There were over eleven million Americans in uniform in the summer of 1944, when Since You Went Away hit the theatres. But they weren't the audience for the picture; that would have been the millions of families either waiting for them to come home or mourning their death – the homes with the blue and gold star flags in their windows. Incidentally the MGM picture would make its way to training camps and bases and bivouacs behind the lines, where soldiers could have their fantasies about the home front buffed up by the kind of big budget propaganda Hollywood's biggest studio set itself to with the best of intentions.

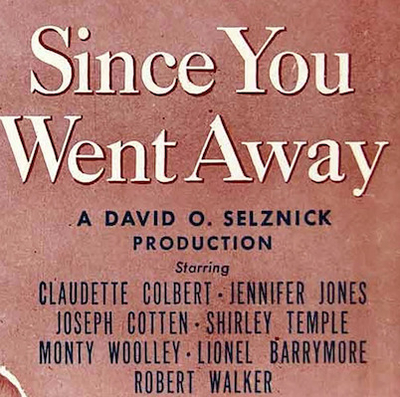

Since You Went Away was a David O. Selznick production and a prestige release – nearly three hours long with an overture and intermission. And like many Selznick productions around this time it starred Jennifer Jones; the infamous affair the producer had with the actress began in earnest when the picture went into production. That he also cast her husband as her love interest in the picture is a detail which has given this otherwise anodyne drama a notorious reputation in hindsight.

Selznick's career peaked with Gone with the Wind, and he'd spend the rest of his life trying to make that lightning strike twice (though never succeeding). He'd taken a bit of a sabbatical after the success of Rebecca in 1940, during which he closed the doors at Selznick International Pictures and put together feature film packages to sell built around the studio's contract artists, including Alfred Hitchcock, Ingrid Bergman and Vivien Leigh. (Hitchcock, for his part, was grateful to be temporarily free of Selznick's relentless interference during production.)

During this period he encountered Jones for the first time, when the New York theatre actress had what she assumed was a dismal and tearful audition for the lead role in a film version of the hit play Claudia. Selznick liked what he saw and put her under contract with his studio, and though he never made a movie of Claudia with Jones, she rocketed to stardom in the 20th Century Fox production of The Song of Bernadette in 1943, winning an Oscar for best actress.

She had married Robert Walker in 1939 when she was still Phyllis Isley and they were struggling young actors on the east coast and, despite having two children with Walker, began an affair with Selznick, who gave her a new stage name; she waited until her Oscar win to announce their separation, which devastated the emotionally fragile Walker. Her relationship with Selznick – they finally married in 1949 and she would stay with him until his death in 1965 – would define her career and cloud any objective assessment of her talent right up until today.

Since You Went Away is based on an epistolary novel by Margaret Buell Wilder, a collection of letters from a wife to her husband while he's away in military service. The movie, directed by John Cromwell from a script by Selznick, covers a year in the life of Anne Hilton (Claudette Colbert) – 1943 to be exact, the second full year of America's participation in World War 2, and now considered the most critical year of the war. 1942 had been the turning point with Stalingrad, Midway, Guadalcanal and the North African campaign, though nobody really knew it at the time, and the next year would be the one that consolidated 1942's hard-won successes and began the costly beating back of Axis armies to German and Japan.

But that was all happening far away from the United States, and the film begins (after Max Steiner's overture) with the credits rolling over a blazing hearth – the symbol of the home for centuries. Titles tell us that "This is the story of the Unconquerable Fortress: the American Home 1943." We meet Anne Hilton just after she's seen her husband off at the train station.

Tim Hilton remains offscreen for the whole picture, but we know that he's an advertising executive in an unnamed midwestern city. The Hiltons are situated firmly in the middle of the middle class, and though Tim could have remained out of uniform due to his age and family status, he chose to enlist out of principle – a sacrifice that both he and his family will have to bear.

