On Tuesday, the yield on the 10-year Treasury surged nearly 10 basis points in a few hours, rising above 4.49 percent. The rising yield came after the release of new price-inflation data showing that CPI growth had hit a five-month high and remained well above the Federal Reserve’s two-percent target for price inflation. Rising yields often indicate that bond investors believe price inflation will continue to grow, so it was probably no coincidence that bond yields—especially on longer-term bonds—jumped following the report’s release.

Whatever the reason behind the rising yield, this is bad news for those who were looking for a good reason to believe that mortgage rates will significantly fall again soon. Mortgages for single-family homes closely follow the 10-year yield, and, as the 10-year yield has risen in recent years, the average 30-year mortgage more than doubled. Ity rose from under three percent in mid 2021 to above seven percent by late 2023. It has remained above six percent ever since.

Meanwhile, home prices continued to rise well into mid 2025. This combination of rising home prices and rising mortgage rates has made housing unaffordable for a growing share of propsective homebuyers.

In response to this trend, The Trump administration’s FHFA Director, Bill Pulte—a scion and nepo baby from a wealthy family of homebuilders—has demanded that the central bank intervene to force down mortgage rates in order to stimulate residential home sales and home prices. Pulte claims that Fed chairman Jerome Powell’s lack of enthusiasm for lowering interest rates is “the main reason” that there is not more home-sales activity. Pulte concludes that Powell is “hurting the mortgage market” by “improperly keeping interest rates high.” Pulte apparently believes that more people would buy homes if only the Fed fixed the situation with lower interest rates.

When the Fed intervenes to lower interest rates, monetary inflation is required. To demand lower interest rate policy—as Pulte is doing—is to demand more inflation. At the core of this inflationist position is the misconception that rising home prices—and their negative effect on homeownership—can somehow be “fixed” or rendered irrelevant by lower interest rates. This is not how things work, however. Even if mortgage rates were to go down again, rising prices mean homeowners would still be stuck with higher costs and higher property taxes that result from rising prices. Moreover, Pulte is wrong to even assume that Fed intervention via the policy interest rate would somehow, magically, bring down 30-year mortgage rates.

Problems with Rising Home Prices

Last week, we explored the many ways that the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy and asset purchases have fueled rising home prices. There is a close correlation between the central bank’s purchases of mortgage backed securities, the falling federal funds rate, and rising home prices. Falling interest rates have fueled rising home prices. This has led to historic lows in the affordability of homeownership, and a rising average age for home owners.

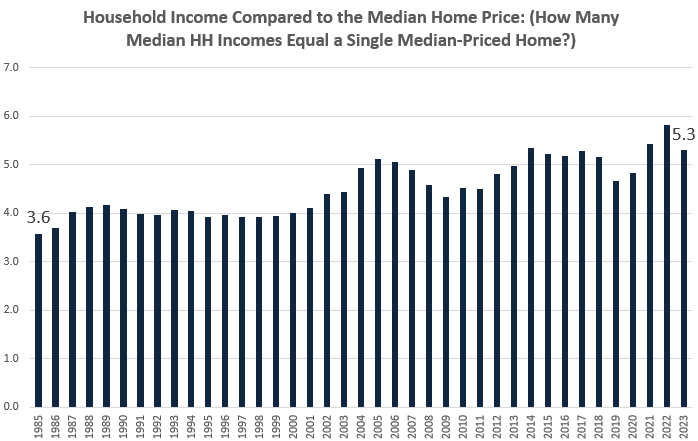

As home prices have risen, homes have become less affordable. Notably, the median home price has become much larger over time, when compared to the median household income. In 1985, for example, the median home price was 3.6 times the size of annual median household income. By 2023, the median home price was 5.3 times the median household income.

Rather than address the larger issues of asset-price inflation fueled by easy money, advocates of central planning, like Pulte, insist that the best way to “solve” the problem is to have the central bank somehow force down mortgage rates.

