Though she didn’t know it at the time, when the 24-year-old Joanna Fields joined a group going on an organised tour of the Soviet Union in 1984, the journey would mark the start of her lifelong association with Russia and a profound kinship with the emerging superstars of the Leningrad musical underground.

After a fortuitous meeting with Akvarium lead singer Boris Grebenshchikov on that first visit, Fields became something of a lifeline for the incendiary talents of the burgeoning Soviet rock subculture, whose brightest lights were increasingly finding themselves suffocated by official attempts to prevent their performances in the dying days of communism.

In the years to come, she would end up smuggling Akvarium’s records, as well as those by iconic Soviet rock group Kino, into America, and illegally importing instruments into the USSR, including a Fender Stratocaster guitar purchased by David Bowie as a present for the already legendary Grebenshchikov. She would also produce the album Red Wave in the US, allowing Americans to hear the voices of Grebenshchikov and Kino lead singer Viktor Tsoi for the first time, and bringing both groups vital international fame that would eventually allow them to perform at venues all over the USSR.

Suspected by both the KGB and the CIA of being a spy, when she was refused a Soviet visa, throwing her plans to marry Kino guitarist Yury Kasparyan into disarray, she eventually managed to enter the country by changing her surname to Stingray, allowing her to get a new passport to throw off the KGB.

Thanks to her new identity, she was able to slip into Leningrad for eight hours as a passenger on a cruise ship, taking advantage of a loophole that granted cruise passengers visa-free access to the city. So extraordinary were those years of her life that Bowie at one point wanted to buy the rights to her story and planned to make a film of it in which he would play Grebenshchikov himself.

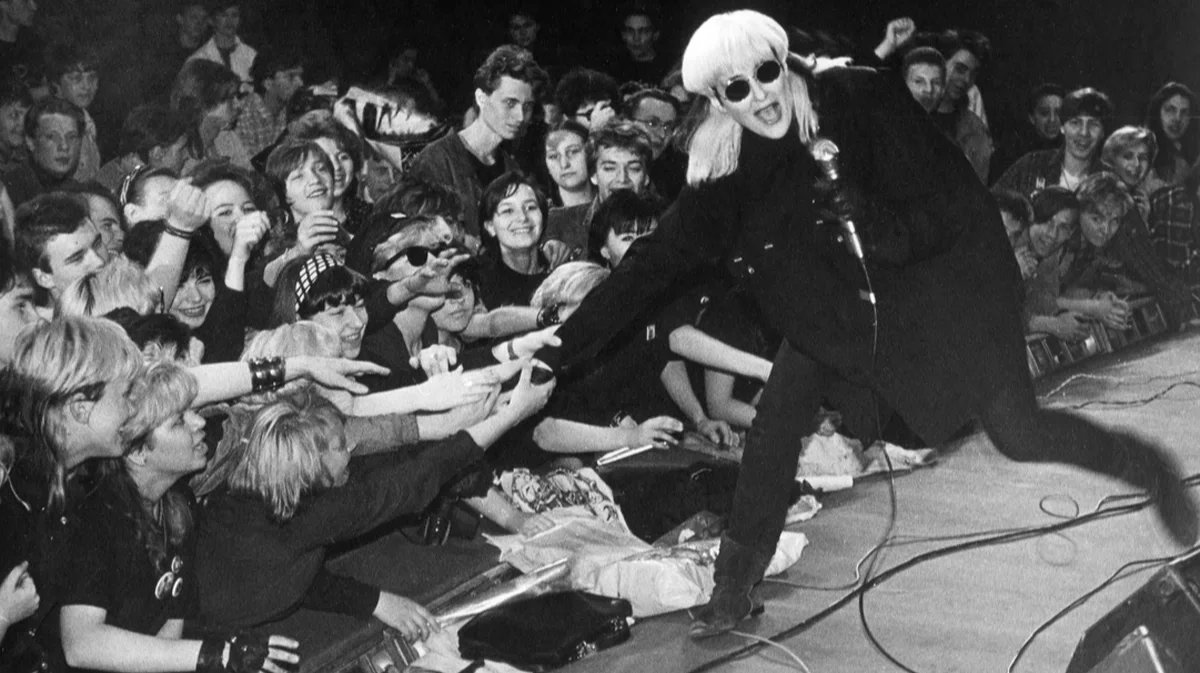

Joanna Stingray. Photo: Valery Vasilevsky

Following the end of communism, Stingray lived in Moscow for several years, where she wrote music with the likes of Tsoi and Grebenshchikov, fronted music programmes on TV, acted in films and performed at rock concerts with her musician friends, many of whom were by this time selling out stadiums. However, in 1996, having divorced Kasparyan and married Alexander Vasilyev from the group Tsentr, Stingray packed up and went back to the US when she became pregnant with her daughter.

