When the full-scale invasion of Ukraine began, Montenegro announced that its foreign policy would align with that of Western countries, and resolved to impose sanctions on Russia. But lax enforcement has turned the country into a safe-haven for Kremlin-connected elites right on the European Union’s periphery.

The resort town of Budva is picture-perfect: surrounded on one side by the turquoise Adriatic Sea and mountains on the other. Its popularity among tourists has spurred development that residents worry has tarnished the landscape and invited corruption.

Oleg Deripaska. Photo: Roscongress

In the marina near Budva’s old town, pleasure boats for tourists bob next to private yachts flying flags of St. Vincent and the Grenadines. A local Ukrainian businessman said he’d seen Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska at the marina on his yacht. It’s no secret that the oligarch owns a luxurious estate nearby, where he reportedly hosted Telegram co-founder and CEO Pavel Durov shortly before his arrest last year.

Deripaska, the founder of Russian aluminium giant Rusal and its parent company En+ Group and Basic Element — one of Russia’s largest industrial conglomerates — has been under EU and US sanctions for two years, and in 2024 Montenegro imposed additional sanctions on the metals tycoon.

Yet in January, officials in Montenegro greenlit a project linked to Deripaska to construct a five-star hotel near Trsteno Beach, not far from Budva. The land is owned by an offshore company that local reporting revealed is backed by Deripaska. The company has owned that land for 20 years.

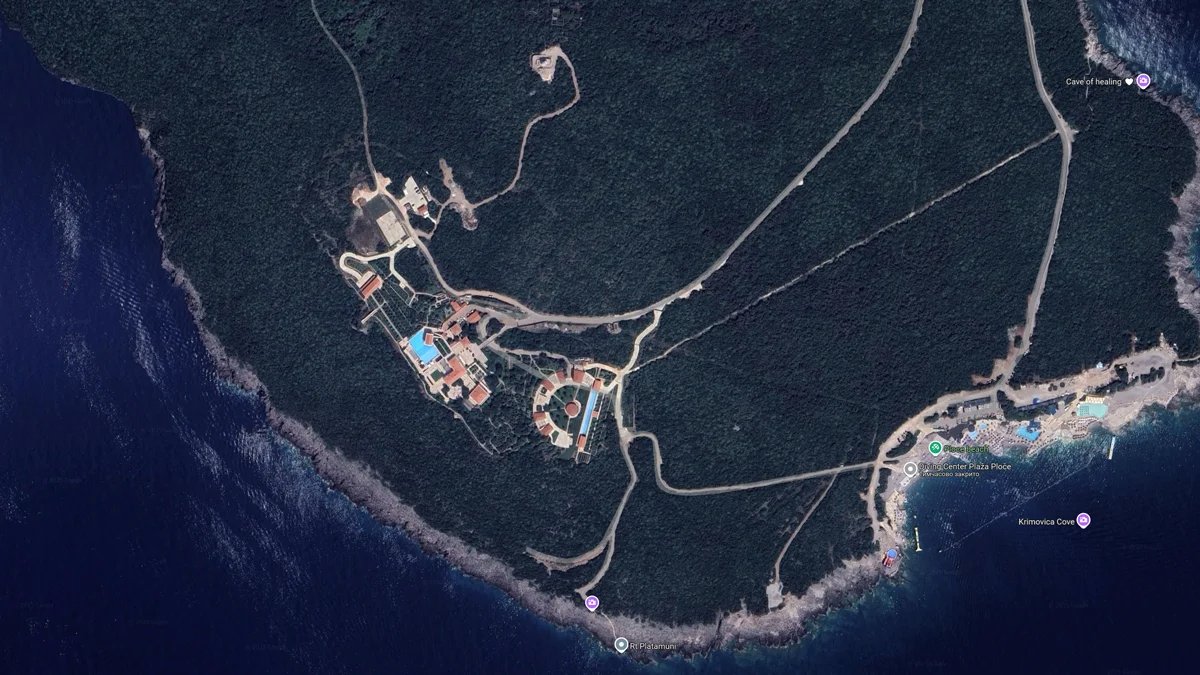

Cape Platamuni is home to Deripaska’s luxury private estate. Satellite images show several swimming pools and more than a dozen buildings. The complex is more like a micro-village.

Cape Platamuni, with Villa OVD in the centre. Photo: screenshot, Google Maps

In 2005, Overseas Assets Management acquired a plot of land at Cape Platamuni. At the time, the identity of the owner was hidden behind another offshore company from the British Virgin Islands, but local media quickly linked that company to Deripaska. In 2017, during legal proceedings in the US, authorities also named Deripaska as the company’s owner. In January 2024, Montenegrin firm Overseas Assets, and the villa that it owns, passed into the possession of another company.

Since the mid-2000s, Deripaska has invested billions of euros in Montenegro’s economy.

Since the mid-2000s, Deripaska has invested billions of euros in Montenegro’s economy. But his relationship with the local authorities changes dramatically depending on the country’s foreign policy.

Montenegro has been a candidate for EU membership since 2010, and joined NATO in 2017. But even as it outwardly pursues European integration, Montenegro shows that its ties to Russia remain strong.

In the mid-2000s, Deripaska’s money was only too welcome in Montenegro. In 2005, his holding company En+ Group acquired the Podgorica Aluminium Plant, KAP, the largest industrial enterprise in the country. The plant was known as the “pillar of the economy”. Before the 2008 global financial crisis, about 10% of Montenegro’s population was directly or indirectly dependent on it. According to some estimates, at its peak, the company generated up to half of the country’s GDP.

