Russian prisoners of war who were repatriated as part of the largest prisoner exchange of the war so far — a “1,000-for-1,000” swap with Ukraine in late May — are reportedly being sent back to their combat units, activists from Get Lost, an organisation that helps Russian men either to avoid conscription or to desert, have told Novaya Gazeta Europe.

Get Lost has raised concerns that the repatriated soldiers could soon be redeployed to the front line in Ukraine, in direct violation of the Geneva Conventions, which mandate that captured servicemen cannot be compelled to return to active military service upon their repatriation — especially not a conflict from which they have recently been released.

There have been repeated instances in which the relatives of freed Russian POWs have been barred from seeing their loved ones following prisoner exchanges. The men — including those who were wounded in action — are often sent straight back to the front line. Human rights organisations warn that the same could happen to the wounded or very young soldiers exchanged in the most recent prisoner swap, which began on Monday after being agreed at face-to-face negotiations between the two sides in Istanbul on 2 June.

Family members of soldiers involved in the prisoner exchange on 19 March say they, too, were denied the chance to reunite with their loved ones after their release from captivity, as the soldiers were quickly returned to active combat and deployed to the front.

According to one woman whose relative was among the exchanged soldiers, the men were initially held at a military base outside Moscow before they were put on a military truck and transported to Donetsk, in Russian-occupied eastern Ukraine.

One of the men later managed to contact his family and said they had reached Makiivka, another Russian-occupied city in the Donetsk region. The following day, another soldier called his relatives to say that they had been taken to an unknown location and that all their personal belongings had been confiscated. Shortly afterwards, the men, who were being kept under constant guard, told their families that they were being sent back to the front.

“Our boys went through hell in captivity … Most of them have shrapnel wounds, concussions and broken bones that healed without proper medical treatment. One lost a leg. They all need medical care, an evaluation by a military medical board, and ultimately, time to recover on leave. But instead, they’re being sent to the front while still unwell,” the relatives said in a statement published on Telegram.

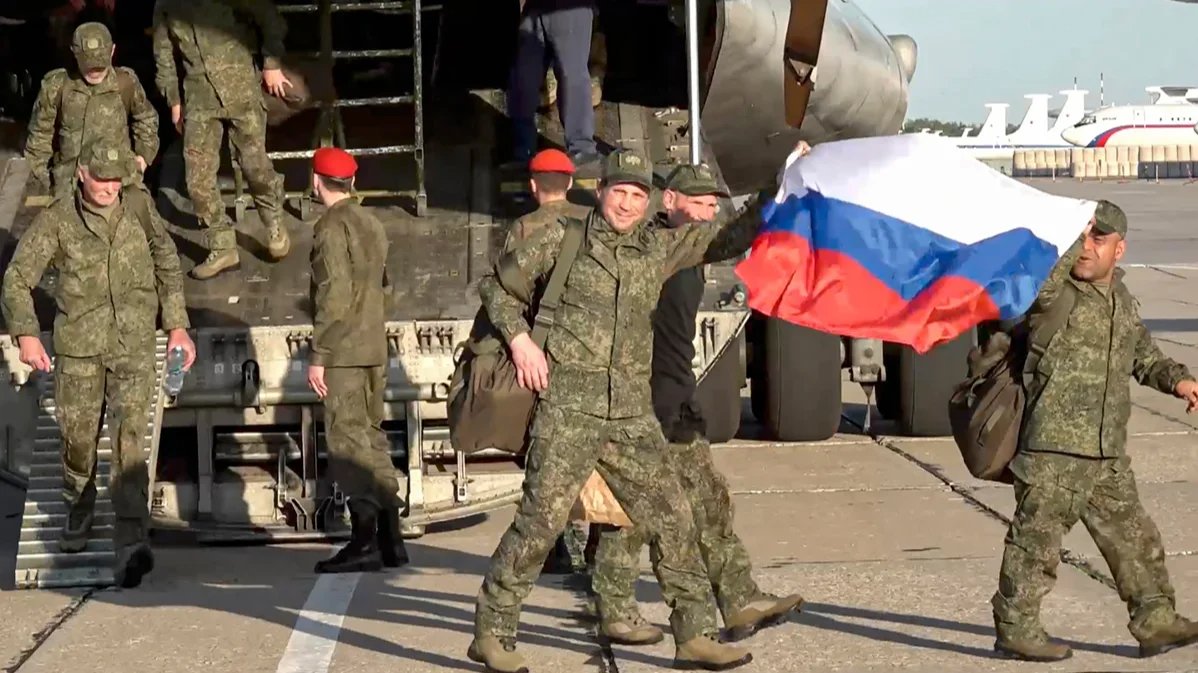

Prisoners of war returned to Russia in an exchange at Chkalovsky Air Base, Moscow region, 24 May 2025. Photo: Russian Defence Ministry / EPA / Scanpix / LETA

Get Lost has received numerous appeals from soldiers and their families about similar cases over the past several months, the organisation’s spokesperson Ivan Chuvilyaev told Novaya Gazeta Europe.