However, years later, she began to go through her own photo and video archive and began writing books about the Russian rock music of the period, something she arguably knows more about than many of the musicians involved themselves. Iryna Khalip caught up with Stingray in Budva, Montenegro, for a conversation that careened unpredictably between English and Russian.

NGE: Have you ever wondered how the life of Joanna Fields might have turned out if she had never come to the Soviet Union and never become Joanna Stingray?

JS: I think it would have been a very boring life. When I was younger, I wanted to be a child psychologist. And then when I was a teenager, I worked in a clothing store. It was so boring, these 8 hours. Then my goal was to never work a 9-to-5 job. Then I decided to become a rock musician. And when I got to Russia, that was it. It was my destiny.

Stingray and Kasparyan’s wedding in Leningrad, 1987. Photo: Joanna Stingray

NGE: And why did you only start writing books over 20 years after you left Russia? I’ve always thought one needed to get them down on paper as soon as possible, while the memories were vivid and fresh.

JS: I wanted my daughter Madison to help me. She’s a really good writer, but she wasn’t very interested in the topic. We travelled all the time. I didn’t want Madison to only know Los Angeles. In 2018, we were on a two-week trip to Scandinavia, and we stopped in St. Petersburg for three days. Those three days changed everything for Madison. I introduced her to my rock star friends: Yury Kasparyan, Vitya Sologub, Seva Gakkel [of Akvarium], Boris Grebenshchikov. Boris and his wife Irina came to our hotel for dinner, and the next day we had to leave. Madison was very upset that she wouldn’t see Boris again. But on the morning of our departure, we spoke by phone and he said: “I’m on Nevsky [Prospekt, St. Petersburg’s main avenue]. Come.” And we walked along Nevsky. After that, Madison offered to help me, and my first book, Stingray in Wonderland, was published in 2019.

Kino with Joanna Stingray, Sergey Kuryokhin (Akvarium), critic Artemy Troitsky and Billy Bragg in Leningrad, 1986. Photo: Joanna Stingray

NGE: You compare yourself to Alice in Wonderland. Other Western tourists went to the Soviet Union, but none of them managed, having fallen down the rabbit hole, to come out the other side in Boris Grebenshchikov’s kitchen.

JS: I told you. It was fate. Before the trip, I called a school friend, and it turned out her sister was married to a Russian immigrant, Andrey Falaleyev. Falaleyev was from Leningrad and he told me to meet Grebenshchikov. He said he was a star of the Russian underground and gave me his number. I remember being surprised at the time. There’s rock in the Soviet Union? But for the next 12 years of my life, Russian rock and Russia itself were in my blood and the air that I breathed.

NGE: So why did you pack up one day and leave?

JS: I was pregnant. It was 1996, and I wanted to give birth in Los Angeles and come back. But when Madison was born, motherhood became my whole life. I didn’t want to devote less time to my daughter, and in Russia I would have had to. And there was no internet then. There were no cell phones, messengers. If you left, the door closed behind you. I stopped following Russian music and didn’t know what was happening there. I was living a different life. And then, in 2016, I thought: I have so many photos from that time, the whole life of that set of rock musicians is in these photos. We need to digitise them and make a website. Which I did, but didn’t expect such a reaction. It turned out a huge number of people remembered that time and those musicians and bands and wanted to know more. So Russia came back to me.

“Your face changes completely when you’re writing a book about Russian music, or watching an old video with Kuryokhin, or listening to Tsoi.”

Out of interest I decided to look on Facebook to see if any of my friends were there. I looked and there was Boris. Alex Kahn [a music critic and columnist for the BBC who translated all Stingray’s books into Russian] was on Facebook too. Boris came to Los Angeles in 2017, I met Alex in London in 2018, and then I went to Russia.

And when I saw Vitya Sologub and Seva Gakkel, it didn’t feel like we hadn’t seen each other for over 20 years. It felt like we’d seen each other the day before, that I’d returned to my family.

NGE: But we’re talking in Budva, Montenegro. You’re going to Belgrade the day after tomorrow. These are now centres of a new wave of Russian emigration, people who are against the war. Does your coming here mean that you support their position?

JS: I’ve always been against war. I was part of Kino’s Save the World concert back in 1986. The words “Save the World” are very important to me. I’ve always taken an anti-war stance.

Cover of Stingray in Wonderland

But Russia is part of my soul. My third husband, who’s American, has said to me: “Your face changes completely when you’re writing a book about Russian music, or watching an old video with Kuryokhin, or listening to Tsoi.”

