New Romanticism; something to think about when you put on your Visage, Duran Duran and Spandau Ballet records, and this is far from an original thesis.)

Harold gives his speech to his backers at the beginning of Easter weekend, but even before he does we already know that his plans are going to be seriously disrupted. Because as the credits rolled we saw a sequence of apparently disconnected events: a group of men waiting in a cottage in the countryside, a man walking off a boat with a suitcase full of cash before pocketing some of that money in the backseat of a car, that suitcase being handed off before being delivered to the men in the cottage, the man who brought the suitcase picking up a young man in a pub, the men in the cottage realizing that cash is missing before being surprised by gunmen, the man with the suitcase being left behind at the pub after his driver and the young man are abducted by more gunmen, their bodies being dumped by the side of a country road and a finally a casket arriving at Paddington Station where a widow in black is waiting.

All this makes its way back to Harold on the patio of a restaurant where his right-hand man and protégé Jeff (Derek Thompson) is given a set of secret planning drawings by city councillor Harris (Bryan Marshall), a key member of Harold's group of backers. After he leaves the widow has the funeral cortege stop so she can spit in Jeff's face – a bit of drama noticed by Harold's bodyguard and driver Razors (P.H. Moriarty) from across the street.

It gets even closer just as Harold is making his speech. His mother attends Good Friday mass and the Veneration of the Cross while his driver waits with his Rolls Royce outside; impatient to get away he starts up the car early and sets off a car bomb. At the same time Colin, the man with the suitcase (Paul Freeman) is cruising a handsome young man at a swimming pool; beckoned into a shower stall he's knifed to death. (The young assassin, a crucial but wordless role in the picture, was played by Pierce Brosnan in his first movie role.)

Barrie Keeffe had talked with producer Barry Hanson about writing an American style gangster film set in London; Hanson commissioned him and Keeffe wrote a draft titled "The Paddy Factor" in a weekend. When Hanson's employer, a subsidiary of Thames Television, opted not to make the picture he bought the rights for his own company but hit a snag when Black Lion, part of Lord Lew Grade's ITC Entertainment, produced it to air on ATV, his television network.

The closest comparison to Harold Shand in real life would have been someone like Freddie Foreman, an associate of the Kray brothers who returned to crime on his own after their imprisonment at the end of the '60s. He masterminded a £6 million robbery in 1983 and went on the lam for six years until he was dramatically arrested in Spain six years later. Villains like Foreman, alongside movies like Get Carter and The Long Good Friday, would be the foundation of the revival of the British gangster film starting in the '90s with directors like Guy Ritchie and films like Layer Cake, In Bruges and Sexy Beast.

Director John Mackenzie began his career as an assistant director to Ken Loach on his early television films Up the Junction and Cathy Come Home, which got him jobs directing television plays until A Sense of Freedom, his movie about Glasgow gangster Jimmy Boyle caught the attention of Hanson. With a budget of less than £1 million they shot on location in London, from St. Katharine Docks next to Tower Bridge to the Isle of Dogs to Wapping, Lewisham, Wandsworth, Dagenham, Harringay and the Savoy Hotel.

Bob Hoskins had started his career onscreen playing a recruiting sergeant in Up the Front, a Carry On picture, alternating parts on TV in Play for Today, Thick as Thieves and the original BBC version of Dennis Potter's Pennies From Heaven with movies like Royal Flash, Inserts and Zulu Dawn, during which he contracted a tapeworm while eating raw meat in a tribal ceremony. Keeffe wrote the role of Harold for him, and the role of his girlfriend was given to Helen Mirren, known more as a theatre actor though she'd appeared in pictures like Michael Powell's Age of Consent and Lindsay Anderson's O Lucky Man!, not to mention the notorious big budget porn epic Caligula.

As originally written by Keeffe, Mirren's Victoria was little more than a gangster's moll so the actress risked her job by imploring Keeffe and Mackenzie to make her more of a central figure in Harold's success. Harold is aspirational and Victoria is crucial to his rise from gangster to legitimate businessman. Her posh upbringing – she once moved in the same circles as Princess Anne – is key to him making the right transactions on his way up through a British class ladder that had been opened up (albeit briefly) in the aftermath of the '60s.

