We've long passed the point where we expect truth from documentary filmmaking. The thin line between documentaries and propaganda (which is to say documentaries that advertise their bias) meant that this was always never a reasonable expectation. This doesn't mean it's impossible to enjoy documentary filmmaking, but it does mean that you need to be wary of that moment when a film's bias and your own worldview fit together with an audible click.

Barbara Kopple's Harlan County USA, which won the Oscar for best documentary in 1977, is one of those documentaries that neither flatters my prejudices nor tips its hand so eagerly and early that I know I'm having my time wasted. How you will respond to the picture probably depends on how well you remember the political and economic turmoil of the '70s, the place you grew up on the slippery scale of class, and how you feel about organized labour.

Kopple's film is a time capsule; the issues that inspired her story are still around, but so much has changed since then that where they resonate most deeply in the voting booth has undergone a polar shift. As far as I can tell the only thing that hasn't changed since Harlan County USA was released – probably because it hasn't changed in all of human history – is that mining in general and coal mining in particular is the worst job in the world.

Kopple's film begins by taking us down into an Appalachian coal mine with the men who work there, as they descend into the depths by throwing themselves onto a rubber conveyer belt or emerge from a pit entrance lying nearly flat on low-slung vehicles that barely clear the ceiling of the shaft. Headlamps pierce the inky darkness as the men carve into coal seams that fracture and collapse, tunneling foot by foot into catacombs that could quickly become graves.

The walls sweat but the humidity can't keep down the black dust that fills the air. The claustrophobia is palpable and unbearable. And it must be remembered throughout the hour and a half that follows that this is the job that the men at the centre of Kopple's film (supported, it must be noted, by their wives and mothers) are fighting to keep.

The subsequent action takes place around a strike by the miners at the Brookside Mine, between Harlan and Evarts in southern Kentucky, against the Eastover Coal Company and their corporate parent, Duke Power Company. This was not the story that Kopple and her crew had set out to document when they began filming in 1973, but it serendipitously provided the framework to hang a whole story about miners, unions, and a region that's been described as "America's third world".

The strike was an echo of a violent chapter in the history of organized labour in the U.S., when Harlan County earned its nickname "Bloody Harlan" during a series of skirmishes and pitched battles between miners and strike-breakers protected by mine guards and National Guard in the early '30s. It would be a terrifying example of civil unrest if it didn't happen in a decade full of similar outbreaks of violence between desperate workers and agents of either industry or government. Kopple and her crew would have known this when they arrived in the area just as efforts to organize the Brookside miners by the United Mine Workers of America turned into a strike.

Kopple starts painting in historical context by interviewing a veteran miner who began his career as a "breaker boy", separating slate from extracted coal for literal pennies. He recalls striking against the meagre pay and abusive conditions and being advised to give up the fight not just by local politicians and the local Catholic priest but by union officials who considered it a distraction to their ongoing relationship with the mine owners. It's a theme that will echo throughout the film.

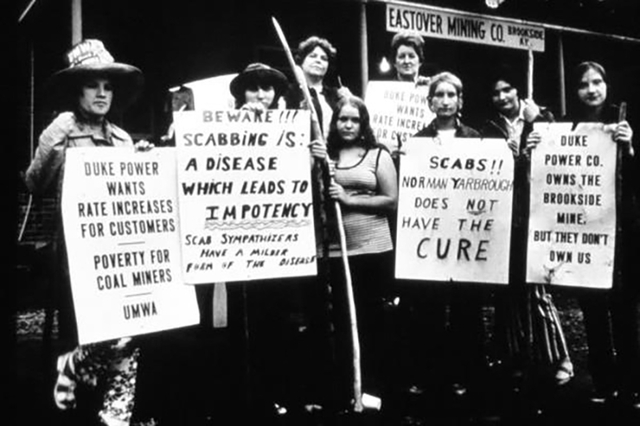

As the Brookside strike enters its first month, police are called out to protect the scab workers (some of them convicts released from prison for the job) Eastover has sent in to work the mine. At this point the strikers are still presenting a united front in the face of Duke Power's blithe willingness to starve them out.