He’s right. I have three jobs that help me pay for my house, car, and so on. Life has to be more than just making money and for me it’s Russian rock, but it’s this connection to Russians in general. And meeting people who love the same music as me and the musicians who changed my life is very important to me. I can’t go to Russia now, but I’ve discovered there are other countries where there are a lot of Russians!

I can always go back to Los Angeles to my three mundane jobs, but meeting the Russian audience gives me a feeling that I’m alive. When I made the Red Wave album, I just wanted Americans to hear Russian rock and understand that there were cool musicians in the Soviet Union. Now I feel it’s my destiny to preserve and spread the legacy of my friends, especially the ones that died.

People have often said: “You did so much for them, you brought them instruments.” I answer: “Do you know how much they did for me? They gave me something that money can’t buy.”

Stingray performs in Moscow, 1991. Photo: Joanna Stingray

NGE: When you were bringing in all these instruments and things, did you know what you risked going to prison for smuggling?

JS: When you’re passionate, you’re fearless. It’s only later, when you have your own children, that you realise how dangerous that was. I wasn’t afraid of anything back then. But I know now that if my daughter said something like ‘Mom, I heard there’s underground rock in North Korea, and I want to go,’ I would say: ‘No way. Are you crazy?’ I talked very, very quickly at the border and told customs officers that I was a singer, going on tour in the Soviet Union, and then to Paris, and that these were my instruments.

When I was taking the guitar — a red Fender Stratocaster — to Boris, the customs officers wrote down all the data on the back of my customs declaration, including the serial number, and warned me that they would check it again on departure. If the guitar came in, it should leave too. I didn’t know how to get out of that, but Boris reassured me. And do you know what we did? His friends Timur Novikov and Sergey Bugaev, aka Afrika, made a wooden copy. They even drew on the serial number. And painted the wood red. Customs didn’t raise an eyebrow.

Joanna Stingray, 1990s. Photo: Joanna Stingray

NGE: Joanna, I’ve wanted to ask you for 30 years. Why Kasparyan? You were at the centre of the rock elite, surrounded by the most talented musicians in the Soviet Union. Why did you go for Yury Kasparyan?

JS: I was a tomboy. I understood it was better to be one of the boys than with one of the boys. I loved spending evenings with Boris, Sergey Kuryokhin, Seva Gakkel, Viktor Tsoi. Of course they were flirting — like, Kuryokhin flirted with me — but because I was one of the boys, it never was serious. But I blame getting married to Yury on the Disney films that I grew up with in America. The princess meets a prince there, and her heart beats faster. So when I first saw Kasparyan — with the same dyed white bangs as me — my heart beat faster and I decided that he was my prince. We were together for three years and then divorced, but he is still my family. It’s more than love. It’s kinship.

The sixties was the heyday for American rock music. There was an explosion. That same explosion occurred in Russia in the eighties.

By the way, Grebenshchikov and I laughed about that later. I said to him: “Look, I know everything now. When Tsoi broke up with Mariana, Mariana had sex with Kasparyan. When you and Lyudmila broke up, Lyudmila had sex with Kasparyan. So why didn’t we have sex?!”

NGE: The lead singer of the group Televizor, Mikhail Borzykin, told me that Russian rock ended when it became part of show business.

JS: Back in the 80s, when I talked to Boris Grebenshchikov and Viktor Tsoi, they said that Western music was already boring, because musicians were signing contracts for millions, and were buying large houses, getting expensive cars. The protest and energy had gone out of the music. After all, when you have a million-dollar contract, you self-censor. You want to keep your boss happy to continue to get these millions.

But rock stars who don’t have a lot of money write music because they can’t not. It’s their life. They wake up and create rock. Real rock music doesn’t come from the mind. It comes from the heart. The sixties was the heyday for American rock music. There was an explosion. That same explosion occurred in Russia in the eighties. There’ll be other explosions, but no one knows when or where. Rock is something that no one can control or predict.

Georgy Guryanov, Ricochet, Yevgeny (Ai-Yai-Yai) Fyodorov (Tequilajazzz), Stingray and Viktor Tsoi. Photo: Joanna Stingray

NGE: What did Russian rock have that Western rock didn’t?

JS: I was too young, but for people who lived through 60s music, my whole life, when they were reminiscing or talking about it, they had this gleam in their eye and I kept thinking, ‘What was it? Why are these people, decades later, talking about it like it changed their life?’ When I met the Leningrad rockers, I felt it exactly. My friends didn’t have money, tours, TV broadcasts, but they carried on making rock music. It was the most honest form of music.

