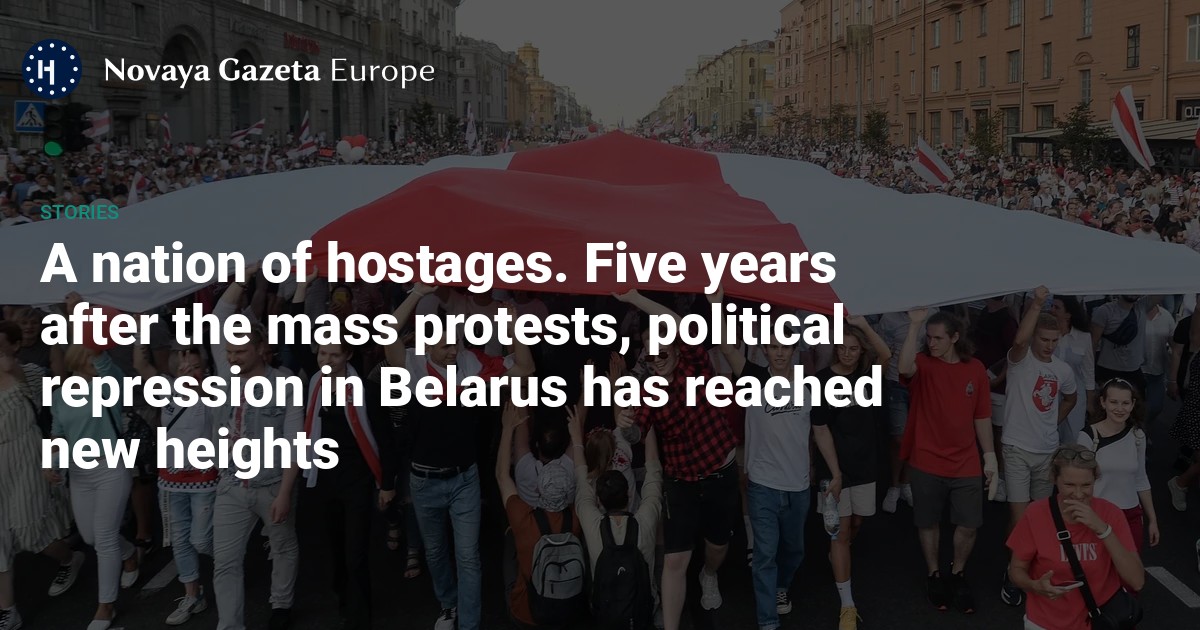

Belarus held presidential elections on 9 August 2020. The official result — another landslide for Alexander Lukashenko — was met with disbelief by much of the population. From the next day, hundreds of thousands took to the streets protesting against electoral fraud and police violence. For a brief moment, it seemed that the people had broken the course of history.

But the dictatorship stood firm — or rather, it was helped to stand firm. Hundreds of thousands fled the country. Thousands ended up behind bars. Dozens were killed. Lukashenko’s regime did not soften; instead, he built a system where repression became the foundation of his rule. Today, Belarus is a country held hostage — by a dictator, by Russia, and by fear.

Belarus in 2025 is a country where fear lives in every home; where a “like” or a comment online can land you in prison; where the “wrong” colour clothing or a pendant in the shape of your country can lead to a prison sentence; where people avoid greeting each other so as not to betray a “dangerous” acquaintance; where everyone has a relative or friend who has been arrested for political reasons; where even helping someone — or writing them a letter — can be dangerous.

It is also a country where the scale of politically motivated cases can only be compared to a war against its own people. According to Belarusian human rights centre Viasna, as of the end of July 2025, 8,519 people have faced criminal prosecution for political reasons since May 2020, 7,190 have been convicted, and 33 have been sent to compulsory psychiatric treatment.

As of early August 2025, 1,183 political prisoners are known to be behind bars — 175 of them women, the highest figure in modern Europe.

The numbers are likely higher — many cases go unreported. As of early August 2025, 1,183 political prisoners are known to be behind bars — 175 of them women, the highest figure in modern Europe. The number includes former presidential candidates, teachers, doctors, factory workers, and even Nobel Peace Prize laureate Ales Bialiatski.

Inside, prisoners face beatings, starvation, denial of medical care. They are forced to sew military uniforms or make weapons parts — some later used by Russian forces in Ukraine — for hours on end, for a wage of a few rubles a month, in what is essentially slave labour and a conveyor belt of torture organised by the regime.

Families outside suffer too: job loss, confiscated property, and the erosion of any belief that change is coming. At least eight political prisoners have died in custody; more than 50,000 people have been detained for political reasons in the last five years.

Police detain a protester demonstrating against electoral fraud in Minsk, Belarus, 10 August 2020 года. Photo: Yauhen Yerchak / EPA

The official enemy is “extremism” — a term so elastic it includes almost any dissent. Independent media outlets are banned, as are hundreds of books and films and thousands of websites and social media channels. Bands, bloggers, even a Belarusian jewellery brand have been labelled “extremist”.

