William H. Vanderbilt—who appears in Bartlett’s Quotations for “the public be damned”—is the only person in US history whose father (Cornelius, or “the Commodore”) was, for a time, the richest person in the country, and who was himself, for a time, also the richest person in the country.

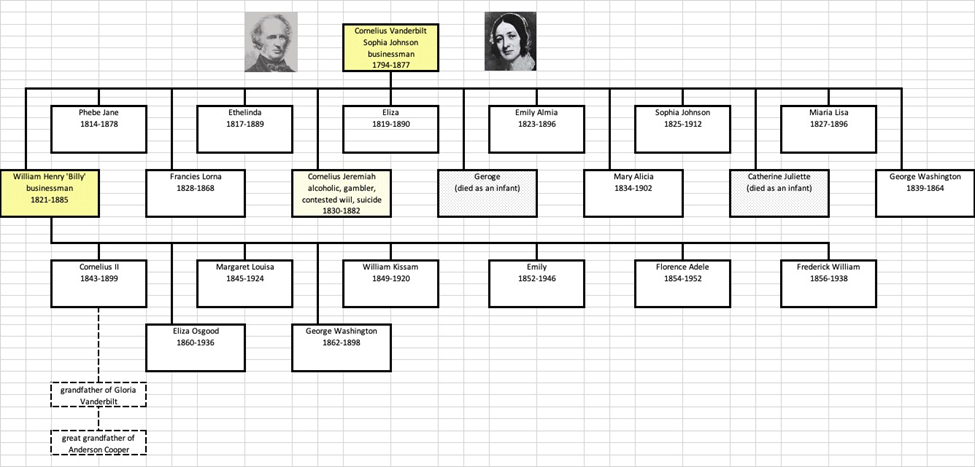

Of the Commodore’s two adult male children, one (in the dark yellow in the below chart) appeared to be cut from the same mold as he, and the other (light yellow), a wastrel. The Commodore left each of his surviving children a fortune; and, he left the overwhelming portion of his vast estate to William H., known within the family as “Billy.”

Consolidating and expanding on the New York Central railroad, Billy quadrupled his inheritance. He became one of the country’s first billionaires (in today’s money). He, his siblings, and their children proceeded to mansion-building and, in other ways, to live large. Only a few of them entered business.

Within a hundred years, the Vanderbilt fortune was dissipated. In 1973, when more than a hundred progeny gathered, not one was a millionaire (in the money of that day). In 2021, Anderson Cooper—son of Gloria Vanderbilt—published a book, Vanderbilt: The Rise and Fall of an American Dynasty.