Barbara Kopple came into documentary filmmaking when the genre was entering a wildly creative period in the '60s with directors like Frederick Wiseman, Shirley Clarke, Richard Leacock and D.A. Pennebaker. She assisted Albert and David Maysles on their groundbreaking Salesman (1969) and was part of the antiwar collective that made Winter Soldier (1972), the film that launched the political career of John Kerry.

She began working on a documentary about the revolt of the rank and file in the UMWA against the union's president, W.A. "Tough Tony" Boyle, who was convicted of a conspiracy to murder his political rival, Jock Yablonski, his wife and their daughter. Kopple was a supporter of Arnold Miller, who was elected by the rank and file to replace Boyle, and the section of her film that tells the story of the murders, Boyle's fall and Miller's rise is the most conventional sequence in the picture.

When she arrived in Harlan County, Kopple tried to maintain the façade of objectivity but found herself being shunned by miners who had been told not to talk to her. When she confronted the person behind this blackballing, they told her that no one trusted this bunch of "hippies from New York" and was asked to tell them, in essence, whose side she was on. Being forced to declare her allegiance was the moment when Kopple's film departed significantly from the studious disinterest that was considered the hallmark of a responsible documentary.

Kopple might have gone to Harlan County to film a bit of colour and context for her story about Miller and the revolt in the UMWA, but what she discovered there would be a gift for both her story and the larger political ambitions of a young female filmmaker in the uneasy aftermath of the '60s cultural revolution.

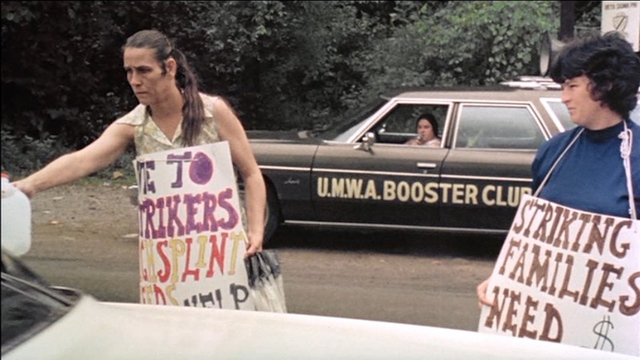

The first thing she encountered was the front and centre involvement of the miners' wives in the picket lines and the resistance to both the police and the "gun thugs" hired by Eastover to break the strike. Reasoning that the strike's outcome will affect them as much as their husbands, the women adopt a more than passive supporting role that was apparently unprecedented but signaled that the social changes of the last ten years and particularly the rise of mainstream feminism had made their way to Appalachia.

Or at least that's the way it might have looked to Kopple, born in New York City and raised in Scarsdale, the daughter of a textile executive and niece of Murray Burnett, co-author of Everybody Comes to Rick's the unproduced play that was made into Casablanca. There had, in fact, always been a strong matriarchal element to poor families in Appalachia, but Kopple was given a gift in the form of Lois Scott, a tough and charismatic miner's wife and de facto leader of the community that organizes behind the strikers.

My memory is that every street in a working-class neighbourhood had a woman like Scott, who could be alternately righteous and terrifying. She calls out the absences of women who had been absent from the picket line and, later in the film when the conflict between the miners and the company is becoming violent, she gleefully pulls a pistol from her brassiere and announces her willingness to use it.

Kopple and her camera spend considerable time with the women of Harlan County during the picture, underscoring how poor wages and dismal safety in the mines – there's a section of the film devoted to showing the effects of black lung and attempts by mining companies to downplay its prevalence and lethality – are a threat not just to the careers of mine workers but to whole communities that rely on their labour to exist where single industries dominate the economy.

The film is scored to a nearly non-stop musical soundtrack of traditional tunes that comment on the action and highlight the themes. Interview subjects will sing, like Florence Reese, author of the union anthem "Whose Side Are You On?", and the miner and folk singer Nimrod Workman. But the tone of Kopple's picture is set by the use of several songs performed by bluegrass singer Hazel Dickens, who wrote and recorded "Black Lung" after the death of her brother.

But Kopple got another gift in Harlan County in the form of Basil Collins, who becomes the film's villain much as Scott is its heroine. A self-described "mine foreman" employed by Eastover, he's the ringleader of the "gun thugs" and point man as the strike becomes increasingly violent as it drags on for months.

