In ‘Suddenly Something Clicked,’ Walter Murch, Francis Ford Coppola’s Longtime Editor, Decodes the Language of Film

Today, over 130 years later since the invention of the motion picture, whether we watch a film on a big screen in a movie theater, or we sit alone in front of a big screen TV watching a movie on Blu-ray or streaming, we take for granted the format’s symbolic language. Of what cuts, fade outs, dissolves, shot lengths, and differing camera angles signify. But that language all had to be invented, along with, at least for Hollywood’s golden era, a focus on adapting novels to film rather than filming mindless spectacle for its own sake. Walter Murch’s new book, Suddenly Something Clicked, breaks down both the history, as its subtitle implies, of “The Languages of Film Editing and Sound Design,” and how that language affects us when watching a movie.

And the 82-year-old Murch would definitely know. He’s worked as a sound designer on Apocalypse Now and an editor on The Talented Mr. Ripley, winning Academy Awards for Best Sound on Apocalypse Now and both Best Sound and Best Film editing on The English Patient. In 1998, he completely overhauled Touch of Evil, Orson Welles’ last completed film shot in America during his life, but massively interfered with by a heavy-handed Universal Studios because the man who directed Citizen Kane lacked final cut of the film. (Much more on that in a couple of moments, and note that Murch wisely avoided working on Megalopolis, Coppola’s I, Claudius meets The Fountainhead meets 9/11 on LSD megaflopolis from last year.)

The title of Suddenly Something Clicked is explained at the start of Murch’s book, where he writes:

“In late June of 1896 the Lumière brothers brought their cinématographe and reels of moving photographs to Nizhny Novgorod, 400 km east of Moscow. The city’s only available venue was Aumont’s café, an elegant brothel run by the French–Algerian impresario Charles Solomon. A bedsheet was strung up at one end of the central salon and the cinématographe installed at the other, while Nizhny’s great and good (and not-so-great and not-so-good) crowded together to experience something they had never seen before: moving photography, projected onto a bedsheet in a brothel.

Maxim Gorky, then a twenty-eight-year-old reporter (later to become the novelist for whom the city of Nizhny would be renamed), was in the audience taking notes. The cinématographe’s lamp ignited and a still image illuminated the sheet…In his article, published a few days later, Gorky would describe the experience as ‘A Kingdom of Shadows: before your eyes, life is surging, but it is a life deprived of words and shorn of the living spectrum of colours – a grey, soundless, bleak and dismal life.’ Gorky’s remarkable recoil from the miracle of moving photography was an early case of the uncanny valley: that queasy feeling inspired by an image that closely simulates reality but doesn’t go quite far enough, as if the image were, zombie-like, alive and dead at the same time.

But there was something else, which Gorky mentioned only in passing: the instantaneous cut from one shot to the next. He had been watching the Lyonnaise street scene, when...

"... suddenly something clicks, everything vanishes and a train appears on the screen. It speeds straight at you – watch out! It seems as though it will plunge into the darkness in which you sit."

What he had heard – that click – and what he saw – everything vanishes and a train appears – was a splice in the film, jerking the audience instantly 350 km from the streets of Lyon to a station on the Côte d’Azur, where a train was just arriving. This was the first time in history that anyone had written about the phenomenon of the cut from one moving image to another, yet this barely remarked-upon moment was the tiny seed that would grow, like a vigorously spreading, multi-trunked tree, into the only truly new art form of cinema: montage.

As John Podhoretz wrote in a 2018 article titled, “Invasion of the CGI,” the original Hollywood moguls of the early 20th century instinctively knew they would have to largely eschew the Lumiere brothers’ style of spectacle in favor of adapting the works of great novelists onto film. Otherwise, Podhoretz wrote:

Truth to tell, if CGI and all the tools of digital filmmaking had been available as the motion picture became the dominant medium of the first half of the 20th century, realistic cinematic storytelling might never have evolved at all. The ability to thrill and captivate through the creation of alternate worlds and alternate realities is so seductive, both for audiences and moviemakers, that it would have been hard to resist. Indeed, the very earliest surviving films, by the French director Georges Méliès, are dominated not by story but by visual and cinematic tricks. They were made in the 1890s.

The combination of realistic drama, along with the introduction of sound, beginning with 1929’s The Jazz Singer, created the medium of film as we know it today.

Suddenly Something Clicked was published by the venerable British publishing house Faber & Faber. Murch wrote the book during the covid lockdowns, and as one reviewer notes, he had enough material left over for a second book:

This endeavor ultimately ran long and was split into more than a single book. Suddenly Something Clicked is the first stage, covering picture and sound post-production. At 350 pages (plus acknowledgements and index) it’s about 40% of the total material. The subsequent 60% touches on writing, casting, direction, production, cinema aesthetics, and philosophy. It will be published at a later date.