Once a prisoner exchange is complete, the first thing that Russian soldiers face is an interrogation by the Federal Security Service, Chuvilyaev says, after which they are sent to their military unit. While in theory this could be seen as a formality, upon arrival many soldiers are simply forced to sign a new contract with the Russian Defence Ministry, he explains.

Under Russian law, former prisoners of war and hostages retain their status as active-duty servicemen.

Furthermore, in some cases, the military units are located on occupied territory in Ukraine, which means the soldiers simply have nowhere to go. “Refusing to sign is not an option and, in many cases, the paperwork is signed on their behalf without their consent,” Chuvilyaev continues.

Article 117 of the Geneva Conventions explicitly prohibits the use of former POWs to perform active military service. However, both Russian and Ukrainian legislation prevents soldiers from voluntarily resigning from the armed forces during wartime, including those who have been captured. In practice, all contracts with Russia’s Defence Ministry are considered open-ended and indefinite.

Under Russian law, former prisoners of war and hostages retain their status as active-duty servicemen. In other words, time spent in captivity is not considered grounds for discharge from the military, explains a lawyer from the Russian human rights initiative Peace Plea, who for security reasons spoke to Novaya Gazeta Europe on condition of anonymity.

“If a soldier’s health has deteriorated after captivity, in theory he has the right to request an examination by a military medical board. And if that board confirms his health has declined, he could then seek a discharge on medical grounds. But in practice, achieving that is extremely difficult right now,” he added.

While the Geneva Conventions prohibit the deployment of former prisoners of war who were released as part of an armistice, they do not specifically mandate how prisoners released before the the end of hostilities should be treated.

As lawyer Maxim Grebenyuk points out, the Russian Defence Ministry appears to be invoking Article 110 of the Geneva Conventions, which states that only soldiers who are “incurably wounded and sick”, as well as soldiers who are unlikely to recover within a year and soldiers whose mental and physical fitness has been “gravely diminished”, are to be repatriated.

“Commanders may simply ‘fail to notice’ that a soldier is seriously ill.”

According to the ministry, soldiers who don’t fall into these categories cannot be discharged from the military. The ministry has also cited Vladimir Putin’s September 2022 decree ordering “partial mobilisation”, according to which being returned from captivity is insufficient grounds for earning a military discharge.

A second round of negotiations between Russia and Ukraine took place in Istanbul on 2 June, during which the two sides reportedly agreed on a new prisoner exchange involving all known seriously ill prisoners of war and those under the age of 25. However, Peace Plea warns that even these vulnerable groups could be sent straight back to the front line.

“’It’s essential that returning soldiers proactively demand a military medical evaluation,” the organisation says. “Commanders may simply ‘fail to notice’ that a soldier is seriously ill. Complaints must be submitted wherever possible — to the unit’s command, the regional medical authority, the military Prosecutor’s Office, and the Defence Ministry. Soldiers should also file an official report demanding they be referred to a military medical board.”

Despite international legal protection, this is not the first time Russia’s Defence Ministry has sent former POWs back to the front, as the cases of Vasily Grigoryev and Dmitry Davydov in 2024 attest.

According to the organisation Military Lawyers, both men had spent six months in Ukrainian captivity before being returned to Russia as part of a prisoner exchange and were redeployed to the front line within a month.

The two soldiers eventually fled their field camp and hitchhiked to Moscow, where they sought legal assistance. While legal proceedings were underway, they were temporarily assigned to a military unit near Moscow, where Davydov died of “sudden cardiac arrest” just three days after filing a complaint with the military Prosecutor’s Office.

Additionally, Chuvilyaev told Novaya Gazeta Europe that soldiers captured in Russia’s southwestern Kursk region, a part of which was occupied by Ukraine for several months in late 2024 and early 2025 , were also sent back to the front line after being exchanged last September.

“In the Kursk region, most of those captured were conscripts. After the exchange, these conscripts were sent to the units to which they had been assigned. However, both they and their families naturally expected that after captivity they would be returned home,” he said.

There have also been reports, most notably from independent outlet Holod, that former prisoners of war who were recruited from Russian penal colonies were being used to carry out labour on the front lines. According to these reports, around 30 former convicts repatriated to Russia in the summer of 2023 were sent to the occupied town of Novoazovsk, in the Donetsk region, to dig trenches at military training grounds.

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]

VPNovaya

Help Russians and Belarusians Access the Truth