As a rapid succession of grey Soviet apartment blocks, snow-covered industrial ruins and bleak war memorials flickers across an iPhone screen accompanied by Belarusian post-punk band Molchat Doma, whose melancholic Cold Wave style places it at the gloomier end of the synth-pop spectrum, it’s hard to miss that Soviet and post-Soviet aesthetics have been experiencing a surprising renaissance on TikTok and Instagram.

Jonas Heins

MA in European and Global Studies at University of Padova, Italy

A fully-fledged social media trend reaching millions, these evocative videos are pitched at teenagers and young adults likely to identify with the aesthetics of life behind the Iron Curtain, though instead of mythologising the Soviet Union as a utopia of peace and international brotherhood, it focuses instead on the harshness and poverty of the post-Soviet years, and, in particular, on the bleakness and depression of what Svetlana Alexievich called “second-hand time”.

It’s a narrative crafted for the children of the 1990s and early 2000s, whose biographies often begin in the former Soviet Union before continuing in the West. Yet amid the understandable desire to recapture the happiness of childhood, a troubling romanticisation often creeps into this aesthetic and what at first appears to be a generation’s harmless re-engagement with its own cultural roots in many cases also carries problematic undercurrents. Alongside nostalgia, these videos often romanticise both hardship and traditional gender roles and provide a blank canvas onto which political manipulation can be projected.

“When these teenagers engage with such nostalgic content on social media, these warm feelings towards a harsh past get amplified and directly contradict the official historical narrative they learn in school,” says Dmitri Teperik, the former director of Estonia’s International Centre for Defence and Security, a think-tank. “In diverse societies these different mental anchors can contribute to divergent understandings of the past, potentially leading to a clash of memories eroding social cohesion.”

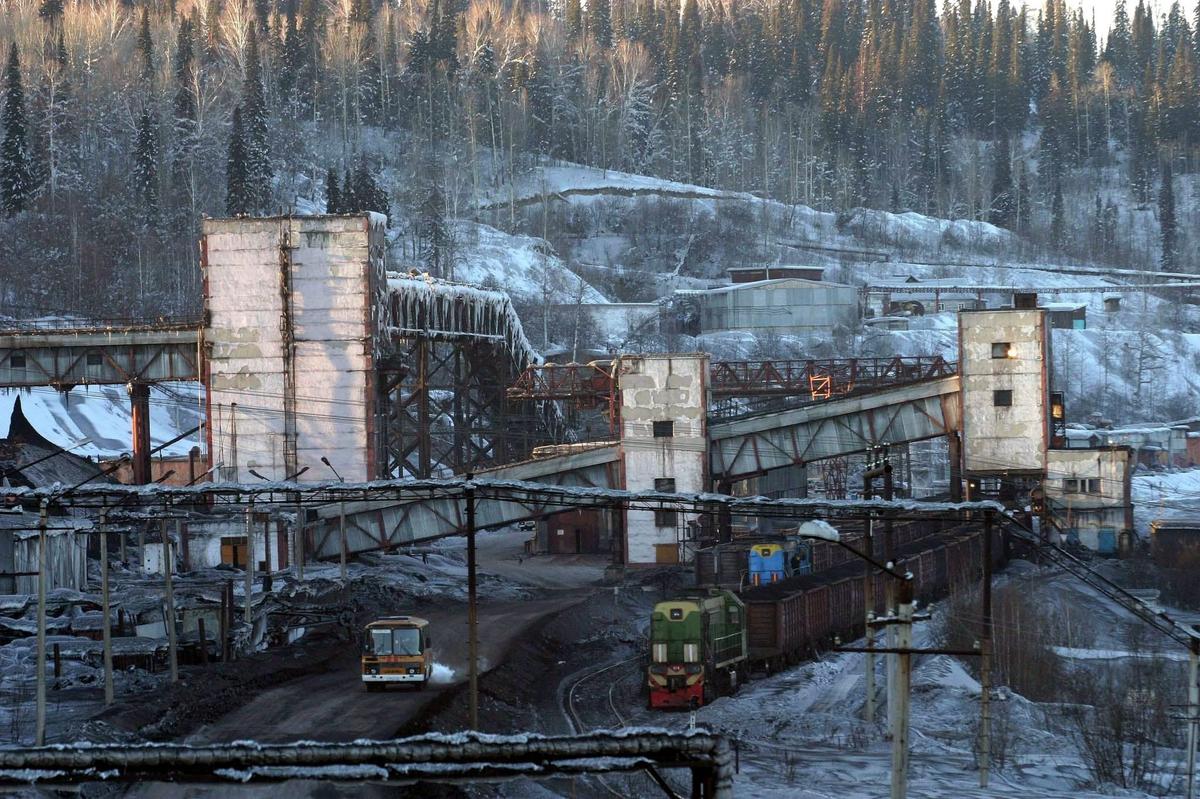

The city of Nefteyugansk in the Urals, home to the second largest oil production complex in Russia. Photo: EPA / YURI KOCHETKOV

In an increasingly uncertain world, people understandably seek comfort in the familiar, Teperik says, typically their own idealised memories from childhood, when “even if things weren’t objectively better, the perceived normalcy is comforting.” However, when nostalgia for the past morphs into a desire to recreate it, “that’s when tensions can arise”, he adds.

