The career of director Michael Powell was a discovery I made later in life, when I was around thirty and decided to check out a retrospective of his films at the local cinematheque. I became an instant convert and agree with Powell acolytes like Martin Scorsese that he's one of the greats, to be spoken of in the same sentence as Ford, Hitchcock, Hawks, Wilder, Welles and Kurosawa.

For his part Powell was in love with the movies and regarded working as a director as something like a spiritual calling. "The craft is a mystery," he wrote in Million Dollar Movie, his second autobiography. "Nobody can explain it. Writers on film can list the qualities – supreme confidence, endless patience, excessive energy – but they can't explain how those moving, talking images got onto the screen and excited the audience so. Impressionist painting could not have existed before the nineteenth century. There was no need for it, no demand for it. But when it was recognized, it took over. The twentieth century belongs to film."

Writing about the long, slow fade to Powell's career in his introduction to Million Dollar Movie, Scorsese says that Powell was ill-suited to "the cynical of postwar film production, where the pressure to succeed commercially became almost unbearable. Michael lived film as art, and art as his religion. To abandon his cherished creative freedom was impossible; it was like losing sight of the Grail."

It would be easy to celebrate Powell by talking about his most critically lauded, consistently successful, iconic pictures – like The Red Shoes, Black Narcissus, A Matter of Life and Death and The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. All these films contain the hallmarks of a classic collaboration between Powell and his longtime writing and producing partner, Emeric Pressburger. It's more of a challenge to sell Powell to the merely curious with his less successful, more idiosyncratic films (though nearly every Powell film is peculiar at its heart): pictures like Peeping Tom, A Canterbury Tale, Gone to Earth, Tales of Hoffman – and this week's movie, The Small Back Room.

The film was made at a crucial time in Powell's career, just after he and Pressburger were at the peak of their collaboration, after making (in order) 49th Parallel, One of Our Aircraft is Missing, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, A Canterbury Tale, I Know Where I'm Going!, A Matter of Life and Death, Black Narcissus and The Red Shoes. The last film – considered their best by many critics and fans – was anticipated to be a flop by its distributors, the Rank Organization, who had been producing partners with The Archers, as Powell and Pressburger called their company, for the whole of that run of films.

Rank and its notorious managing director, John Davis, were unimpressed with The Red Shoes; as Powell wrote in A Life in Movies, his first autobiography, "The Red Shoes was not to have a London premiere and would go out on general release. This would obviously signal to the whole film business that Rank and Davis didn't believe in The Red Shoes and were rushing it out to get as much money into the box-office before unfavourable audience reaction or criticism killed the picture stone dead. This was war!"

This led Powell and Pressburger to revive their relationship with Alexander Korda, who had worked with the pair on earlier films like The Spy in Black (1939) and The Thief of Baghdad (1940). It's easy to consider the film they made as a stylistic break from the increasingly stylized pictures they'd made with Rank, but you can only do with a cursory glance at The Small Back Room, which is really just a slight retreat from their increasingly exuberant style, and only because it was shot in black and white instead of the saturated Technicolor of their last three films.

Released in 1948, The Small Back Room is set just five years earlier, at the point where World War Two was finally far from lost, but definitely far from over. We follow Capt. Stuart (Michael Gough) through blackout London to Park Lane House, a vast building requisitioned to house agencies representing all the nations and governments in exile fighting the war under the Allied umbrella.

A handwritten sign directs Stuart to a ramshackle outbuilding housing the group working under Professor Mair (Milton Rosmer). He's one of those boffins like Barnes Wallis, inventor of the bouncing bomb (played by Michael Redgrave in the 1955 film The Dam Busters), enlisted by the British Ministry of War to develop weapons and technology to use against their Axis enemies. If this were an American film these scientists would all be in uniform and housed in bright new facilities built in a month by the army.

But this is Britain and Powell does an excellent job showing how these underfunded groups compete for money and attention from their government and military overlords; John le Carre's Smiley books would portray British espionage and intelligence agencies working in similar sordid circumstances, all very far from the fantasy of efficiency and technological excellence in James Bond movies.

Stuart is looking for Sammy Rice (David Farrar), a civilian working for Mair's group, and he's only able to locate him with the help of Susan (Kathleen Byron), Mair's very efficient secretary, who directs Stuart to a pub where Rice drinks until he's cut off by Knucksie the well-intentioned former pugilist barkeep, played by no less than Sid James. Stuart flirts with Susan, who takes a liking to him, though she lets him know that she and Rice live across the hall from each other, which facilitates their low-key romance.

Stuart tells Rice about a top-secret German weapon he's dealing with – a small but intricately booby-trapped bomb that's being dropped at random all over the country, and which has so far detonated before they can find an example to study, claiming a rising number of victims as it does. Rice has a background in bomb disposal that makes Stuart assume he might be interested, and the two men agree to keep in touch with each other until such time as an intact bomb can be found for study.