Mirren's instinct was sound; Harold could have been little more than a thug putting on airs but in key scenes where he not only respects her opinion but needs her to calm his rages we get a glimpse of something new: a criminal either blessed or cursed with self-awareness. Harold is surrounded by associates bonded to him by fear as much as anything else, likely to flatter him as easily as they'd take a chance to replace him. Victoria's is doubtless motivated by proximity to power and influence, but Hoskins and Mirren have great chemistry and make it plain that there's real love between Harold and Victoria.

Harold needs her help as the attacks on his empire continue, with a dud bomb in his casino and one that blows up a pub he owns seconds before he was supposed to arrive with Charlie for a celebratory dinner. He's blindsided by this relentless offensive but baffled about where it could come from. The audience has been given just enough of a clue that we're a step ahead of Harold for most of the movie.

The moral curiosity of gangster films is that audiences inevitably end up sympathizing with the criminal protagonist and his whole organization even when we know that organized crime is a dangerous parasite, and that we'd never want it to touch our lives. Gangsters were the earliest antiheroes as played by sympathetic tough guys like Cagney and Bogart, but the Godfather films created the playbook for this misguided identification, Martin Scorsese refined it with Goodfellas and David Chase played with in The Sopranos, occasionally testing the limits of our sympathy for charismatic criminals.

The Long Good Friday lets us see the range of Harold's ruthlessness in its most iconic scene, where he has the foot soldiers of his firm round up the heads of all the lesser London crime firms for interrogation. The men are taken to an abattoir – the same one where he's keeping the body of Colin, his oldest and closest friend, on ice. Hanging upside down on hooks next to ranks of carcasses, they're harangued by Harold and left to shiver until one of them gives him an answer.

Harold had already pressured Parky (Dave King), his bought and paid for cop, to give up his best informant. He sets the aptly-named Razors with a machete at Errol the Ponce (Paul Barber), standing naked in his own kitchen, to no satisfaction. But he finally gets an answer when Parky shows up at the abattoir and lets him know that the dud bomb from his casino is the work of the IRA, made with explosives stolen from the warehouse of the construction firm owned by Councillor Harris.

Ten years is a crucial interval in The Long Good Friday; Harold reminds Victoria early in the film that it's been ten years since his divorce, and she tells him later that his rise to the top of London's underworld has meant ten years of peace on the streets. In 1979 it had been ten years since the Battle of the Bogside in Londonderry ignited the Troubles – a decade of British army occupation, bombings, assassinations and the collapse of Ulster's government at Stormont.

It was a disaster for Northern Ireland and it would afflict the whole UK over the next twenty years. The Troubles seem like ancient history now, far enough in the past to become a hit comedy series on Netflix, but it was a serious, terrifying subject at the time. It turns out those men in the cottage at the beginning of the film were IRA, and while Harold was away in America, Councillor Harris had asked Jeff to do him a favour and send one of his men to Belfast with money for the Provos.

It took a lot of money to pay for the war in Ulster, and the IRA were happy to get support from anywhere, whether it was Muammar Gadaffi's Libya, the PLO, their own organized crime endeavors or the tip jars you used to find in Irish bars in New York and Boston. As with any mobster worth their reputation the IRA ran protection rackets, like the one that kept Councillor Harris' Irish workers from striking.

It was bad luck that Colin took a cut of Harris' money for himself, and even worse luck that the Provos were raided just after they took delivery of his suitcase. This made Harold and his organization look like he grassed them out and kicked off a war of retribution at the worst possible moment for a gangster hoping to go legit, all the more terrifying when it seemed to come out of nowhere, making anyone a potential target.

One of the best scenes in the film happens after the pub bombing, when Victoria was forced to level with Charlie and let him know what Harold was up against. After Jeff comes on to her in the elevator of her apartment building Harold arrives home with his first real clue about the enemy they're facing. He's furious that she told Charlie the truth but apologizes when he realizes that she's truly, utterly terrified.