A document listing “extremist materials” now runs to 1,800 pages and more than 7,000 items. Over 5,500 people are on the government’s “extremist” list, 1,326 on a “terrorist” list. Reposting a song, or a photo of a pendant, can mean prosecution.

The crackdown has gutted civic life. Around 600,000 people — around 6.57% of the population — are thought to have left the country since 2020, though official figures are suppressed. Independent journalists and activists now work mostly from exile; inside Belarus, the information space belongs entirely to state propaganda.

“We see the regime evolving towards totalitarianism,” notes political analyst Valery Karbalevich. “Political repression is spreading to new categories of the population suspected of disloyalty. Once the obvious opponents are gone, the regime will seek out the less obvious. By such actions, it makes clear to all opponents: no one will have a peaceful life.”

Activists remember a protester who died at a demonstration, Minsk, Belarus, 15 August 2020. Photo: EPA

The International Committee for the Investigation of Torture in Belarus — an NGO that documents testimonies from survivors — has collected statements from around 2,000 victims since 2020.

One described conditions that, they said, were “like a Nazi concentration camp”: “People were beaten at every stage. First they made us stand against the wall in painful positions. Then they added barbed wire so we had to bend lower; anyone who moved an arm or leg was hit with batons. Every day the abuse got worse. The torture factory worked day and night. Men lay in pools of blood and excrement, begging for help, and still they were beaten.”

In October 2024, the Belarusian Interior Ministry declared the committee an “extremist formation”, and named its founders, Viktorya Fiodorava and Siarhei Ustsinau, as “complicit” in it.

Not a single security officer or senior official who gave criminal orders in 2020 has been prosecuted. No one has been held accountable for the torture thousands have endured since.

Dictator Alexander Lukashenko addresses supporters, Minsk, Belarus, 16 August 2020. Photo: Yauhen Yerchak / EPA

Over the past five years, Lukashenko has perfected the art of trading people. He releases gravely ill prisoners or those nearing the end of their terms, calling it “mercy” — but in the same month, dozens of new prisoners of his dictatorship take their place.

“This cynical tactic has been honed over the years: to release a few prisoners in exchange for political favours,” Ustsinau explains. In 2015, Lukashenko freed six opposition figures to reopen talks with the EU, winning sanctions relief. In February 2022, a similar gesture bought quiet from European capitals, when Lukashenko released Swiss-Belarusian citizen Natalia Hersche, arrested during the 2020 protests.

Between 2023 and 2025, “hostage diplomacy” became an open part of Minsk’s foreign policy. In June this year, days before a visit from a US envoy, Lukashenko released Siarhei Tsikhanouski, one of his most prominent opponents.

“Right now, at this very moment, in Belarusian prisons and penal colonies, people are still being tortured.”

Ustsinau believes Lukashenko’s main goal is to have sanctions lifted and restore relations frozen by his role in the war in Ukraine.

“But Lukashenko is completely dependent on Moscow. Belarus has no room to manoeuvre. The country’s future is directly tied to how the war in Ukraine ends,” says Professor Gwendolyn Sasse of the Centre for East European and International Studies in Berlin.

“Even if it seems Lukashenko is releasing political prisoners in batches and the regime is ready to surrender — that is an illusion,” says Ustsinau. “Repression in Belarus has not stopped. Right now, at this very moment, in Belarusian prisons and penal colonies, people are still being tortured.”

Demonstrators protest the results of the presidential election, Minsk, Belarus, 13 August 2020. Photo: Tatyana Zenkovich / EPA

Lukashenko came close to losing power in 2020. Vladimir Putin saved him — with money, security guarantees, and political backing. The price was sovereignty. Five years later, Minsk’s dependence on Moscow is extreme.

“Lukashenko remains in the saddle — perhaps more firmly than ever — because he radicalised the system and leaned completely on Putin,” notes German journalist Ingo Petz.

Today, Belarus is more dependent on Russia than ever. Russian troops operate freely on its territory, which has hosted missile launches and troop movements against Ukraine. Nuclear weapons have been stationed close to the Polish border. Belarus has effectively become a front-line zone for Russia — its “north-western edge”.

In return, Belarus has been hit by Western sanctions targeting key sectors of its economy, including potash exports — a pillar of the regime’s finances. The EU has closed much of its land border; flights to Europe are suspended.

The hope for freedom survives, underground or in exile.

To counter this, Lukashenko tries to flirt with China or make signals to the US, but he can’t take a step without looking to Moscow.

The story of Belarus since 2020 has no neat ending. Change did not come then, and it is unlikely to come this year. But the events of that summer are etched into memory.

The hope for freedom survives, underground or in exile. Former prisoners speak out about torture; families campaign for the release of loved ones; activists document abuses.

The thousands in jail are not only victims but symbols — of defiance, and of a belief that one day, the state will no longer hold the nation hostage.

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]

VPNovaya

Help Russians and Belarusians Access the Truth