Tariff advocates John Carney and Alex Marlow wrote a Breitbart Business Digest article, citing various statements from the Federal Reserve’s August Beige Book to support their argument that heightened consumer price-sensitivity is forcing American businesses to absorb tariff costs:

After years of Bidenflation and real wage reductions, consumer financial strain has reached levels where price increases trigger immediate demand destruction. A Philadelphia contact reported that “more than half of their customers have become more price sensitive since the prior quarter.”

The result is businesses facing a stark choice: raise prices and lose customers or absorb costs and accept lower profitability. Many are choosing the latter.

The authors go on to suggest that there are three significant consequences of this alleged cost absorption by American businesses:

Muted Consumer Inflation: Despite significant tariff increases, consumer prices haven’t risen proportionally because businesses are absorbing much of the impact.

Profit Margin Pressure: Companies across sectors are turning to improved efficiency and headcount reduction to maintain profitability as they choose market share preservation over raising prices.

Tight Money: The inability to pass through costs is itself a sign that monetary policy is significantly restrictive.

While this analysis sounds superficially plausible, there is an egregious economic fallacy at the heart of it. Businesses can neither “absorb costs” nor knowingly “accept lower profitability” and expect to stay in business for very long. Businesses voluntarily bear costs only because they expect to earn even greater revenues in the future from the productive activities that bearing those costs make possible.

The investment of savings in a productive activity itself has an important cost associated with it—a given investment in production inputs makes sense only if the prospective rate of return is sufficient to compensate investors (both the shareholders and creditors of the businesses) sufficiently for tying up their purchasing power over time and for the uncertainty associated with realizing those prospective returns. A reduction in a business’s profitability prompts investors to invest their savings in something else instead or to stop investing altogether if all businesses are afflicted with such profitability losses. Instead of absorbing increased costs, a revolt by investors always forces businesses to cut such costs as quickly as possible. The subjective time and uncertainty preferences of savers are just as unforgiving as the subjective preferences of consumers are.

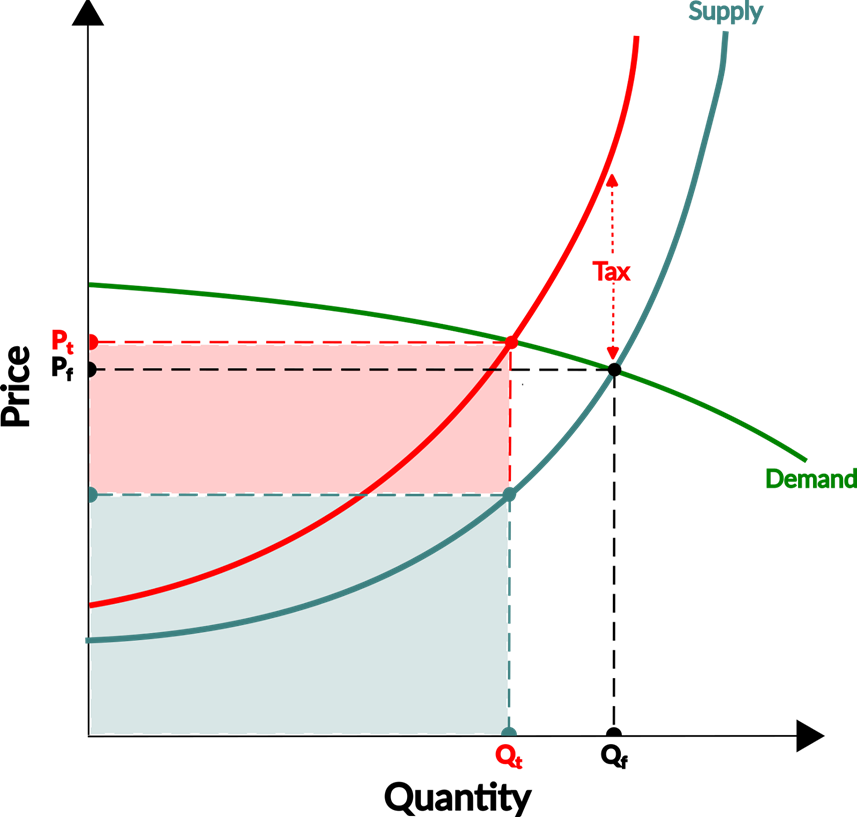

So what are we to make of the muted consumer price increases and the August Beige Book reports of profitability losses? To understand what is going on here, figure 1 below is a supply and demand graph illustrating what happens when an indirect tax like a tariff is imposed and consumers happen to be price-sensitive. High consumer price-sensitivity means that the demand curve (shown in green) has a relatively shallow downward slope—even a small increase in price results in a large decrease in the quantity of goods consumers are willing to purchase.