The first sacrifice that Anne and her daughters Jane (Jones) and Bridget (Shirley Temple) have to bear is their longtime maid Fidelia (Hattie McDaniel). Without Tim's salary they can't afford her wages, and even though Anne gets her a position with a wealthy family, Fidelia asks if she can move back into her old room and even volunteers to cook and clean for Anne (whose domestic skills neither of them regard highly) in her off hours in exchange for board.

They also decide to take in a boarder to make some extra money and ease the housing shortage, and while the boy-crazy Jane hopes for a handsome young officer, they end up with Colonel Smollett, elderly and retired and employed in some unnamed capacity with the Army. The Colonel is played by Monty Woolley, doing an only slightly less caustic variation on Sheridan Whiteside in The Man Who Came to Dinner.

Into the vacuum created by Tim's absence comes Tony Willett (Joseph Cotten), an old friend of the family and an old beau of Anne's. He made his living as a pin-up artist before taking a Navy commission, and he presents Anne with a gift when he visits – a huge cheesecake recruiting poster with Anne's leggy likeness, implausibly rejected by the Navy. Jane has a crush on him but he only has eyes for Anne and takes the opportunity of his posting at the military base just outside town to obtain a berth in their home.

Cotten has obvious fun playing the charming yet caddish Tony, who flirts relentlessly with Anne in the vain hope of either cuckolding his old buddy or somehow reversing time to the point where he might have been the winning suitor and not just a casual Lothario operating with the unfair advantage of a Navy dress uniform. Their father might be their hero, but Cotten's Tony is the masculine ideal for Jane and Bridget.

The film's dramatic element arrives in the form of Corporal Bill Smollett (Walker), the Colonel's grandson, also stationed at the nearby base. The boy has been a disappointment to the old man and the family's long military history; he'd washed out at West Point and only found his way back into uniform as an enlisted man.

He shows up at the Hilton's door hoping for a reconciliation with his grandfather but returns when he falls for Jane. What follows is a test for the two young people: Jane needs to grow up and replace her infatuation with Tony with a more appropriate one, while Bill has to prove himself worthy of Jane's affection.

Bill needs to overcome a perception that he is "weak" to realize his potential as a man and as a soldier. Walker would play various GIs and airmen during the war, in pictures like Bataan, The Clock, Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo and in the Hargrove comedies. He was everyman in uniform, a representation of the average young man facing challenges civilian life would likely never put in front of him, and Since You Went Away is particularly explicit about how these young men were having their courage tested by the likelihood that they'd be in battle.

The home front picture was a popular counterpoint to the war movies made by Hollywood. Along with The Clock there was a similar romantic drama, I'll Be Seeing You, with Cotten and Ginger Rogers instead of Walker and Judy Garland. And there was Tender Comrade and The Major and the Minor (with Rogers) and countless other romantic comedies, screwballs, dramas and even proto-film noirs – a list that includes Hail the Conquering Hero, The Human Comedy, The More the Merrier, Sunday Dinner for a Soldier, You Came Along, The Miracle of Morgan's Creek, Air Raid Wardens, Christmas in Connecticut, The House on 92nd Street, The Doughgirls, Three Hearts for Julia, The Very Thought of You, Dark Waters and many more.

Details of home front life fill every scene in Since You Went Away, including rationing, shortages and the disappearance of decent food from restaurants. Like the Washington DC streets in The More the Merrier, public spaces are full to bursting, none more so than hotels, trains and railway stations. (Blink and you'll miss Dorothy Dandridge as a GI's wife in one train station scene.)

Selznick's script crams snippets of overheard dialogue into these crowded spaces – people complaining about the war, the black market, soldiers, moral decline, refugees and the poor quality of food. The closest thing to a villain in the picture is Emily Hawkins (Agnes Moorehead), a rich widow and a friend of Emily's who has made herself the social centre of the town by literally trucking local girls to the nearby base for dances. She's also a hoarder who has filled a cold storage room in her house with goods before rationing hit.