We're filled in with what we need to know about Rice, principally about his prosthetic foot and the prescription "dope" he takes to unsuccessfully dull the pain. How he lost that foot – the background in bomb disposal suggests an answer – is never explained. We learn that he's a bad drunk, exacerbated by self-loathing and self-pity, who sticks with beer because whiskey makes him particularly belligerent to himself and others.

He is, however, blessed with some brilliance, and his relationship with Susan is both the cause and reward for keeping himself together. He considers himself unworthy, though; he notices how Stuart flirts with Susan and remarks on it without much apparent enmity. He's certain that she could do a lot better than him, though Susan simply explains that she has an intuition that Stuart is the kind of competent and confident man whom Sammy would benefit from knowing.

All of this is deftly painted by Powell and Pressburger's script (based on a novel by writer and psychologist Nigel Balchin), and by excellent performances by Farrar and Byron. The two had appeared together a year earlier in Black Narcissus, Farrar playing Dean, the British agent in India, with Byron giving an indelible performance as Sister Ruth, the emotionally unstable nun driven mad by the climate and her sexual obsession with Dean.

Black Narcissus was a torrid fantasy of the Indian raj, shot at Pinewood studios and in the West Sussex gardens of an Indian army retiree who collected native subcontinental flora. It was also a perfect example of the Powell and Pressburger style – richly detailed to the point of being almost overwhelming, explicit in its cinematic artifice, with an emotional tone best described as simmering on the edge of boiling over.

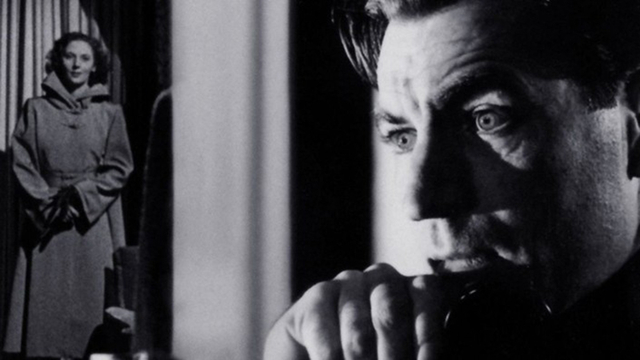

Depriving himself of the saturated Technicolor film he had used to such great effect in his recent pictures, Powell leaned into German expressionist films of the silent era – movies like The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari and Nosferatu – and he began a new collaboration with cinematographer Christopher Challis (Sink the Bismarck!, Two for the Road, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, The Deep, The Riddle of the Sands), who had been a camera assistant on several of the Archers' recent films.

The result is a film full of deep shadows and high contrast lighting that lavishes stunning closeups on its lead characters, with Byron in particular landing in flattering pools of light no matter where she might be. This has given The Small Back Room a reputation as one of the best British contributions to film noir – a psychological thriller full of tension and desperation, highlighted by its wildly dramatic lighting and camera angles.

Byron would be one of the leading ladies that would be both muse and romantic interest for Powell, along with Pamela Brown and Byron's co-star in Black Narcissus, Deborah Kerr. He described her as having "a dreamy voice and great eyes like a lynx", and Byron is one of those striking beauties of British postwar cinema, the ranks of which include Glynis Johns, Valerie Hobson and Joan Greenwood.

Powell would be named as a co-respondent in her 1950 divorce from her USAAF pilot husband; in Million Dollar Movie Powell describes her pulling a gun ("a revolver, a big one, U.S. army issue, and it was loaded") on him during the filming of Black Narcissus: "A naked woman and a loaded gun are persuasive objects, and I have always thought that I deserved congratulations for talking myself out of that one." For her part Byron denied pointing the gun at Powell, but the anecdote has come to sum up their relationship for posterity.

It's a shame that Farrar and Byron were only paired together twice; they're incredibly convincing as a couple in The Small Back Room, suggesting real intimacy and the sorts of shared codes and rituals that hint at co-dependence. This has a sometimes dangerous aspect, embodied in the unopened bottle of Scotch whiskey Rice keeps in a prominent place in his flat. They're saving it "for V-Day" he explains to Stuart, but he and Susan use it to cope with his alcoholism during his dark moments; she pretends to give him permission to open it, and his pained decision to keep it sealed is their sign that the crisis has passed.

Their performance, combined with Powell's direction and Challis' camera, create a claustrophobia that builds as the film goes on, no matter where the scenes take place, from the cramped little rooms of Mair's offices to the Hickory Tree, the night club where Sammy and Susan go to share the desperate gaiety of London night life during the war. (Ted Heath and Kenny Baker's swing group are the house band.)

The low camera angles and multiple levels of the club heighten the sense of being oppressed by the crowds and noise, and the audience is allowed to share Sammy's abiding discomfort. It's assumed that the film's title is a reference to the "back-room boys" who worked secretly on weapons for the war, but it also evokes Rice's cramped furnished rooms, and some critics have gone so far as to suggest that it refers to Sammy's mind as it becomes steadily unsettled.