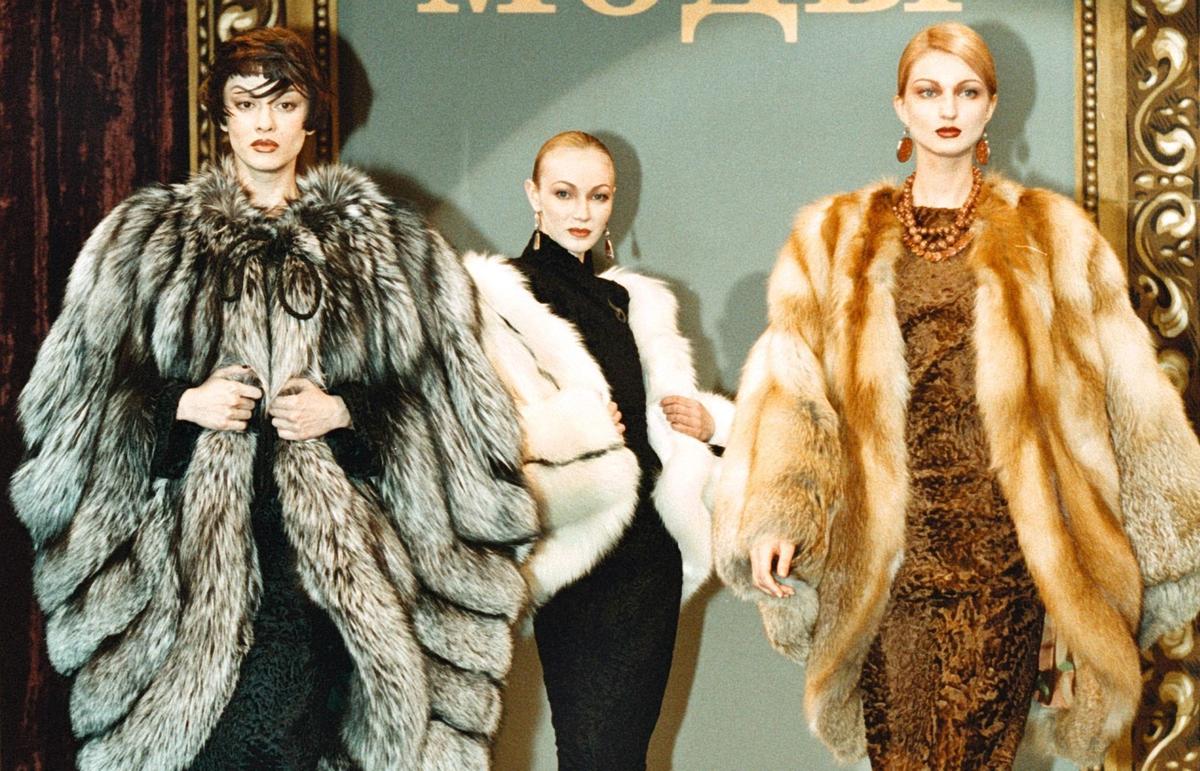

Another trend seeks to capitalise on contextless aesthetics by exploiting stereotypes and clichés. In videos tagged SlavicTrend or simply Slavic, young people present themselves as a supercharged version of what they believe typically Slavic to be: women cloak themselves in furs with full makeup and elaborate jewellery, while young men channel the gopnik — or thug — aesthetic, mimicking the gangsters of the post-Soviet era by wearing fake Adidas tracksuits, doing the so-called Slavic squat and getting blind drunk on vodka. In the background of these videos one can hear either eighties Euro synth-pop like Modern Talking or early 2000s Russian pop songs such as the perennially popular Katya Lel song Moy Marmeladny.

For many young people with Eastern European roots who have grown up in Western societies, this ironic reappropriation of stereotypes is an attempt to redress the sense of otherness many of them experienced in childhood, and, in many cases, their desire to resist the roles assigned to them is understandable.