NGE: But the eighties came to an end, and with it the heyday of Russian rock. And nothing replaced the Leningrad rock elite. When you went to St. Petersburg in 2018, Grebenshchikov and your other friends were there. Some have now left, while others have been used in state propaganda. Does it hurt to think that your favourite city is now a wasteland?

JS: That’s happened to me before. This is the second time. So the first time was at the end of the 80s, where restrictions were lifted, all the bands could tour and so I would land in Leningrad and nobody was there, not even my husband was there because he was off touring with Kino. So that was the first time. But to be honest, it doesn’t matter where my friends are. Yesterday I met Misha Borzykin in Budva. We weren’t such close friends in Russia. I talked more to Kino, Akvarium, Strannye Igry, Alisa, but it felt like meeting family.

We’re part of the Leningrad rock family. Whenever I came back, I knew I was home. If it’s true that we live many lives, then I already lived in St. Petersburg 100 or 200 years ago. Of course it’s sad, but the rock scene didn’t become a wasteland overnight. When I went back to Los Angeles, Sasha Lipnitsky from Zvukov Mu or Seva Gakkel from Akvarium would call once or twice a year to tell me who else had died. It’s very sad. And yet, wherever we are, we’re part of the Leningrad rock club.

NGE: Your sister, Judy, married Vasily Shumov, the lead singer of Tsentr. Did you infect her with your love of Russian rock?

JS: It’s actually thanks to Judy that I ever went to Russia at all. She was studying in London, and I wanted to visit her. But Judy was just going on a university trip to the Soviet Union and there was a free place in her group, so I went to Russia too. And then Judy got really close to Akvarium. She was a hippy at the time, and Akvarium were very close to her philosophically. She and I went to Russia together more than once.

Joanna’s mother, Joanna, Yury Kasparyan and Viktor Tsoi sit around a kitchen table in Leningrad, 1987. Photo: Joanna Stingray

NGE: You were recognised on the streets, you were very famous in Russia. And then you went back to America and were just Joanna from California again. Didn’t you mind leaving at the height of your own popularity?

JS: I consider myself a very lucky person. I wanted to be a rock singer, I wanted to be famous, and it all happened. There were a lot of good things about fame, but a lot of bad things too. Many years later in Los Angeles, I am an ordinary 64-year-old woman with three jobs. But then I put on my sunglasses, and I’m the same Joanna who tells readers about the Leningrad rock scene, and after that meets the readers to sign books. And when the people around me in Los Angeles see my videos or photos of me in those glasses, they say: ‘We never thought you were like that.’ Being famous 20, 30 years ago was much easier. There were no internet haters back then. I really love Los Angeles because I’m just a regular person there.

Joanna Stingray signs an autograph, 1990s. Photo: Joanna Stingray

NGE: Have you finished your series of books on Russian rock now?

JS: I recently finished my last photo album, which goes from 1992 to 1996, before coming here. I thought that was it, but the publishing house has asked me to write about going back to Russia in 2018. I agreed. It’ll be about meeting Boris and Alex Kahn in London, Borzykin. There’s plenty of material. A few years ago, I was offered a contract for a joint American-Russian series, but then the American company said they wouldn’t film anything about Russia now.

But I did make a film about Mike Naumenko (Zoopark), and [Russian state broadcaster] Channel One was ready to buy it, but insisted I remove [war critic] Boris Grebenshchikov. It breaks my heart that they are trying to erase Grebenshchikov’s name from history. However, the publishing house AST published a book of his poetry after he was recognised as a foreign agent: it’s odd that no one stopped them, but they can’t sell it.

Joanna Stingray with Akvarium lead singer Boris Grebenshchikov. Photo: Joanna Stingray

I got my first impression of the Soviet Union from my father, Sidney Fields’ films. He directed a documentary, The Truth About Communism, that came out in 1962. The voiceover was done by Ronald Reagan. The film featured a Soviet newsreel with [Stalin’s rival for power Leon] Trotsky blotted out. So I saw in early childhood how names were erased in Russia. And now it hurts a lot to see them try to erase Boris’s name.

NGE: Your father warned you not to travel behind the Iron Curtain, they’re trying to erase the name of your close friend Boris Grebenshchikov from Russian music history, and yet you still miss Russia?

JS: Yes, especially St. Petersburg. There’s something I could never understand about my Russian friends and Russian people, the connection to Mother Earth. As for Americans, almost everybody that I know gets cremated but I even have in my will that when I die, some of my ashes have to go to Russia and when I told Yury, he said that’s a great idea. “They can sprinkle some on Tsoi and some on Kuryokhin and you’ll be with your friends again.” How can I not love that?