With his barrel chest and simian gait, Collins embodies every negative stereotype of the malevolent good old boy, mumbling about how unions are infiltrated by communists and calling a striking miner a "n****r". The scene where the miners arm themselves openly as they wait for Collins and his gun thugs at a roadblock is the most cinematic, and it would have to be recreated if anyone tried to make a dramatic remake of Kopple's picture, right down to an arrest warrant for Collins being delivered to the sheriff.

But the violence that everyone saw coming ultimately arrives and Lawrence Jones, a miner, is killed when a scab shoots him in the face with a shotgun; Kopple even goes to the scene of the crime where a witness points out pieces of Jones' brains on the ground. We see his 16-year-old wife and infant daughter and watch as his mother wails and collapses at his funeral, but Jones' death is bad publicity for Duke Power, who give the miners and Miller's UMWA a contract.

A happy ending, it seems, except the miners have to return to their jobs, which remain as dangerous and miserable as they were before. Hindsight also diminishes this victory, as modern viewers will know that coal mines will join the heavy industries of the rust belt in rapid economic decline very shortly.

But while American industry will be destroyed by the offshoring in the pursuit of shareholder value, coal mining will become a victim of the environmental movement and the pursuit of "clean" energy. In the next decade coal miners would be the heroes of opposition to the government of Margaret Thatcher during the miners' strike of 1984-85, which protested planned pit closures.

A decade later many of the same people who shed tears for the miners and bought Billy Bragg records would be supporting green economic policies that demanded the end of coal as an energy source in Europe (though nobody makes the same demands of countries like China and India). In 2016 Hillary Clinton would make closing coal mines a plank in her green energy transition plan. "We're going to put a lot of coal miners and coal companies out of business," she declared at a town hall campaign stop, a remark she still wouldn't regret as much as "basket of deplorables".

Despite her husband winning Kentucky in 1992 and 1996, Donald Trump took the state with over 62% of the vote in 2016; Harlan County voted for Trump's return to office by 88% in last year's election. While it's no certainty that every rust belt and coal mining district have been transformed into Republican strongholds, they have certainly been enthusiastic in their support for Trump, who has promised not just to return offshored industry but also traditional energy sources to America.

This is good news for Duke Power, which remains in business as Duke Energy, providing electrical power from natural gas, oil and coal, as well as from wind power managed by its renewable energy services subsidiary. But there are no more unionized coal mines doing business in Kentucky, though tourists can visit a coal mine museum at Harlan County's Portal 31 Exhibition Mine and ride a rail car past animatronic exhibits.

We get a glimpse of this unhappy future for the miners at the end of Kopple's movie, when they walk out again to protect their right to trigger wildcat strikes to protest local conditions, and we hear miners complain about being let down by Miller and the UMWA, who seem more interested in working out deals with mine owners. In any case the deal the Brookside miners fought for would end up being folded into a global agreement that wouldn't protect them when their jobs disappeared.

This is consistent with my own memory of union work in my working-class neighbourhood when I was a kid, where everyone dreamed of a union factory job, but every dad and older brother who had one complained about their shop steward and union leadership as much if not more than the bosses or corporate owners. What remains of traditional labour unions are being forced to follow their members and swing their support behind conservative candidates like Trump (and Pierre Poilievre, whose union support still didn't help him win the recent election in Canada).

Powerful public service unions, representing teachers and government workers, have taken the place of the old labour unions standing behind Democrats in the U.S. and progressive parties in Canada and Europe, in a situation nobody could have predicted when Kopple as making her film. (My friend Kathy Shaidle, late of this column and raised in Canada's rust belt capital, was fond of saying that nobody who works indoors needs a union.)

Barbara Kopple would win her second Oscar in 1991 for American Dream, a documentary about a strike at the Hormel meatpacking plant in Austin, Minnesota. She's made documentaries about Woody Allen, Gregory Peck, Mike Tyson, the Dixie Chicks and the generation gap between attendees at the Woodstock festival in 1969 and their more notorious sequels in 1994 and (especially) 1999. But I have a hard time imagining Kopple – or anyone – making a documentary about what remains of the miners of Kentucky today.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.