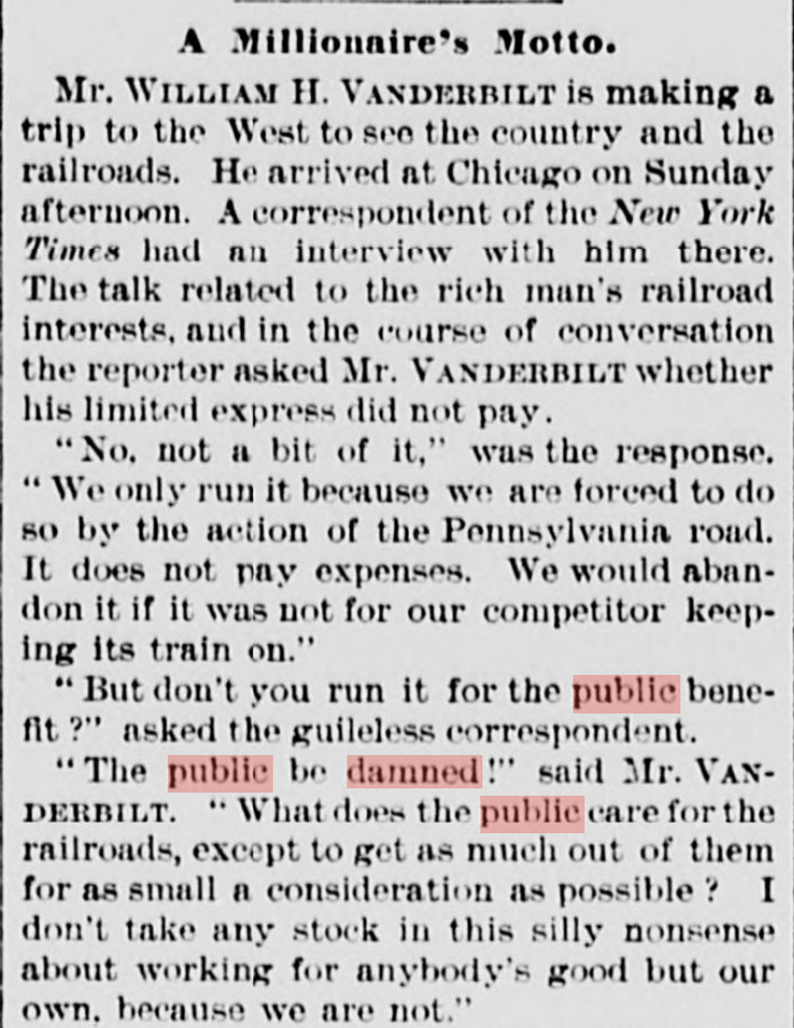

According to one account, William H. Vanderbilt said “the public be damned” during an interview with reporters aboard a Chicago-bound train on October 7, 1882. A reporter asked whether his limited express trains pay or were run for the accommodation of the public? “Accommodation of the public?” replied Vanderbilt, “The public be damned!”

Here is how this incident was reported in the New York Sun of October 10, 1882 (p. 2):

Vanderbilt denied uttering the specific words, but his denial rang hollow because of his imperious attitude. Besides, what Vanderbilt said was completely valid, whether or not it was impolite. The New York Central was run for the benefit of its shareholders, not for the benefit of its riders.

At the time, the New York Central was in competition with the Pennsylvania RR for the prestigious New York to Chicago passenger route. The route was a showcase and—on each railroad—featured the best locomotives, well-appointed cars, and luxurious service.

Two decades later, the New York Central initiated the 20th Century Limited, running from Grand Central Station in New York City to LaSalle Street Station in Chicago. The 20th Century Limited would be the most profitable route of the New York Central. But, at the time of the interview, twenty years prior, the route lost money according to Vanderbilt. So why did the New York Central offer the service? There’s a sense in which the profitability of the route was irrelevant. It was run at a loss because the attention it attracted to the New York Central brought enough other business.

For one thing, there’s an old rule of thumb in railroading that you lose money on twenty percent of your lines. These money-losing lines wind up to be feeder lines for the profitable lines of the network. Actually, that’s only the way the numbers come out according to the accountants. Good businessmen sometimes have to see beyond the accounting figures to take into account inter-relations among their company’s products and services.

The same could be said of first-class service on the great ocean liners of the late 19th century. Similarly, top of the line models of car manufacturers come the next century. Indeed, famous basketball players might be paid to wear branded athletic shoes; and, fashion designers might compete to attire celebrities for marquee events. Come Thanksgiving, supermarkets might take a loss selling the turkey in order to generate sales of the trimmings. Business decisions often involve such complexities, but this doesn’t mean business isn’t focused on the bottom line.

Returning to William H. Vanderbilt, he was not a salaried man. His income was from dividends on his stock. His working on behalf of the shareholders of the New York Central coincided with his working for himself. This arrangement was facilitated by his inheritance. However, few people combine such a large inheritance with the talent and ambition needed to greatly expand on their fortune. Most people with large inheritances are too comfortable for the rough and tumble of business. Hence, Vanderbilt’s uniqueness as a son of a person who was for a time the wealthiest man in the country, who himself became for a time the wealthiest man in the country.

We have some key owners of corporations today, such as Jeff Bezos of Amazon and Elon Musk of SpaceX. These key owners can be trusted by other shareholders because of their personal incentive for their companies to be profitable. But, mostly, corporations have to motivate managers who are not already wealthy to work on behalf of shareholders. Corporations do this mostly with management stock options. Raising the value of the firm can make managers with such stock options enormously wealthy. There are some problems with management stock options, but usually management stock options align the motivation of managers with the interests of shareholders.

Who do corporate managers work for the customers or the shareholders of their companies? We can correctly say that maximizing the value of the firm usually involves attending to all the firm’s stakeholders, including its customers. Thus understood, stakeholder capitalism is unexceptional. But, many who advocate stakeholder capitalism want to push attention to non-shareholder stakeholders beyond the limits of value maximization. No, value maximization should guide stakeholder capitalism. Even so, it isn’t advisable to say, “the public be damned.”