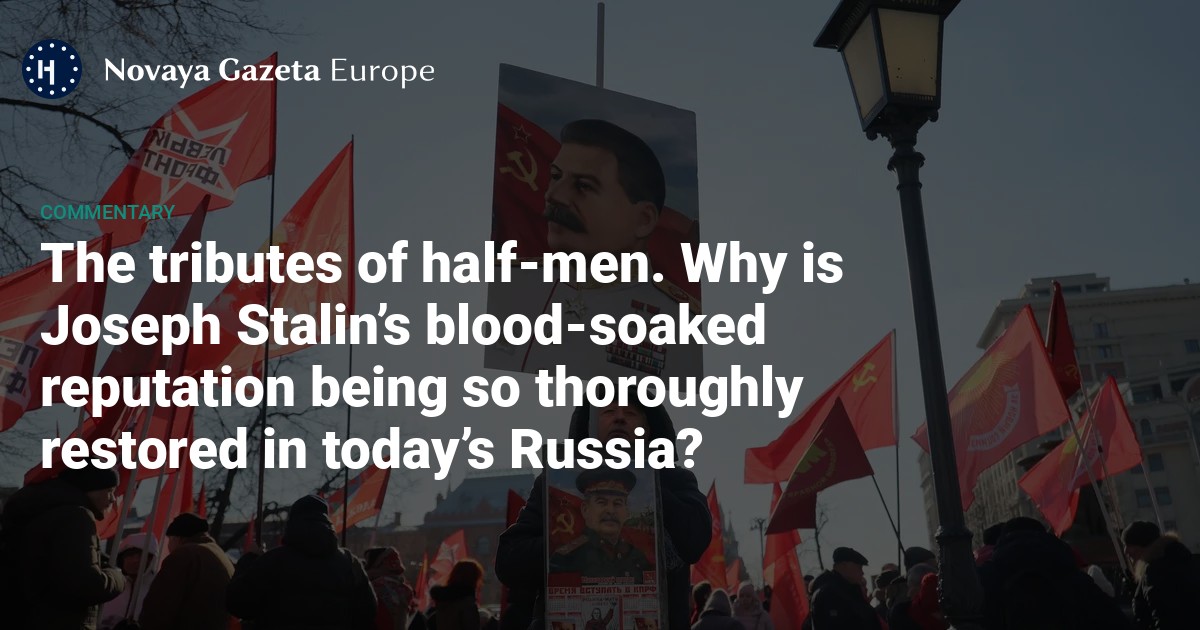

Last September, a bust of Joseph Stalin, one of the greatest mass murderers in history, was unveiled in Volgograd, the southern Russian city that for over 30 years bore his name.

Two months later, another monument to the Soviet dictator was unveiled in Nakhodka, in Russia’s Far East, while in a town in the central Nizhny Novgorod region, the construction of a Stalin Centre to honour the life of the increasingly lionised despot, continued apace. In April, the Urals city of Perm held a Stalin-themed half-marathon, during which participants competed carrying his portrait, and Volgograd’s international airport was briefly renamed Stalingrad International Airport. Most alarmingly, however, was last month’s unveiling of a giant bas-relief prominently featuring Stalin that had originally been removed during destalinisation in 1966, in the vestibule of Moscow’s Taganskaya metro station.

Why is the former Soviet dictator enjoying such a wave of popularity across Russia at the moment? Is it true, as one legislator declared at the grand opening of a Stalin Centre in the southern Siberian city of Barnaul, that Stalin continues to “live” in each and every Russian?

A replica of a sculpture of Joseph Stalin at the Taganskaya metro station in Moscow, Russia, 15 May 2025. Photo: EPA-EFE/MAXIM SHIPENKOV

I genuinely do think that Stalin lives in the hearts of some people in Russia — their cult-like adoration for the dictator is a reflection of both the positive spin the Kremlin has put on his image in recent years, and an echo of the widespread political indoctrination much of the population underwent under his rule.

In early March 1953, for example, when legendary Soviet radio broadcaster Yury Levitan announced the news of Stalin’s death, a flood of letters poured into the Kremlin, which can still be accessed in official Russian archives. In them, the authors express their personal grief at Stalin’s demise, with some even saying they would be willing to give up their own lives to bring about his resurrection.