Just over halfway through the film Anne gets bad news in a telegram: Tim is missing in action. Jane graduates high school and defers college to work as a nurse's aide in a rehabilitation hospital for wounded soldiers. The experience sobers her up and makes her more receptive to Bill; their relationship becomes serious and they get engaged before he ships out, with Jones running after his departing train while they pledge their love to each other.

Nobody knew why Selznick was so intent on casting Walker in the film; he and Jones had separated during production, Walker moving out of the home they shared with their two sons and into a hotel where he got to work on the alcoholism that would nearly destroy his career. Filming was complicated, in classic Selznick fashion, with three cinematographers working on the picture and three uncredited directors, including Selznick, taking over from James Cromwell, including Edward F. Cline (The Bank Dick, My Little Chickadee, Bringing up Father) for the comedy sequences.

And Selznick insisted on being on set for scenes with Jones and Walker, making them do repeated takes during love scenes. Screenwriter Dewitt Bodeen (Cat People, I Remember Mama) was on the Selznick lot during filming and recalled that "it must have satisfied a masochistic urge on his part to see the two of them kiss and embrace. I was a little surprised that Bob didn't walk out. As for Selznick, he wanted Walker for the part and no one but Walker."

Selznick's script paints Bill as particularly callow and gormless, abjectly following Jane around, and it's not surprising that Walker's performance has a perceptible hint of hysteria that's missing from his similar role in The Clock a year later, by which point he would disappear on benders, from which he was rescued by Judy Garland, her publicist and make-up artist. And then Selznick's script has Bill killed in action in Salerno, during the Allied invasion of Sicily.

Shirley Temple had been effectively retired from movies for two years when she made Since You Went Away – since a notorious meeting at MGM with producer Arthur Freed, who exposed himself to the teenager. She would also recall being warned about Selznick, who took off his shoes when he came on to actresses. Sure enough she found him in his stocking feet during a meeting, which she spent evading the portly producer as they circled his desk.

Claudette Colbert had to be persuaded to take on the role of Anne, which she initially turned down because she didn't want to play a mother of two. (She was nearly forty when she made the film; Jones was twenty-five and Temple just sixteen.) It had been just two years since she'd played the runaway wife in Preston Sturges' screwball classic The Palm Beach Story, followed by a heroic army nurse during the fall of the Philippines in So Proudly We Hail! and another screwball heroine opposite Fred MacMurray in No Time for Love.

She would hold off on another mother role until Family Honeymoon in 1949, but her Anne in Since You Went Away is distinctly Miniverian – a chic and attractive mother who can turn heads in a bar and make Cotten's Tony carry a torch for her. But the film is nobody's best work, thanks mostly to Selznick's mawkish script and the need to keep the tone light despite the somber facts of home front life in 1943.

Selznick liked to spend money and despite the film's massive budget – over $3.2 million – it was a massive hit, making over twice that at the box office and picking up nine Oscar nominations (but only winning one for Max Steiner's score). By this point Jones' relationship with Selznick was an open secret; she would co-star with Cotten again – as her legitimate love interest – in Love Letters and Portrait of Jennie, and Selznick would strive mightily to both make her a sex symbol and re-create the phenomenon that was Gone with the Wind with the notorious western Duel in the Sun. Selznick would destroy Michael Powell's Gone to Earth by butchering the U.S. release of the picture, trying to make it a showcase for his wife. In the meantime Jones would credit herself with her performances in Ernst Lubitsch's Cluny Brown, in Vittorio de Sica's Terminal Station and in John Huston's Beat the Devil, but the perception of her as Selznick's project never really allowed for a clear view of her talent.

Walker and his career would suffer from both depression and alcoholism, and he had a brief marriage to John Ford's daughter Barbara. He'd manage a career-defining performance as the villain in Alfred Hitchcock's Strangers on a Train in 1951 but that same year he'd die when the alcohol in his system reacted with a shot of amobarbital administered by his psychiatrist during a manic episode. He was just thirty-two.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.