It didn’t take long for the US military to retaliate to the drone strike in Jordan that killed three American soldiers. It was always a question of how hard and when, not if, America would strike back. “Our response began today. It will continue at times and places of our choosing,” President Joe Biden said in a statement. Be in no doubt though: the US air strikes, using long-range bombers to hit eighty-five targets in Iraq and Syria, mark a dangerous and unpredictable new phase in the spiraling Middle East conflict, with potentially far-reaching consequences.

The Americans chose their targets carefully enough. They hit four locations in Syria and three in Iraq linked to the Tehran-sponsored militias. The targets included command and control centers, rockets, missiles and drone storage facilities, as well as logistics and munition supply chain facilities, according to US military officials. Also targeted were facilities used by Tehran’s Quds Force — significantly, it is the first time the US has hit the force directly in the region. The Syrian Defense Ministry described the attacks as “blatant air aggression.” Iraq has described the action as a “violation of Iraqi sovereignty” and warned of “dire consequences.” Iran’s foreign ministry condemned the attacks as a violation of international law and said the US was engaging in “another adventurous and strategic error.”

The danger signs are everywhere. The drone strike in Jordan last weekend was a significant escalation in itself — the first deadly attack on US soldiers. It was aimed at provoking an American response, which has duly come. Slowly but surely the Middle East conflict has been growing since the Hamas attack on Israel on October. 7 The Houthi forces in Yemen, also Iranian-backed, have been firing drones and missiles at ships in the Red Sea. The United States and UK have responded with military strikes against the Houthis. The Iranian-backed militia groups will now want to respond to the latest US military action and step up their attacks on US forces in the region. They certainly have plenty of targets: the Americans have some 900 troops in Syria, and around 2,500 troops in Iraq. The US has already been targeted over 160 times in Iraq, Syria and Jordan since the Israel-Hamas war began.

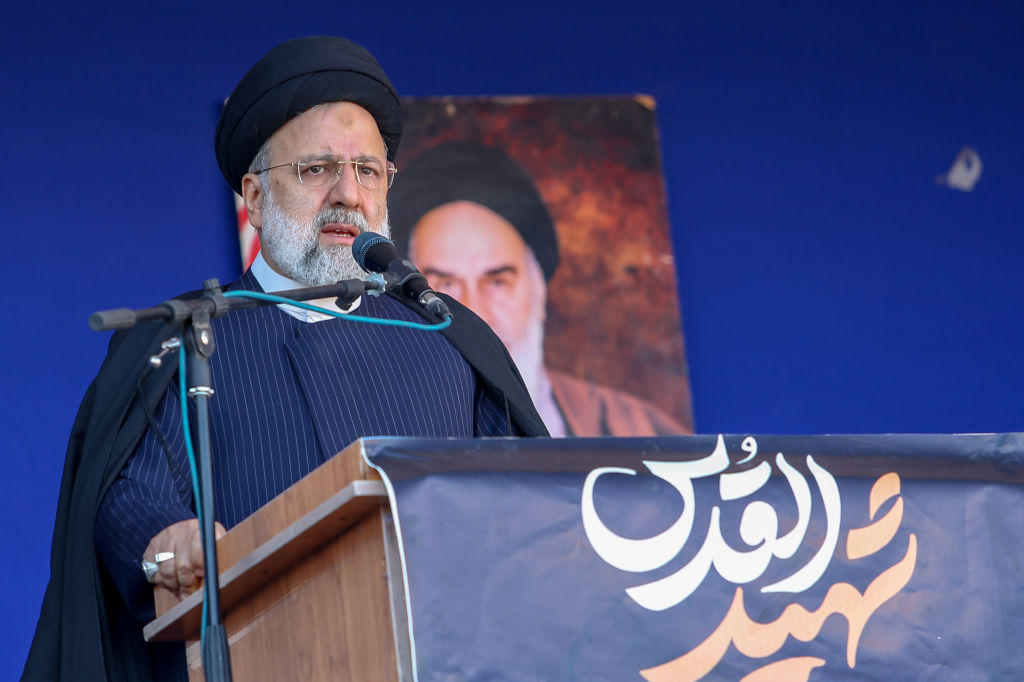

The real worry is of a direct conflict between America and Iran. Both countries insist that a broader confrontation is not on the cards but that does not mean it can be avoided. The Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi has said that Iran would not start a war but would “respond strongly” to anyone who tried to bully it. The Biden administration is seeking to deter Iran without going to war — a delicate balancing act that looks more precarious with each passing day.

Biden is also facing growing pressure back home over his Iran strategy (or more accurately, the lack of one) in what is an election year in America. His likely opponent in that election, the former president Donald Trump, has already accused Biden of being weak on Iran. So too Roger Wicker, the senior Republican on the Senate Armed Services Committee, who criticized Biden of failing to impose a high enough cost on Iran. Biden is in a bind. He wants to signal that attacks on US forces in the Middle East will not be tolerated or go unpunished but do so in a way that doesn’t trigger a wider conflagration across the region. This is why the White House took its time in picking carefully its targets, which significantly did not include any groups based in Iran itself. It was a demonstration of American military strength in a calculated manner.

The question is this: what happens now? More attacks on American forces across the region are inevitable. The US will have to respond in kind. The latest US air strikes — part of a “multi-tiered” response — risk turning into a prolonged American military campaign. In other words, America is being sucked back into the Middle East at a time of raging war, all the while insisting that it seeks no confrontation with Iran, the main source of instability and conflict in the region. How tenable is that?

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.