According to figures published by the state-run Russian Public Opinion Research Centre, Russian parents spend an average of €530 per year on school uniforms, backpacks, stationery, and other standard supplies needed by their children for their return to school. For LGBTQ+ parents, however, those costs extend far beyond school supplies, forced as they often are to educate their children privately in the face of risks that heterosexual families would rarely even consider.

“I was really worried about having to enrol my son in school for the first time during such a difficult period,” says Natalia, who recalls quickly realising that it wouldn’t be an option when the teacher immediately seemed to brand her a “liberal” and an ideological enemy during her attempt to sign her 6-year-old up for primary school in 2022. A rug featuring a portrait of Vladimir Putin hung on the wall, and every Monday first graders were required to line up for a flag-raising ceremony.

“It’s very hard for me to pay for school. But I don’t see any other way out, unfortunately.”

At that point, Natalia took the tough decision to enrol her son in a private school instead. Even though the school offered her a discount on its fees, the cost was still significant. “It’s very hard for me to pay for school. But I don’t see any other way out, unfortunately,” she admits.

During their first meeting with the school principal, Natalia and her partner were frank about the fact that their son had two mothers, to which they received a calm and matter-of-fact reaction — “Absolutely”.

Since switching schools, Natalia has no longer felt forced to hide the details of her son’s home life when she speaks with his teachers. But that peace of mind came at a steep price, with private school tuition starting at around 55,000 rubles (€560) per month and reaching upwards of 100,000 rubles (€1,019).

Neither teachers nor other parents have so far asked questions or treated Natalia’s family any differently, she says, and yet as she enrols her son in each successive grade, Natalia admits to experiencing renewed fear that some of the other parents might react with hostility or begin to ask uncomfortable questions. In today’s climate of repression, she says, nobody feels entirely safe.