Into the Mystic

In May, the London Times published a preview of Murch’s new book:

If you had to boil down Murch’s philosophy to one statement it would be this: “If you leave certain things incomplete, to just the right degree, most of the audience will complete those ideas for you. The artistry in every department is to know what can be left out.”

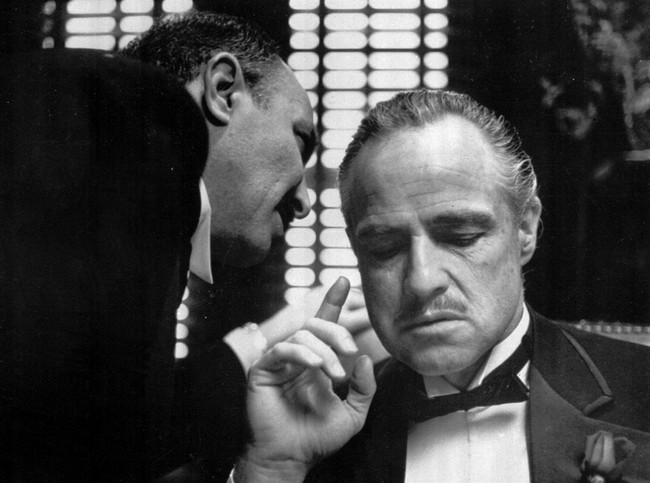

For the 1999 film The Talented Mr Ripley Murch and the director Anthony Minghella opted not to show the film’s climactic murder, instead relaying the sound of it while we observe Ripley’s face reflected in the mirror door of his closet. For The Godfather a cork popping anticipates a gunshot. After 175 tracks of five-speaker surround sound in Apocalypse Now, the compound of Kurtz is noticeable for its eerie silence.

There’s more than a touch of the Vulcan intellectual to Murch. At a drinks party he is the man next to the punch bowl talking about his theories about “squishy ping-pong balls of air”, or Shakespearean iambic pentameter as a rhythmic model for knowing where an editor should make a cut in a scene.

It takes a special type of person to willingly confine themselves to a tiny room where they watch and listen to the same thing over and over again. “This textbook definition of brainwashing pretty accurately describes the daily experience of a film editor,” Murch writes near the end of his new book, Suddenly Something Clicked, a mosaic of observations on his career.

As that passage highlights, at times in Suddenly Something Clicked, Murch aims for the mystical in some of this theories. The London Times noted that Murch's new book “bursts with intelligent chatter, mixing reminiscence and practical tips with metaphysics and neuroscience. Over the course of the book the art of editing is compared to grafting trees, translating books, being part of a jazz quintet, conducting an orchestra, changing gears in a car, bowing a violin, brain surgery, taking off in an aircraft and building a Lego model.”

Editing as a Salvage Operation: Saving The Conversation

Fortunately, in Suddenly Something Clicked, dissertations from Murch on some of his more arcane theories about how the subconscious mind processes viewing a movie are balanced by chapters on his going to work in the editing bay and the dubbing stage. Two of the most enjoyable chapters in Suddenly Something Clicked concern how Murch and his co-editor Richard Chew (who went on to co-edit the first Star Wars movie) salvaged Francis Ford Coppola’s 1974 movie The Conversation, starring the recently deceased Gene Hackman as expert surveillance man Harry Caul. (Given the importance of the film in both Murch and Coppola’s oeuvres, it’s not a coincidence that the cover of Murch’s new book features images of Hackman’s character operating his reel-to-reel tape recorder.) Seen as a smaller, more personal film shot in between the first two epic Godfathers Coppola ran out of time filming it, before Paramount demanded he begin filming The Godfather Part II, leaving, according to Murch, “seventy-eight scenes left unshot,” when Coppola was forced to shut down The Conversation’s production:

I can only imagine what kind of pressure Francis was under, but Paramount certainly considered Godfather Il more important than Conversation.

Nineteen of those seventy-eight unshot scenes were relatively minor ‘connective tissue that had already been judged superfluous. But the other fifty-nine were split between two major sequences: Harry pursuing Ann through a fog-shrouded San Francisco (thirty-five scenes, nos. 282-316); and Harry returning to his warehouse to find it being ransacked by shadowy agents of the Director (twenty-four scenes, 332-55).