Assuming that the central bank has the power to do this, would it make housing more affordable? In certain ways, yes. If the only measure of affordability is the size of the monthly mortgage payment, then lower mortgage rates, all else being equal, make home purchases more affordable. For example, a $500,000 loan at 3% for 30 years will require a monthly payment (on principle and interest) of about $2100. On the other hand, the same loan at 6% will require a monthly payment of nearly 3,000 per month.

But, monthly costs associated with a home purchase do not consist of only payments on a loan’s principal and interest. Homeowners must also pay property taxes and insurance. Home buyers must also come up with down payments which, of course, are proportional to the home price. Thus, home-price inflation leads to higher down payments while also driving up property taxes—which are also tied to the home price. The monetary inflation that underlies rising home prices also tends to inflate the price of services like homeowner’s insurance. Principal and interest may be fixed in a 30-year mortgage, but taxes and insurance—which increase with price inflation—are not fixed. Thus, these costs are certainly not made irrelevant by falling interest rates.

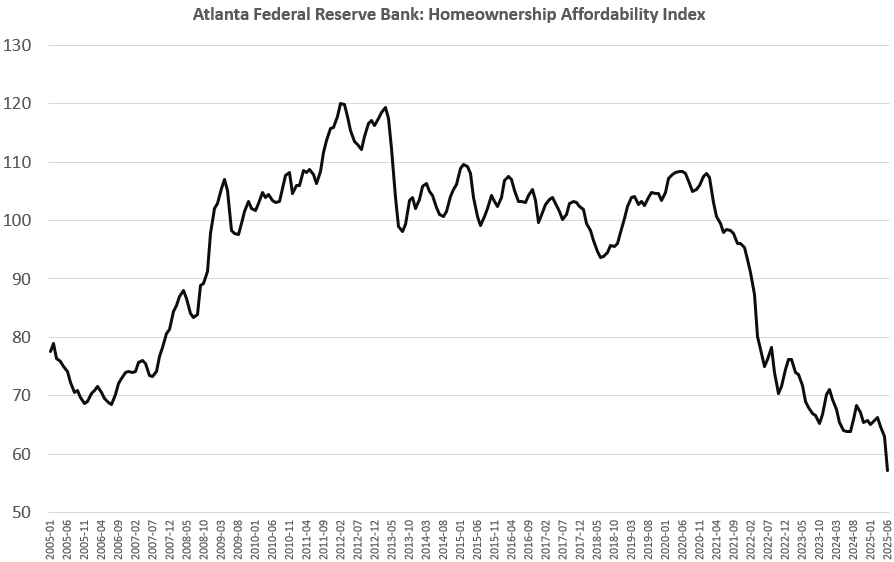

It is not surprising that, as home prices increased in the wake of the covid panic’s runaway monetary inflation, the Atlanta Fed’s affordability index plummeted to historic lows.

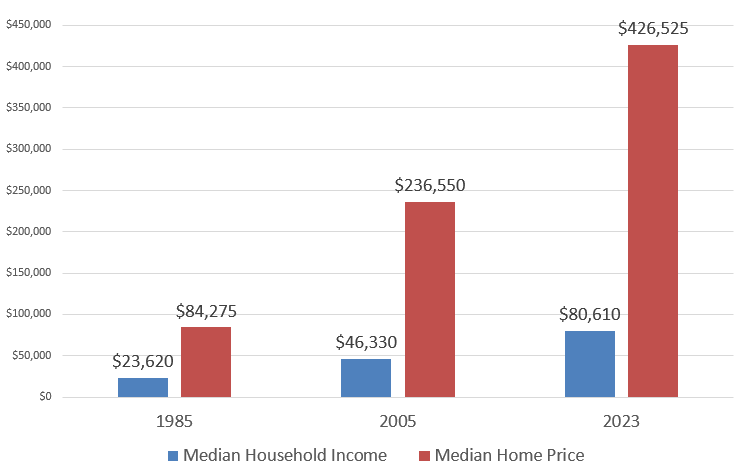

We can partly see why this happened if we compare prices and income over time. In 1985, for example, the median home price was about $81,000, but rose by 406 percent to about $426,000 in 2023. Obviously, any taxes, insurance, and down payments that are proportional to the home price were far lower in 1985 than they are now. Moreover, as home prices quintupled from 1985 to 2023, median household income only increased by 241 percent, rising from about $23,000 in 1985 to $84,000 in 2023.