Those who had grown up without parents — many of them as a direct result of Stalin’s vast and indiscriminate purges — wrote letters expressing gratitude to the late leader for his hard work “raising orphaned children”. In one letter, a woman referred to the Soviet people as “Stalin’s pets” who would always remember their father. In others, the authors described themselves as mere “cogs” in the larger machine of state, stressing their own insignificance relative to the Soviet leadership and, above all, to Stalin himself.

There were of course those in the USSR who rejoiced at the news of Stalin’s death.

Back then, to paraphrase the Barnaul deputy, it really did seem that Stalin lived in everyone. Even prisoners banished to what Solzhenitsyn termed the Gulag Archipelago, the vast network of Stalin’s brutal prison camps, famously wept upon hearing the news, apparently able to forgive the motherland and its leader the “errors” that had wrecked so many innocent lives.

In a letter to the Soviet leadership, one gulag inmate who was later amnestied wrote: “Maybe we did wrong, disobeyed, and mother punished us. But can you hate a mother for that? She has punished, she will forgive and she will caress her children again! That’s how everyone feels.”

Indeed, there was such popular love for Stalin that even after the contents of Nikita Khrushchev’s 1956 secret speech were made public, in which he criticised the dictator’s “cult of personality” and exposed the monstrous scale of his violent repressions, many simply did not believe the claims to be true.

After copies of Khrushchev’s speech were circulated and read aloud in schools, factories and other workplaces, the Kremlin received another tidal wave of letters, this time attacking Stalin’s erstwhile comrades for tarnishing the name of their beloved leader. “Can’t you see what a mistake your comrades are making by denigrating the bright memory of Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin?”, one asked.

Another letter was addressed to Khrushchev personally: “You are destroying the party… You want to pour out all your bile on Comrade Stalin. You are a malicious creature. Lenin educated us, and Stalin reared us, not you. You ordered all communists to read the secret letter. They read it with pain in their hearts.”

A third called on Soviet Foreign Secretary Vyacheslav Molotov to restore order to the party and end the rule of the “careerist” Khrushchev: “After all, you know Stalin and his deeds personally, and you cannot, you do not have the moral right to remain silent, not to protest loudly against the posthumous dirty and false insults of your former comrade in arms.”

It’s therefore likely we’ll see further displays of public veneration for the ghoulish dictator in the near future.

There were of course those in the USSR who rejoiced at the news of Stalin’s death. In the Russian Federation’s official government archive, criminal reports can be found from 1953 that detail how a brave few made a mockery of the USSR-wide mourning period for the so-called “father of nations”.

According to the archives, the day after Stalin’s death, a cinemagoer watching a Soviet propaganda film in Turkmenistan was arrested after shouting out “Hooray for the death of Stalin!” when Stalin’s face appeared on the screen.

Harsh punishments were even meted out to schoolchildren in some cases, such as that of a seventh-grade girl in the Ukrainian city of Lviv, who was denounced by her classmates for saying “That’s where he belongs” during a rally to mark Stalin’s death. The girl was interrogated and sentenced to 10 years of correctional labour.

The opening of the exhibition Yalta 1945 at the Victory Museum in Moscow. Photo: Yaroslav Chingaev / Moskva agency

But considering that even those who personally suffered from Stalin’s actions continued to insist on his ultimate moral goodness in the years after his death, it’s hardly surprising that Russian officials continue to make political capital by praising the dictator.

Historical memory in Russia is now more distorted than ever. Until recently, at least, Memorial, one of the oldest human rights organisations in Russia, diligently upheld the tradition of remembering the victims of Stalin’s monstrous crimes each year, despite a rapidly shrinking official tolerance for dissent in the country.

Since the organisation was forced to end its operations in Russia by the Supreme Court in 2021, however, Russia has drifted ever further towards mythologising and romanticising the darkest parts of its own recent history. It’s therefore likely we’ll see further displays of public veneration for the ghoulish dictator in the near future — after all, he continues to live in many Russians whether they like it or not.

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]

VPNovaya

Help Russians and Belarusians Access the Truth