The upward-sloping supply curve (shown in blue) reflects the quantity of goods businesses can offer to sell at each given price without suffering losses. It reflects the situation where prices are in balance with costs, including the costs of time and uncertainty borne by investors as well as the costs of wages paid to workers, the costs of acquiring goods from earlier stages of production (e.g., the costs of overseas manufacturing, the costs of shipment, etc.), etc. The crucial point to understand here is that businesses can’t shift either the blue or the green curves confronting them. What a government can do, however, is increase the overall cost of providing a good by imposing a tax on it, shown by the red curve. The additional tax on each unit of the good appears here as the difference between the red and the blue curves.

Figure 1: Supply/demand effects of indirect taxes with price-sensitive consumers

Source: Vincent Cook

In a free market, the price charged (Pf) and quantity sold (Qf) will tend to move towards the intersection of the green and the blue curves. While the curves are themselves always changing over time, the emergence of profits or losses will always compel businesses—even when they fail to correctly anticipate such changes—to adjust the quantities they sell back towards Qf and the prices they charge back towards Pf. Anyone who foolishly absorbs costs with no prospective reward in sight will dissipate their capital and eventually go out of business if they don’t change their spendthrift ways.

Once a tariff or other indirect tax is imposed and businesses have fully adjusted their structure of production to the new situation, the intersection between the red and green curves dictates a new increased price Pt and a new decreased quantity Qt. Since we have kept the slope of the green curve fairly shallow, the resulting price increase is indeed muted—Pt is not much higher than Pf. Pt is also a great deal lower than the sum of Pf plus the tax, contrary to what one might naively assume by simply applying the tariff rate to the previous free market price.

However, another consequence of the shallow-sloped green curve is that we get some fairly significant demand destruction—Qt is substantially less than Qf. Cutting costs doesn’t mean that tariff-burdened businesses are “preserving market share” when they lay-off workers, etc. to mitigate price increases. On the contrary, it means that they are significantly reducing the quantity of goods they can sell going forward.

Another thing we can glean from this graph is what happens to business revenues. In the free market case, the total revenue received by businesses equals the product of price and quantity, which corresponds to the area of the rectangle bounded by the black dashed lines (i.e., the area bounded by Pf and Qf). Once the tax is imposed, however, the total revenue (now the area of the rectangle bounded by Pt and Qt) is reduced as a consequence of the shallowness of the green curve. Moreover, the total revenue is divided between the government (which gets an amount corresponding to the area of the red-shaded rectangle) and the businesses (which get an amount corresponding to the area of the blue-shaded rectangle).

Comparing the area of the rectangle within the black dashed lines to the area of the blue rectangle, it is not hard to visualize why businesses that sell imported goods might be under such enormous pressure to cut costs, as their revenues are being absolutely crushed by the combination of steep tariffs and price-sensitive consumers.

When applying such a theoretical supply/demand analysis to the reports in the August Beige Book, we must bear in mind that markets haven’t fully migrated to the new long-run Pt and Qt values yet. A few months ago it was possible for some businesses to partially mitigate their future tariff costs temporarily by building up their inventories ahead of the imposition of tariffs. Thus, for many imported goods the full extent of the reductions from Qf to Qt and increases from Pf to Pt haven’t been realized yet. For some goods, there are intermediate values of P and Q we are now experiencing that reflect the effects of relatively modest storage costs, which are not nearly as severe as the future effects of tariffs might be. We do not yet know the true magnitude of either the demand destruction or the price increases that steep tariff increases will ultimately cause.

Even so, it does appear that significant cost cutting has been taking place already. Though demand destruction hasn’t fully kicked in yet, the Beige Book reports hints that it will—workers are already losing their jobs and other costs are already being cut aggressively in anticipation of future decreases in sales of imported goods. Such severe profit margin pressure is certainly no cause for celebration by either workers or consumers.

What is less certain is what will happen to prices thanks to President Trump’s tariff-induced supply shock—as inventories of imported goods are exhausted, we may start seeing shifts of expenditures to domestic goods, driving their prices up significantly. Moreover, we may see significant changes in the types of goods purchased with different categories of goods having prices moving in different directions, rendering consumer price indices ineffective as measures of the dollar’s purchasing power. It is too soon to be celebrating how muted price increases have been so far.

As for monetary policy, money creation can’t mitigate the cost-cutting pressures induced by the combination of steep tariffs and heightened consumer price-sensitivity. A looser monetary policy would raise costs of inputs (including tariff costs) as well as raise the prices of outputs sold to consumers, so the relative shapes and locations of the supply and demand curves aren’t likely to change much relative to each other except to the extent that supply is forced upwards relative to demand due to the effects of wasteful boom/bust cycles, of deterrence of thrift by artificially-low interest rates, and of losses of confidence in the dollar.

Once we dispose of the cost-absorption fallacy, promoted by Carney and Marlow, we can’t avoid the conclusion that tariff burdens are harmful even if that harm has not been manifested (at least not yet) in increases in price index levels.