These rising prices took their toll on affordability, even as interest rates were falling. For example, from 2006 through 2021, the average mortgage rate fell consistently. Yet, during most of that period, the affordability index only moved sideways.

Moreover, this proved to be unsustainable. The problem with constantly falling interest rates is that, eventually, they get so low that there’s not room to move downward. In 2021, mortgage rates were at or near all-time lows. Yet, the very small uptick in average mortgage rates that occurred from 2021 to 2025—with rates still below historically normal levels—caused affordability to collapse.

So, Pulte is simply wrong if he’s claiming that the Fed would increase the affordability of homes if only Jerome Power would intervene to force down mortgage rates.

Does the Fed Have the Power to Reduce Mortgage Rates?

Finally, we have to ask ourselves if the Fed even has the ability to somehow force down mortgage rates by lowering the Fed’s policy interest rate. It appears that this may be possible some of the time. For example, from 2008 to 2022—a period when bond investors showed little concern over deficits or price inflation—both long-term and short-term yields declined as the Fed cut the target policy interest rate.

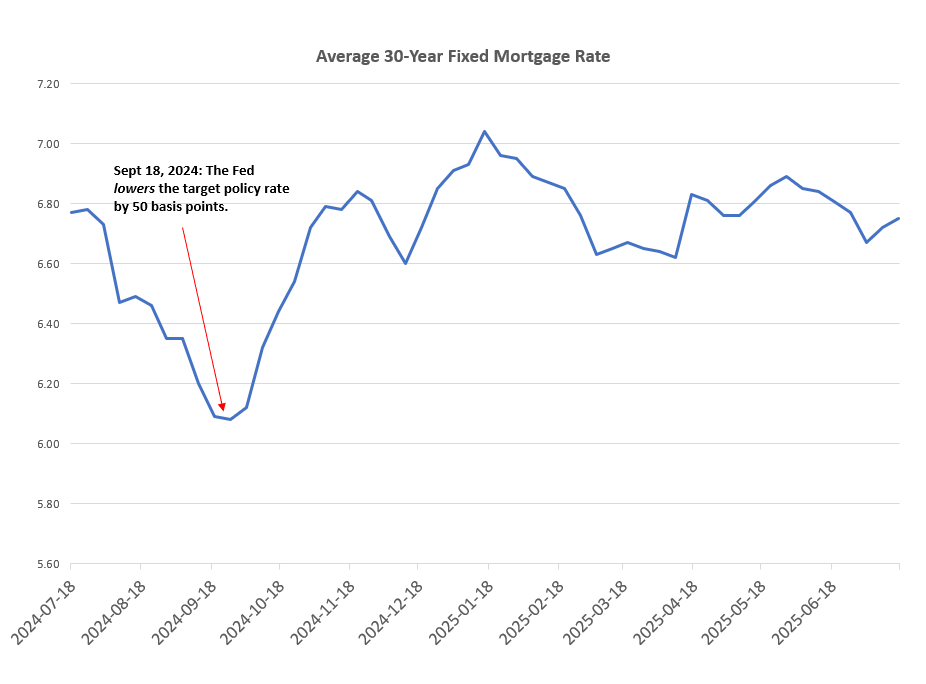

Those days, however, appear to be over. For example, when the Fed cut the policy rate in September of last year, the average mortgage rate increased. In the wake of the Federal Reserve’s extreme monetary inflation of 2020-2021, and as federal deficits continue to mount bond yields are likely to increase if the Fed tries to embrace a new easy money stance pushing lower interest rates.

Not only is Pulte wrong that falling mortgage rates necessarily make homeownership more affordable, he is also probably wrong that the Fed can reduce those rates by targeting a lower policy rate. If Pulte really wanted to see homes become more affordable, he would push for less monetary inflation and for lower federal deficits. He would push for the Fed to reduce its balance sheet of mortgage backed securities. All that, however, would lead to falling home prices, and that would run afoul of the administration’s Wall Street allies who incessantly demand more asset price inflation.