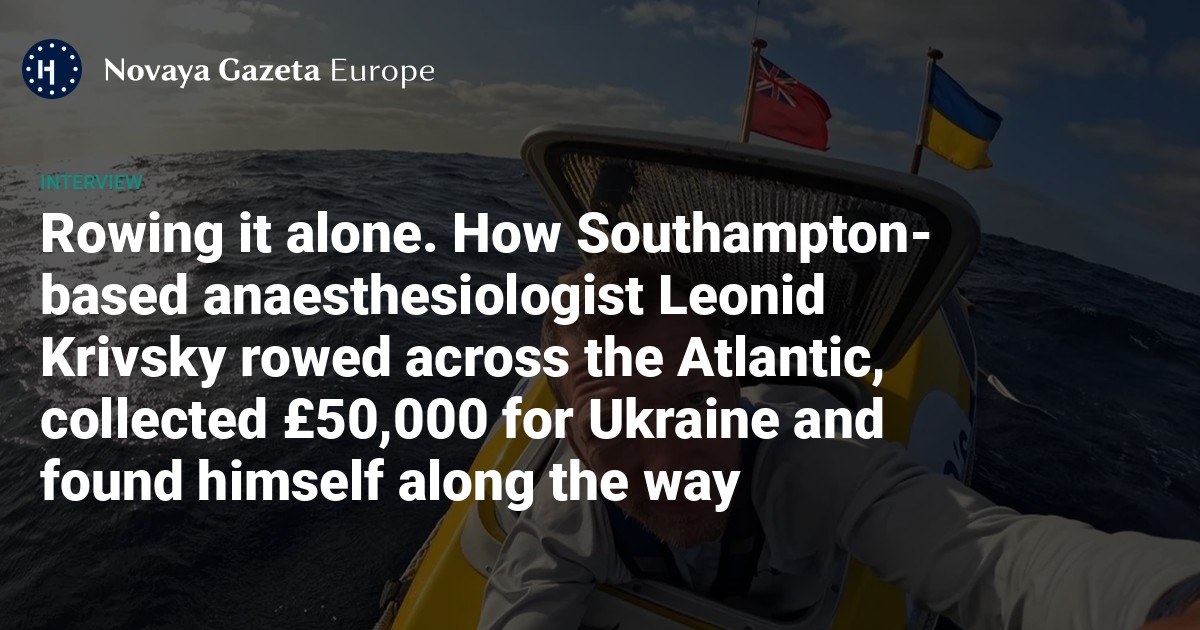

On 26 December 2024, a small rowboat set off from the island of Gran Canaria, heading out into the ocean at a measured pace. At the helm sat Leonid Krivsky, an anaesthesiologist living in Southampton, who had resolved to go a little bit further than the sailboats and fishermen in the water that day — across the Atlantic to Barbados, all by himself.

Dr. Krivsky had a couple of goals. First and foremost, to raise money for Ukrainian doctors — a personal mission of his since the start of the war, for which he founded Ukrops, a medical equipment and supplies charity. And at the same time, to find out what he was made of; to challenge himself via an ocean journey of mighty proportions.

“Don’t write something like ‘Russian doctor helps Ukrainians’. I don’t want to be part of that kind of narrative,” Krivsky tells me.

NGE: To set sail on a rowing journey, across the ocean, alone, and staying alive; that’s a challenge like no other. And something, presumably, for which you need to either train for many years or wake up one day and decide upon without fully thinking it through. Are you a professional rower?

LK: I never had any connection to rowing in my life, unless you count a little bit I did when I was a child. When I turned 50, I was thinking about how to celebrate my birthday differently. I didn’t want to go parachuting; it’s not that fun. You jump, you fly, you touch down, you break your leg, and that’s that. Trust me, I have a lot of parachutists as patients.

Then I came across a rowing ad, some sort of notice for a trip being planned across the Mediterranean Sea. It was being put together by a charity that arranged similar expeditions annually. You sign up, raise £10,000 (€11,900) for the organisation, and then the rest would be organised for you. I foolishly registered and got the money together, and, before long, five of us — completely unacquainted — were put in a boat together and told, “Row!”

NGE: What was that first trip’s route?

LK: Barcelona to Ibiza. After doing it, you could say that I felt an acute sense of hatred that quickly turned into love — I guess those feelings aren’t opposites, one extreme grew into the other. I gradually realised I’d enjoyed it, and this feeling started to grow that I would eventually row further, all the way across the ocean.