In addition to the film's main relationship and the subplot involving Stuart's booby-trap bombs, which only becomes important in the last half hour, most of the conflict in The Small Back Room is in Rice's relationship to the politicians, military brass and bureaucrats who control his work. There's one comic scene where a surprise visit by the government minister who oversees Mair's office (played by an uncredited Robert Morley) forces everyone to hastily set up their labs with a collection of parlour tricks that predictably impress the simpleminded buffoon.

Another subplot is the development and testing of the Reeves gun, a piece of anti-tank artillery that we first see being evaluated on proving grounds next to Stonehenge. (The ancient monument was the home to a massive military base during World War One, with an aerodrome built adjacent to the megaliths, and Salisbury Plain has been used as a military training ground for over a century.)

Mair, Sammy's boss, is keen to be involved with the testing and evaluation of the gun, as is Waring, the bureaucrat overseeing Mair's office (played by Jack Hawkins with the kind of unctuous oiliness an ad man would bring to the position), and the bureaucrats at the Ministry of Defense are heavily invested in its success. But the soldiers who have to use the thing doubt it'll be good at anything but increasing their own casualties.

This conflict comes to a head during a darkly comic scene where Rice and Mair present their findings to the new minister and a table full of bureaucrats and brass at Westminster. The minister is blithely disinterested and distracted by a portfolio of prints on the table in front of him, everyone who speaks has to compete with the sound of jackhammers (the House of Commons chamber was bombed by the Luftwaffe in 1941) and Sammy presents the figures on the Reeves gun tests while staff loudly go about blacking out the room.

Powell presents a relentlessly hostile portrait of how bureaucracy and politics are enemies of effectiveness and efficiency so nearly debilitating to the cause of winning the war that they might as well be called treason. It's understandable when you remember how official disapproval of The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp and attempts to halt production and censor the film – coming from no less than Winston Churchill and James Grigg, the war secretary – soured the propagandists in power on The Archers, who were their darlings at the start of the war.

Rice finally snaps under the pressure, which inspires a surreal, theremin-scored dream sequence back in his flat where the bottle of Scotch looms over him; he falls off the wagon spectacularly after breaking it off with Susan. These scenes make claims that The Small Back Room is a sedate retreat, a "step back" from the stylizations of previous Archers films, basically ridiculous. They also suggest (to me) that much of what people claim to see as the genius of Hitchcock are more than abundantly present in Powell's films.

Deep into his bender Sammy tries to ignore the ringing phone, which turns out to be Stuart, calling to tell him that they've found two of the booby trap bombs and that he needs to get there immediately. At its most oppressive moment the film is suddenly allowed to leave the back rooms and go outside, to the bright sun and pebbled beaches at Chesil on the Channel coast.

Rice arrives at the seashore to learn that Stuart was killed trying to defuse the first bomb, which is apparently equipped with not one but two movement sensitive "trembler" triggers. Using the notes dictated by Stuart down a long microphone cable to a corporal in the Auxiliary Territorial Service (Renée Asherson) who was clearly in love with him, he insists on defusing the second bomb.

Keeping the bomb clamped and stable on the pebbled shingle of Chesil is the greatest challenge during the 17-minute sequence where Sammy takes the bomb apart in real time – a scene that Powell fans like to point out is precisely as long as the final, fatal dance by Moira Shearer in The Red Shoes. His success despite the unfavorable conditions and his hangover redeem him – a feat that proves his skill and ability that allows him to return home to Susan and a commission as a major overseeing his own research department.

Looking back at the film in Million Dollar Movie, Powell admits that he understands why the picture was a hit with critics but not audiences in 1948. "The public stayed away. They refused to accept that it was a love story. It was a war film. And war films were out—O-U-T."

He recalls how Noreen Ackland, the assistant editor "declared that the love scenes between David Farrar and Kathleen Byron made the public uncomfortable: 'They're so real. They make you feel like you are spying through at keyhole at the two lovers.'"

In the scene on Chesil Beach, Powell writes, "they see the kind of David Farrar that had been promised them by the sexy Mr. Dean of Black Narcissus. But for most of the film Sammy is a miserable, complaining, self-destructive failure, and the part required more humor and self-mockery to be written into the script to save Sammy from becoming a bore...The more that we admired and used Nigel Balchin's mordant psychology, the less the public liked the film, and although Kathleen Byron played Sue beautifully, the public sensed her intelligence and refused to believe that she would waste so much time of Sammy's agonizing."

Re-watching it again over three decades later at a New York retrospective screening, Powell said that he "found this particular movie a cold one. But in 1948, I needed to tell a love story like The Small Back Room. I needed to escape from romance into reality. I needed to create the kind of woman that I admire, who keeps the world turning without making a song and dance of it. I needed Sue."

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.