Deripaska had also acquired the controlling stake of the bauxite mine in Nikšić — the sole source of raw materials for the plant. At the time, Montenegrin authorities saw Russian investment as life-saving for floundering state-owned enterprises.

The KAP plant in Podgorica, 9 September 2013. Photo: Stevo Vasiljevic / Reuters / Scanpix / LETA

Big business went hand in hand with political influence. Deripaska’s influence grew so great that the opposition Movement for Change called him the “financial right-hand man” of Prime Minister Milo Đukanović.

In 2019, the extent of Deripaska’s political involvement started becoming clear. In 2005, Deripaska discussed the Montenegrin independence referendum with Foreign Minister Milan Roćen. Roćen asked him to use his influence over Canadian billionaire Peter Munch to lobby the US for favourable referendum conditions, following unwelcome pressure from Europe.

“I suspect Roćen still provides a link to both Deripaska and the Russian authorities.”

Prior to becoming Foreign Minister, Roćen was the ambassador to Russia from 1998 to 2003. He has acted as a key interlocutor during sensitive talks between the two countries ever since. “I suspect Roćen still provides a link to both Deripaska and the Russian authorities,” said the US-based Montenegrin political scientist and journalist Ljubomir Filipović.

But the 2008 global financial crisis radically altered Deripaska’s position in the country.

A view of KAP, Podgorica, 9 September 2013. Photo: Stevo Vasiljevic / Reuters / Scanpix / LETA

The financial crisis hit the aluminium business hard: metal prices collapsed, and by 2009 KAP was on the verge of bankruptcy. The Montenegrin government bought shares from Deripaska, increasing the state’s stake to 29%, and provided guarantees for loans to the tune of €131.7 million.

In 2013, Montenegro launched bankruptcy proceedings and Deripaska lost control of the plant without receiving compensation. In October 2013, KAP was officially declared bankrupt with debts of about €350 million. The aluminium smelter and bauxite mine’s assets were sold off and Deripaska lost his business.

Đukanović, who led Montenegro under different titles for most of three decades between 1991 to 2020, essentially threw Deripaska under the bus when his survival depended on it.

“As a political leader, Đukanović was like a chameleon,” said Filip Kovačević, a professor of politics at the University of San Francisco. “When he realised that it would be more politically profitable to criticise Putin and Deripaska, he started doing so.”

In the 2000s, Đukanović became the pro-European architect of Montenegro’s independence from Serbia. While remaining officially pro-Western, he also established ties with Moscow and attracted investment from Russia. That all changed after the 2008 global financial crisis. In 2017, against the Kremlin’s protestations, Montenegro finally cemented the break from Russia by joining NATO and pursuing negotiations on EU membership.

Even though he had lost his main business interests in Montenegro, Deripaska didn’t stop attempting to wield influence in the country. After 2013 he chose to ally himself with the opposition instead. According to US intelligence, Deripaska financed the pro-Russian Democratic Front (DF) bloc in Montenegro’s 2016 parliamentary elections. The DF — a coalition of Montenegrin parties focused on an alliance with Serbia and Russia — has for years fiercely opposed Đukanović.

Montenegrin President Milo Đukanović, 2021. Photo: Virginia Mayo / EPA

The confrontation between Russia and the West soon escalated. Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, which led to the first round of international sanctions, and Deripaska began having his own problems in the West.

First Spanish authorities suspected him of money laundering through real estate deals. Then his name surfaced in an investigation into organised crime. Spain handed the material to Russian law enforcement, which quietly terminated the “Spanish case” in 2017 for lack of evidence.

But Deripaska came under fire again in 2018 when he was sanctioned by the US, which called his businesses Kremlin proxies and again he was accused of money laundering. In 2021, the FBI raided homes connected to Deripaska while investigating alleged sanctions violations. Deripaska denied all the accusations.

In 2022, after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Deripaska was sanctioned by the EU and the UK and stripped of his Cypriot citizenship. He went from desirable investor to persona non grata in the West.

Deripaska’s estate and other business projects in Montenegro have not been frozen.

The yacht Clio in Göcek Bay in southwestern Türkiye, 16 April 2022. Photo: Yörük Işık / Reuters / Scanpix / LETA

Deripaska was formally sanctioned by Montenegro in 2024. His yacht, the Clio — since renamed Altair — which regularly came to the Adriatic Sea, has been cruising between Sochi and Türkiye for the past two years. But Deripaska’s estate and other business projects in Montenegro have not been frozen.

Local media reported that Telegram creator Pavel Durov stayed at his villa on Cape Platamuni in the summer of 2024. It is unclear whether Deripaska himself was present at the time.

His companies in Montenegro own another 480,000m² of land on the coast between Budva and Kotor, adjacent to his estate, which he purchased in 2004 from the local municipality. The deal itself caused public outcry and led to protracted legal proceedings. Politicians demanded the sale be annulled, but the land remained in his hands.

Deripaska reportedly first applied for planning permission for a large tourism complex in 2016, but was turned down. In 2024, permission to build the complex was granted. The site near Trsteno Beach will host a five-star hotel, apartments and other infrastructure. The permit was signed off by a pro-Russian DF minister, Slaven Radunović.

Deripaska has denied being involved in the project, but declined to answer Novaya Europe’s detailed questions. The Montenegrin government also chose not to answer our questions regarding who was behind the project and why, despite sanctions against Deripaska, companies tied to him were planning new investment in the country.

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]

VPNovaya

Help Russians and Belarusians Access the Truth