“Two topics kept crossing my mind: Ukraine and rowing.”

NGE: So was it the war in Ukraine that finally made you cross the Atlantic?

LK: Not right away, actually. First, I got very involved in collecting humanitarian aid — I would raise money and bring it to Ukraine. And amidst all that horror, I wanted to have something good in my life, even a little drop of optimism. I had an idea to sail across the ocean with Ukrainian veterans or medics; it was a crazy idea, but heartening. Two topics kept crossing my mind: Ukraine and rowing.

Leonid Krivsky. Photo from personal archive

NGE: How long did you expect it to take?

LK: I had enough food for 100 days. And 100 days was the slowest crossing I’d ever heard of. I met the guy who did it, this ex-Special Forces type who hadn’t trained for a solo trip at all. A close friend of his had died, who said before his death that there are some things you just can’t prepare for. So he took those words to heart and went into the crossing with that mindset — he jumped in a boat and just went.

Every journey like that seems to carry a deeply personal meaning. If you row across the Atlantic, nobody’s interested in exactly how you did it, what boat, what equipment and so forth. The only important thing is what it meant personally. It’s hard to explain but that’s the way it is.

NGE: Did you have some sort of motor just in case? What if you’d gotten sick or something else messed you up and you were unable to row? Surely in that case you needed to have an alternative plan.

LK: There was no engine on the boat. If things went wrong and I couldn’t row, I would’ve just drifted. I drifted at night as it was. If winds were blowing westward, I’d make it 10 nautical miles in a night. But when it was blowing in the opposite direction, I’d have to throw a kind of floating anchor overboard, a parachute on a 100-metre rope that would attach to the boat. Before I made it to Barbados, when there was a big storm and the winds were blowing me northwards, I had to use that anchor for six days before everything calmed down again.

NGE: Were there times when you drifted in the wrong direction at night?

LK: Sure there were, whenever I was too lazy to drop the anchor because it would take an hour to deploy it and another to drag it back on board. Right when I started, I had a few good days in good conditions, and then a southerly wind began to push me north. During the day I’d try to row west and it was hard going as I kept getting pushed sideways; I’d be working the left side and my keel kept turning to the right. It was quite difficult. I kept being pushed sideways and I tore my triceps, then tore all the ropes that had held my keel. I had to repair those multiple times. I was still rowing, maybe making a measly 10 miles in the day, and at night I’d drop anchor. Then once I got lazy and didn’t anchor. And I was carried so far north it took me the entire next day to get back on track to where I was supposed to be. On approach to Barbados, the same thing happened. There are a load of local currents there which constantly flow in different directions. On the morning of the last day, I realised that I’d been swept 10 miles south overnight… That’s not a nice feeling!

“Twice I called in and said, ‘I want to stop all this, SOS!’”

Photo from personal archive

NGE: How many weeks in were you before you found yourself thinking, ‘Why did I get myself into this?’

LK: That was part of my thinking every day. Twice I called in and said, ‘I want to stop all this, SOS!’ Once was at the beginning of the crossing. You see, in my field of anaesthesia, if anything happens at the start of the process, the patient is woken up and the operation is halted, and that’s the approach that I wanted to take while rowing. I had some serious problems with steering for the first two weeks and I wasn’t sure if I would make it. I’d call my team and say I didn’t want to continue, but they always just said, ‘Wait, think things over’. If my life wasn’t in danger, if my boat wasn’t sinking, they’d remind me that I’d have to pay tens of thousands of pounds to some shipping company to come pick me up. And I’d take some time to think. Nobody else was there to decide whether it was too hard to continue, just me. But once I solved the first few issues — using common sense, I’m no professional oarsman — I gained confidence.

NGE: But you had been training before you went out onto the ocean, right? It must be hard work physically, rowing 12 hours a day.

LK: Everyone thinks that, but it’s both true and false. It’s not like rowing on a river. You’re more in control of the boat. You’re pushed around, and yet you have to follow a certain direction on the compass. That’s what the oars are for. Yes, during a storm it’s different, but under normal conditions it’s like walking while carrying weights. I could cope with three to four hours of rowing at a time. I didn’t have a schedule to keep to and could take a break at any time. You need to eat every two hours, get glucose, because you expend so much energy and are always low on it. On average, you use between 8,000 and 10,000 thousand calories a day during the crossing.