The first sequence, involving a slow-motion pursuit between two electric trolley-buses, was intended to be the lead-up to Harry’s personal ‘confession’ to Ann in the foggy park. Without the pursuit, it was not clear how to explain the scene in the park.

The second sequence, crucially, provided the clues to the hidden meaning behind the Union Square conversation itself, showing that the presumed victims, Ann and Mark, were actually the culprits – it was they who ordered their own conversation to be recorded – and that the victim was the Director, whom Harry had assumed to be the culprit.

Without these two sequences, it was not obvious how to resolve the plot of the film, but as Francis left to start work on the pre-production of Godfather II, his advice was to cut the film together the best way I could, and if anything was required to fill the holes left by the unshot scenes, which would almost certainly be the case, he would ask Paramount to release some money for a few days of reshoots.

Richard and I were naturally somewhat spooked by this sudden development – neither of us had edited a feature motion picture before, and now two crucial sequences remained unshot – but we gathered some reassurance from Francis’s relaxed attitude. He seemed to be taking all this in his stride, and given what he had gone through on Godfather, who were we to second-guess the situation?

What follows is perhaps Suddenly Something Clicked’s best chapter, which illustrates how through extremely careful editing and particularly crafty dubbing, a film can be massively reworked, and victory can be snatched from defeat. After a massive editing job, all Murch needed to complete his overhaul was one shot of Gene Hackman’s character discovering that his tapes had been stolen by the mysterious corporation who had hired him for a day’s worth of surveillance recording. As Murch writes, this was shot on a small recreation of the corner of The Conversation’s main set, right next door to another Paramount neo-noir production:

The little set of Harry’s workbench was built in the corner of a stage at Paramount by Alex Tavoularis, Dean Tavoularis’s brother (Dean himself being busy on Godfather II). Gene Hackman was also unavailable, so his brother was hired – it would be an over-the-shoulder shot. Francis was also busy on Godfather II, so I became the designated director. Fortunately, cinematographer Bill Butler was available to recreate the lighting, and he operated the Arriflex ‘B’ camera that we borrowed from the production whose set we had invaded under friendly terms.

The action of the shot was simple: a sudden reaction from Harry after he yanks the take-up reel apart and finds it empty, and then Harry discovering that the boxes of the three original Union Square tapes were also empty.

When we were finished with the third of three takes, the director and the star of our host film came over to see how it was going: they wanted the ‘B’ camera back for their next set-up. It was Roman Polanski and Jack Nicholson – Jack with his nose bandaged up – and, of course, the film was Chinatown. If we had kept the camera running and panned over to Roman and Jack, we would have linked Conversation with Chinatown. A lost opportunity!

Restoring a Director’s Lost Vision: Reediting Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil

One of Murch’s most unusual jobs began in 1998 with a phone call from film preservationist Rick Schmidlin, whom Murch had heretofore never met:

He introduced himself as a Welles aficionado and told me that a couple of years earlier, he had come across some tantalising fragments of the long-lost memo Welles had written. And from that moment on, Rick had made it his mission to locate the entire memo — which, amazingly, he eventually did — and then, equally improbably, to convince Universal Studios to let him start moving ahead with a recut and remix of Touch of Evil, using the memo as a bible. This would be for the fortieth anniversary of the film’s release, in 1998. Rick was looking for someone to take on the interpretive aspects of the project, and he thought of me because he felt I had the necessary expertise in picture editing and sound mixing: Welles’s notes required changes in both areas in equal measure.

In 1958, Universal executives weren't thrilled with Welles directing a movie; Hollywood moguls were happy to employ Welles as a Falstaffian character actor, but by the 1950s, they did not want him behind the camera. But Touch of Evil starred Charlton Heston at the very peak of his career. As Murch notes, he made the film in between starring in The Ten Commandments and Ben Hur. And Heston wanted Welles to be his director. So, Universal’s brass very reluctantly agreed, but unlike Citizen Kane, Welles did not have final cut of Touch of Evil, and once Welles turned in his version, Universal brought in another director to reshoot additional expository scenes, and hired Henry Mancini to record a jazzy Peter Gunn-style score. Peter Gunn, Murch writes, was “a television show starring Craig Stevens as a debonaire detective. Touch of Evil is actually a kind of anti-Gunn: Welles’s [Hank] Quinlan is the opposite of debonaire, eventually plunging to an ignominious death in a trash-choked open sewer.”