The IRA's three decade terror campaign had that effect on British citizens who realized that they could become victims of random bombings, and especially on the British establishment who knew that they were the most effective targets of the terrorists, and seemed able to reach anyone, anywhere – like Lord Louis Mountbatten, killed in a bombing in the summer of 1979.

Harold and the men in his firm might be killers, but their motivation ends with money. This isn't the case with the IRA, who crucify a security guard to the floor of Harris' warehouse when they're told he could identify them. Jeff warns his boss about them when he admits that he made his firm a target of the Provos, just before Harold kills his protégé in a rage. Harris repeats this warning, telling Harold that the IRA aren't just another bunch of gangsters – they're fanatics who will keep coming. But Harold can't seem to comprehend this kind of danger, and has Harris killed along with the IRA's men in London, in a great scene at the demolition derby at Harringay Stadium.

Harold is confident that he's solved the problem when he arrives to find Charlie about to check out of the Savoy and fly back to America, spooked by the mayhem he's witnessed. "We do not deal with gangsters," Charlie's mob lawyer scolds Harold. "This country is a worse risk than Cuba was. It's a banana republic. You're a mess."

Harold is outraged. "Us British, we're used to a bit more vitality" he rants at his American colleagues. "What I'm looking for is someone who can contribute to what England has given to the world. Culture. Sophistication. Genius. A little bit more than a hot dog, know what I mean? We're in the common market now, and my new deal is with Europe. I'm going into partnership with a German organization. Yeah! The Krauts! They've got ambition. Know how. And they don't lose their bottle."

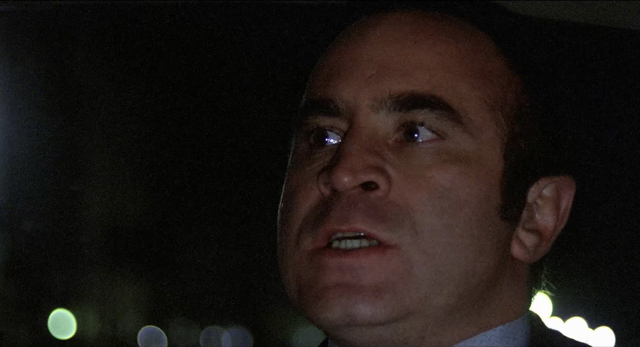

It would be a stirring, even heroic moment, but when he gets in his car outside the hotel he's pushed back in his seat when the driver speeds away, then sees Victoria in another car, screaming for help as she's driven off in another direction. Brosnan's Irish killer rises from the passenger seat pointing a gun at him and the camera stays on Harold for the last minute of the film, as emotions play silently across his face – fury, revenge, admiration and then finally acceptance of a fate he cannot control.

Lord Grade hated the film, complaining that it glorified the IRA. ITC planned to broadcast the film in the spring of 1981 after cutting it heavily; even worse they intended to have a non-Cockney actor dub Hoskins' dialogue – a move they had to abandon in the face of terrible publicity, with prominent actors, including Sirs Olivier, Gielgud and Richardson, making outraged statements about Hoskins having his voice taken away.

Fortunately Hoskins ran into Eric Idle of Monty Python at a party and asked if they'd be interested in buying a film with the money they'd made from Life of Brian. Idle passed the word on to George Harrison's Handmaid Films, who bought The Long Good Friday for £200,000 less than it cost to make, sending it out on to the festival circuit and releasing it into theatres in 1980.

It was a hit, and Hoskins was nominated for a BAFTA, kicking off a career on both sides of the Atlantic that lasted until his death in 2014. Helen Mirren said it's one of her top five films.

"Bob was just electrifying," she recalled. "It was the role of his life. That feeling of being a bomb that's about to go off."

"I knew that Bob was giving an amazing performance. But I wasn't so knowledgeable about film-making then, so I really wasn't aware what a muscular, visceral piece of work it was. I didn't know, but John (Mackenzie) was at the height of his career. He knew."

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.