One time my cabin flooded. I had a lot of snacks under my mattress, which all got wet and went bad. For the last two weeks, I had no snacks at all, and I was seriously lacking in energy. I started hallucinating. My GPS was showing completely different numbers, as if I was going backwards. I was seeing ships, like a ship suddenly appearing on the waves, in detail. Not like some phantom ship. Real ones, just not where they should be. On the whole, I was in pretty critical condition for the last three weeks. It was just totally bleak. Picture the scene. I’m very weak, in a severe storm and 40-degree heat, and I spent a week at anchor. At times like those, I got scared. Not that I’d die. I just thought I’d become an ocean monster that would be stuck there forever and that the ocean wouldn’t let me go, that I was just another sea creature now.

The interior of Krivsky’s boat. Photo from personal archive

NGE: How did you deal with that fear?

LK: My routine was what saved me. I had to row 12 hours a day, and in the last month, that went up to 14 hours. No matter what happened, I just rowed and by the end of the day I felt satisfied. At the end of each day, when I took off my life jacket, I told myself that I had won another battle. And that tomorrow I would do the same. And I never looked more than one day ahead. At some point, I began to think of the ocean as a living creature and I talked to it. I would say to it: ‘You know you’re going to have to kill me if you want to beat me.’ I shouldn’t have said that, because it did try to kill me several times. There were some very difficult occasions. I was thrown overboard, but I managed to hold on by some miracle. You’re strapped in the whole time, but if you go overboard in 10-metre waves, it’s very difficult to get back into the boat.

NGE: Did you cry at any point during the crossing?

LK: In the beginning, I used to well up at the beauty around me. I was in the middle of something perfect. A perfect sky, a perfect ocean, a perfect boat. Even the music was perfect, but my speakers packed in pretty quickly. There was this incredible feeling of happiness. And towards the end, in the last three weeks, I cried in despair three times when I realised I didn’t have the strength to fight on.

NGE: Leonid, how did you manage to get those months off work? Did you just say, ‘Ciao, guys, I’m off?’ And everyone agreed?

LK: Yes, that’s pretty much how it was. ‘Ciao, guys,’ and off I went. My work schedule is flexible. I have to work a certain number of days a year. I can take leave, and then work a bit more at other times. I planned to be away for two months. But the longer I spent out on the ocean, the more worried I got. Catching up on four months, not two, would be a totally different story. But when I got back, I found out my colleagues had stood in for me. They went in to work on their days off. They did two months of work for me. So now I have nothing to worry about.

NGE: How much money did you raise for your Ukrainian colleagues?

LK: It’s over £50,000 (€59,500) now.

Leonid Krivsky after ending his journey. Photo from personal archive

NGE: How did you make that happen?

LK: A lot of people in the UK do things for charity. It’s normal here. You can sign up with some organisation, and it will do the publicity for you. Check out this guy raising money for us. The only thing I had, though, was my own registered charity, Ukrops. It all started with me writing a letter to my hospital colleagues at the start of the war. I didn’t know what I was going to do, but I really wanted to do something for Ukrainian doctors. I’d literally raised £30,000 (€35,600) within a week. My colleagues just kept giving me money. I bought equipment, compression bands, bandages. A friend gave me a van, and I took it all to Ukraine. Then the medical community in that region [of Ukraine] found out about me, and then that happened in the UK too, and medical companies began donating supplies and equipment. And when I decided to row across the Atlantic, word got out. There were media articles, mainly along the lines of “Russian doctor helps Ukraine”. I didn’t like that, but it helped with fundraising.

“For years I’ve been trying to squeeze that imperial mindset and everything Russia-related out of myself.”

NGE: Why didn’t you like it?

LK: Well, I’m 53 now and I’ve lived half my life abroad. I’ve been living in the UK for 24 years. I feel dissociated from Russia. It doesn’t feel close. For years I’ve been trying to squeeze that imperial mindset and everything Russia-related out of myself.

NGE: You mentioned being in a bleak situation, experiencing very difficult moments. If you’d been able to predict those ahead of time, would you still have made the crossing, do you think?

LK: I partly decided to row across the ocean to know who I really am and what I’m made of. I live a very comfortable life, and I needed to test myself and banish some demons. I’m grateful to have had the experience, even though it was very hard. I didn’t realise it would be as hard as it was. But it was also really interesting, doing it with no experience, without using other people’s planning, looking for solutions to problems on my own. Like when I was anchored for six days in unbearable heat, I told myself that the hardest time was the five hours between noon and 5pm. That made it easier to deal with, psychologically. You haven’t got another unbearable day to get through, just five unbearable hours.

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]

VPNovaya

Help Russians and Belarusians Access the Truth