Universal was contractually obligated to show their recut version to Welles, but only once. Murch notes that immediately after viewing the film:

Welles quickly typed up fifty-eight pages of comments – astute, insightful, boiling with passion under the surface, but tactfully restrained since he was addressing the heads of the studio (particularly the head of production, Ed Muhl), who were his declared enemies. It is heartbreaking to read, both for the obvious waste of talent and insight of one of the twentieth century’s great filmmakers, and because, with hindsight, we know Touch of Evil was to be Welles’s last film within the Hollywood system.

But it is inspiring as well as heartbreaking. The memo is a unique document that gives us precious insights into Welles’s creative process, insights that we wouldn’t possess if Universal hadn’t taken Touch of Evil away from him. This is the silver lining in an otherwise rather dark cloud that closed around the film in late 1957.

Touch of Evil begins with one of Welles’ most bravura scenes, a three-minute, 20-second long single continuous shot beginning with a bomb being placed in a car trunk, that car being driven past border guards, through the small American border town, past Heston and Janet Leigh, before the bomb goes off. The highly complex scene literally took all night before it was completed to Welles’ satisfaction; the sun was just beginning to rise in the version Welles’ chose to kick off his movie. Directors have continuously borrowed the long take ever since, including Martin Scorsese in Goodfellas, when Ray Liotta and Lorraine Bracco enter the Copacabana, and the opening to Robert Altman’s 1992 film The Player, in which a character in Altman’s long take actually references Touch of Evil, and its underlying synthesized score was clearly inspired by Mancini.

One of the most important changes Murch made to Touch of Evil, following the instructions in Welles’ memo was to remove the opening credits and Mancini’s score from this shot, as they both greatly diminished the tension of the scene; instinctively, audiences correctly assumed the bomb would explode once the credits ended, and knowing the action was occurring under a credit sequence also “kept viewers at a distance from the action,” Murch writes.

With credits and Mancini’s score:

Without:

It’s one thing to salvage the project of a living director who didn’t complete all of his homework, as Murch did for Coppola’s The Conversation. It’s another to rework a film by a late director considered a landmark by some of cinema’s most important filmmakers and critics. Murch writes that "Rick and I were constantly aware of the sacred ground that we were treading in tackling something like this:"

Touch of Evil is an almost holy object for many people, from the members of the French New Wave on. Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut awarded it the grand prize at the Brussels World’s Fair of 1958, and it has influenced several generations of young people to pick up their cameras and microphones and become filmmakers.

In the course of an interview for the LA Times, I mentioned that each decade sees another interpretation of Touch of Evil, and the version that was in the theatres at the time of the piece was Curtis Hanson’s L.A. Confidential. Shortly afterwards, I received the following note from Curtis: ‘Thanks for the mention. There’s no work whose name I’d like paired with L.A. Confidential any more than Touch of Evil. I have the original poster; when I walk up to my office, I see it every day and I bow down before it.’

So when I told friends what I had been up to, they got this shocked and slightly despairing look in their eyes; one of them even said, “You know, this is like hearing that God just phoned and wants changes in the Bible.” But the truth is that Welles was deeply disappointed with the final version of the film (he never saw it again after that one sad screening in November 1957).

Fortunately, Murch’s version works, and is accepted by many as the film’s definitive version. As he quips at the end of the chapter on Touch of Evil, “I hope that when Orson wakes from his nap, he will be reasonably happy with what he sees and hears.”

A playful gesture appears at the bottom of every left-hand page of Suddenly Something Clicked: an aphorism on some aspect of filmmaking or film watching, and at the bottom of the right-hand page the name of the person who created the quote. Murch calls these “fortunes” along the lines of the text found in Chinese fortune cookies and writes:

Each of the 173 fortunes has been selected and calibrated either to amplify the text in the page above it, or to expressly contradict that text (following physicist Niels Bohr’s dictum that ‘every great truth is a truth whose opposite is also a great truth’). Sometimes the link between fortune and text is ambiguous, but ambiguity is often the point – the more obscure and paradoxical these fortunes seem, the truer they probably are, since much about cinema is still so mysterious.

There are also “occasional QR codes dropped in alongside the text…which will take the reader to examples or further explanations of the points I am making (most smartphones have a QR reader built into the camera).” Hopefully linkrot won’t render these online examples obsolete too quickly.

As the Times posits, “Suddenly Something Clicked is more like the director’s cut of” The Conversations, his 2004 book with Michael Ondaatje, the director of The English Patient. But by and large, for both budding filmmakers (including those leaning heavily into AI-crafted video) and serious cineastes, this is a brilliant if occasionally heady read by a master craftsman, as likely will be its planned second volume. Judging by the poor quality of most of Hollywood’s current output, the next generation of filmmakers will need all the help and knowledge they can lay their hands on if they hope to connect with audiences.