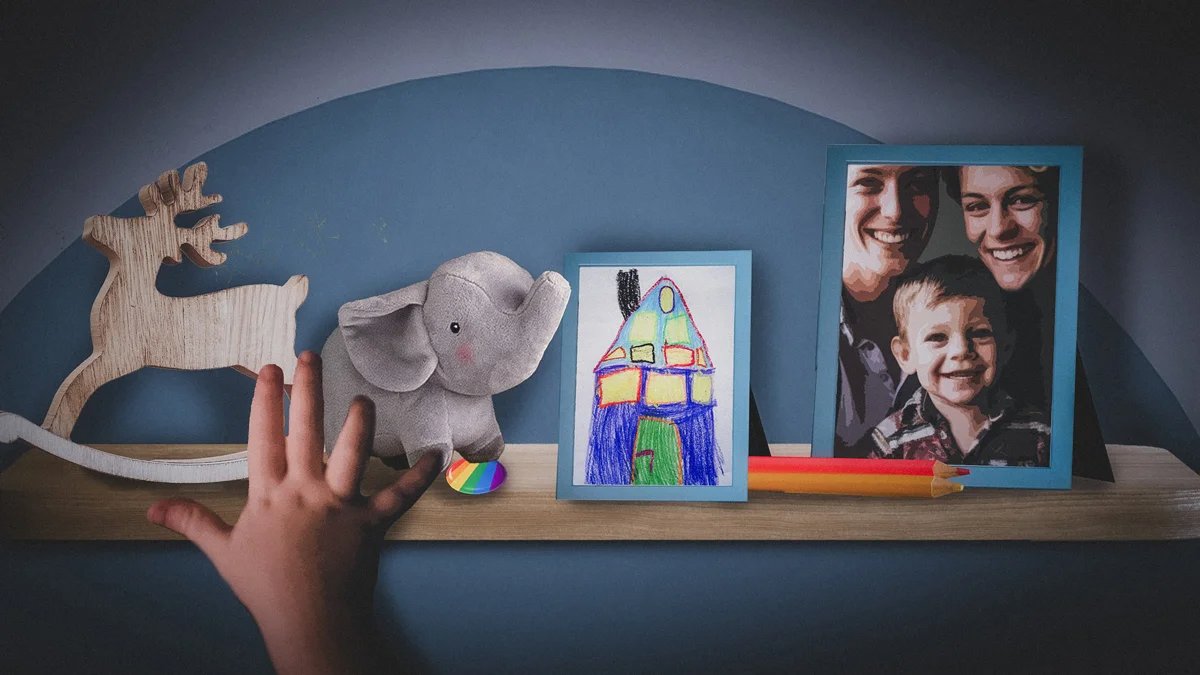

Illustration: Novaya Gazeta Europe

For other queer families, the path to safety lies through emigration. Following Russia’s full-invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Lyudmila left Russia with her wife and two children. Before their departure, they lived in Moscow where they had long attempted to avoid interacting with state institutions whenever possible.

Even before they emigrated, Lyudmila and her wife deliberately kept their children out of public nursery schools, paid for private health insurance, and enroled their daughter in a private primary school. “You have no rights at all,” Lyudmila says of a non-biological parent’s legal status in Russia.

Queer partners simply cannot be recognised as a parent under Russian law, forcing families to build their lives around bureaucracy. For example, only a legal parent or guardian is allowed to pick up a child from school; an unrelated adult would need legal power of attorney to do so.

Lyudmila says that she didn’t even attempt to test those rules, and that they chose a private school from the start, as things were simpler there. “If the school is private, you can just list whoever you want as a trusted adult, and that person can pick the child up. With kindergartens, though, it’s not quite that easy,” she explains.

At public nurseries, staff would probe: “Who is this? A grandmother? Someone else?”

At public nurseries, staff would probe: “Who is this? A grandmother? Someone else?” Though they may not always have demanded documents, Lyudmila says that she nevertheless felt an irritating pressure to justify herself and to prove that she had a right to collect her own son.

By contrast, the atmosphere at private nursery schools was far more relaxed: there were fewer members of staff, and they were much more reasonable, having been informed in advance by the administrators about their family structure. Lyudmila was upfront with the principal: “Our daughter has two mothers. If that’s going to be a problem at your school, then, well, we won’t come,” to which she received the calm assurance: “No, that won’t be a problem at all.”

Once again, that sense of safety came at a steep cost, and Lyudmila doesn’t mince her words about the financial strain it places on her family: “We paid a hell of a lot for everything,” she says.

With two kids in private nursery school, the family was spending over €1,000 per month on education alone, excluding healthcare. Given that those figures were from 2019–2021, doing so today would be even more expensive, she says.

Illustration: Novaya Gazeta Europe

Vera is a queer mother of two children aged 14 and 16 years old, whom, until 2023, she raised with her partner in a small Russian town. She recalls having to drill into them both that they were under no circumstances to mention their home life at school, and that if her partner came with her to pick up her children, Vera would introduce her as “a friend.”

That forced secrecy felt necessary: after the law banning so-called “LGBT propaganda” was passed, Vera seriously feared that being open about her identity could cause problems for her kids, not least as they were attending a state school.

“I tried not to be too visible or too active, so as not to attract unnecessary attention.”

Vera has always been guided by strong convictions and a keen awareness of injustice: she is an activist at heart. Suppressing that side of herself for her family’s safety was painful. “I tried not to be too visible or too active, so as not to attract unnecessary attention,” she admits, worried that taking an outspoken stance on any issue could result in unwelcome scrutiny of her private life.

Her children, too, learned the rules of concealment early. They had joined her at anti-government protests before the war, so by 2022 they already understood that their family’s anti-war views were not to be voiced in public. Once, Vera overheard her son discussing the war at school with a classmate who had used a common slur for Ukrainians. She immediately stepped in to shut it down: “Dima, we’re not going to talk about this topic.”

“My kids are already the children of a dissident,” she says half-jokingly, adding that doublethink had long been second nature to them. Ultimately, with pressure mounting, Vera decided it would be safer to leave the country, and so in 2023, she and her children emigrated.

Illustration: Novaya Gazeta Europe

Even after moving to Europe, Lyudmila’s habitual secrecy didn’t disappear overnight. She and her family settled in one of the Baltic states, where her marriage to her wife, which was registered in Denmark, is legally recognised. However, when they return to Russia they still take precautions. “We mostly stay at the dacha, we don’t really go anywhere,” she says, adding that if they do go into town, the children are instructed to refer only to their biological mother as “mum.”