As historian Larry Wolff wrote as far back as 1994, the “civilised West” has defined itself for centuries in contrast to the supposedly “backward East”, whether in the brutal 19th-century partition of Poland, the genocidal policies of warfare and starvation carried out during the 20th century, or the exploitation of Eastern European labour in the 21st. Young social media users are reclaiming the very clichés that once made them targets of ridicule, reframing Ladas, Stolichnaya, and Soviet retro aesthetics as symbols of an identity that no longer seeks validation from the “civilised West” but proudly asserts its own self-worth.

The success of artists such as Liaze, a German rapper born in Russia whose 2023 hit 2003 addressing such themes gained over 11 million views on YouTube, is no coincidence. The catchy track, with lyrics in both German and Russian, distills the experience of growing up between two cultures and samples a tune from Soviet children’s show Crocodile Gena that is instantly recognisable to anyone who spent their childhood in the former USSR.

But while many engage with such wry reinterpretations as quiet acts of emancipation, others embrace the trend with no irony whatsoever, presenting themselves as archetypes of the post-Soviet aesthetic, in which men are still “real men” — tough, brutal when necessary, yet always gallant towards women — and sparing no thought about the very real violence and misery of the times while they channel 1990s gangsters.

The Yesaulskaya coal mine in Novokuznetsk, southern Siberia, 9 February, 2005. Photo: EPA / RASHID SALIKHOV

By contrast, female exponents of this aesthetic are slender, beautiful paradigms of traditional femininity who adore their children and obey their husbands, and who often contrast their own modest and traditional appearance with that of Western women, who are portrayed as overbearing, cheap, and lacking in self-respect.

Besides the ignorance of those cosplaying the 1990s, this self-positioning under the term Slavic occurs within a complicated historical context. Nostalgic idealisation and a romanticised notion of brotherhood have for centuries been used as traps. As the Czech writer and politician Karel Havlíček Borovský wrote in the 1850s, “Russian gentlemen first assure us that we are all Slavs so that they could later say that everything Slavic is Russian and must be subordinated to them”.

Indeed, the idea of a common Slavic identity is an old one that can be traced back to Pan-Slavism, a mid-19th century political movement that sought to unite all Slavic peoples, many of whom at the time were subjects of the multi-ethnic Habsburg Empire.

Models display fur coats made by St. Petersburg designer Klaudia Zavialova during Russian Fashion Week in Moscow, 17 November 1998. Photo: EPA / DMITRY ASTAKHOV

In today’s Russia, Pan-Slavism is undergoing a troubling revival, led by propagandists such as Alexander Dugin, whose “Russian world” philosophy seeks to bring all Slavic peoples under the cultural and political leadership of Russia. For Putin and his ideological allies, the separation of Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians into sovereign states is a temporary anomaly inconsistent with their historical unity, and given that, in Putin’s words, Russia’s borders “end nowhere”, all nations that were once part of the Soviet Union or even the Russian Empire, remain part of the Russian world, whether they like it or not.

The concept of a Russian world is of course one of the main arguments used to justify the invasion of Ukraine, and one of its principal exponents is the Russian Orthodox Church, which has tirelessly promoted the idea of Russia being the guardian of true Christianity, a bulwark against a decadent West corrupted by a multitude of sins from homosexuality to individualism.

Russia has already successfully monopolised Soviet identity, despite the Soviet Union having been a multinational state, according to Teperik, who notes that the label Slavic has become shorthand for Russian, and that the Russian regime benefits from this.

Of course it would be an exaggeration to call a short clip from Nu, Pogodi! — the Soviet equivalent of Tom and Jerry — a direct recruitment tool for Russian imperialism, as Teperik points out, but we need to pay attention when seemingly innocent content becomes part of a broader narrative, or fits into a coordinated effort to influence perceptions.

Indulging in nostalgia and idealising a past many were too young to have experienced themselves opens the backdoor to instrumentalisation by the Kremlin and other illiberal forces. Aesthetics and clichés void of any context or critical debate provide fertile soil for those seeking to exploit identity-based disruption. While cosplaying as a 1990s gangster on TikTok might seem harmless enough, Ukrainians are dying every day while the Kremlin seeks to bulldoze the accomplishments of free and democratic societies that have left their Soviet past behind them.

Looking to the past cannot be allowed to obscure the realities of the present. “While it’s important to respect the past, we shouldn’t overfocus on it, especially not to the point of allowing nostalgia to shape our future”, Teperik cautions. “For younger generations, being overly nostalgic or fixated on historical trauma is not the right path. They should be future-oriented, thinking critically and creatively about what comes next.”

Views expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the position of Novaya Gazeta Europe.