With their younger son, they don’t try to enforce a strict ban on talking about the family: it’s easier, Lyudmila explains, to tell others that her “auntie” is actually the godmother than to force a preschooler to lie and live in constant fear of slipping up. Their 11-year-old daughter, however, already understands on her own: “She understands that she shouldn’t say anything,” Lyudmila says.

“When we cross into Russia, we do it in pairs, one adult with one child. My wife and I are paranoid that they could take the kids away.”

Fear, she notes, is a constant companion for queer parents in Russia. “The scariest thing is that for some reason they could take the kids away,” she says. Legally, it’s tricky for the state to strip a parent of custody for being homosexual, but amid the state’s homophobic campaign, families live with a pervasive, irrational dread that it could happen. To minimise the risk, Lyudmila avoids spending too much time in Moscow and refrains from going out in public with her wife and children.

Even crossing the border becomes a source of anxiety: “When we cross into Russia, we do it in pairs, one adult with one child. My wife and I are paranoid that they could take the kids away.”

Meeting the parents of her children’s new classmates is especially fraught. “The chance of running into a homophobe is pretty low, but it’s never zero,” she reflects on her current social circle in exile. In Lithuania, she notes, most of the Russian-speaking community now consists of people with certain views, many of them migrants from Russia, Belarus, or Ukraine, so the likelihood of encountering someone openly hostile is small. Still, total peace of mind remains out of reach: even at a parent-teacher meeting abroad, Lyudmila catches the occasional extra glance in her direction.

Illustration: Novaya Gazeta Europe

Psychologist Mira Kolicheva, who works with trauma in the project Cheers Queers, stresses that the heaviest burden for children in such families does not stem from their queer parents themselves, but from the need to hide the “non-normative” nature of their families. “It’s not because the parents are queer, but because they’re forced to conceal it,” she stresses.

“The child is completely a hostage of the situation,” Kolicheva explains. The constant need to pretend and keep quiet can make a child feel as if there is something deeply wrong with them that must be hidden.

Such feelings can weaken a child’s sense of trust in themselves, in the world, and even in their parents, since they too are complicit in making the child participate in the cover-up. Not every case leads to tragedy: some children grow up to process what happened, understand why it was necessary, and eventually find communities where they can speak openly. But, Kolicheva warns, the long-term tension can still leave a lingering, if subtle, scar.

“You’ll never forgive yourself if your child suffers because of your identity. It’s this stupid feeling that it’s all your fault.”

Another issue these families face is isolation and invisibility. Masho Müller, a lesbian mother of two and parenting doula who helps mothers cope with stress, describes the experience as feeling that “no one else like you exists. We all hide, ‘I’m a lesbian and I have kids.’ is not written on our foreheads” As a result, queer mothers often struggle to find one another and feel crushing loneliness. “There’s no one to talk to, no one to share the experience with,” Müller says.

She is open about another truth: “Many queer parents don’t want their kids to be queer, simply because it’s so frightening and so hard.”

Among her friends, lesbian mothers raising children, one refrain is constant: “we hope our children will grow up heterosexual, because life will be easier for them”. As long as society remains unwilling to accept and protect queer families, parents find themselves building fortresses within fortresses and still feeling guilty. “You’ll never forgive yourself if your child suffers because of your identity. It’s this stupid feeling that it’s all your fault,” Müller explains. Though, of course, the real blame lies with systemic homophobia.

Natalia, Lyudmila, Masho, and the other women who shared their stories want only one thing: for their children to be able to study and grow up in safety. Their kids already know they have two mothers. Now, it’s the rest of the world that needs to understand and accept it. As one of them put it: “If you feel like condemning queer parents, it’s better to keep quiet. And if you can’t support or help them, then just leave them alone.”

*All names in this article have been changed for safety reasons.

Tatyana Kalinina is a women’s and queer rights activist and the founder of Cheers Queers, a community uniting Russian-speaking lesbians worldwide.

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]

VPNovaya

Help Russians and Belarusians Access the Truth