During the savings and loan crisis in the 1980s and 1990s, an interesting exchange took place on The Phil Donahue Show that is representative of a few collectivist category errors. The exchange was reported in the Washington Post on June 4, 1989 and the topic of discussion concerned the billions that the crisis would cost taxpayers. One man indignantly asked, “Why can’t the government pay for these debts instead of the taxpayer?” This question was cheered by a crowd of several hundred in the angry audience. Donahue responded, “Because we are the government… It’s going to be our money.” Donahue was right about one thing—the American taxpayer would certainly pay.

In the first case, the angry questioner overlooks the source from which government gets its revenue before it pays for anything—coercive taxation. On the other hand, Donahue—though he is right to acknowledge that when the government pays, we pay—makes another category error by equating the people with the political caste in the government: “we are the government.”

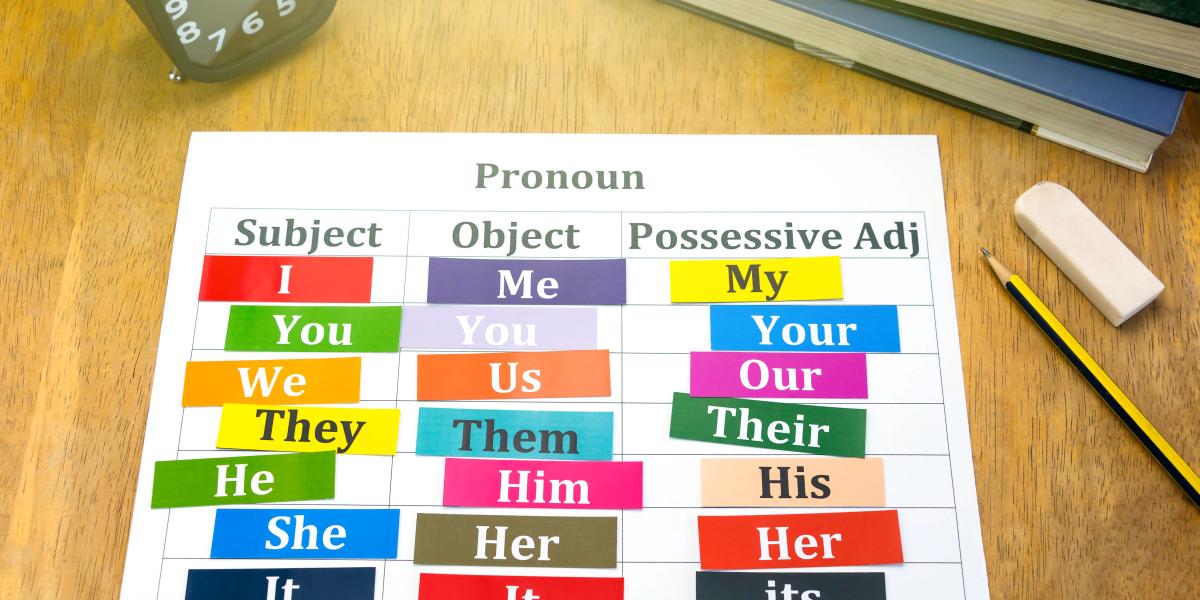

In general, it is easy to use collective pronouns—“we,” “us,” “our,” etc.—which is often understandable and appropriate depending on context, but such language is often used to speak of an entire “people” or even the actions of the political state. This sloppy abstraction not only obfuscates truth but it trains people to think in collective terms in which the state and its actions come to be synonymous with “society,” “the people,” “the common will,” “the common good,” “we,” “us,” “our,” or other euphemisms.

This is especially the case in a so-called “democracy” but is not exclusive to this format of government. (This is true whether it is literally direct democracy, representative democracy, or where the term acts as a terminological stand-in for the sacred institutional establishment that allows citizens to vote on aspects of how the regime operates.) Democracy—rule by the people—has, of course, existed since ancient times, however, it has become especially prevalent since World War I. Among the states of the world, about 74 are regarded as democracies (either partial or full). Even some of the most authoritarian regimes at least want the appearance or name of democracy because democracy is regarded as an unqualified good by many, especially in the modern West. This paradigm allows governments—whatever their actions—the convenient claim that its people are the government, therefore, whatever the state elites do has been pre-legitimized by the people.

This mindset allows coercive state intervention to be more subtle, even defended and praised by its people. With this mindset, people take criticisms of government or policy personally as a criticism of them. This often manifests on the political left and right. On the left, often bad government actions or policies are used to get people to hate “America” instead of the state. On the right, criticism of government actions or policies is often said to be criticism of “America,” but, also on the right, the good will that Americans often have toward America is often borrowed to excuse the state. The left, again—even more prone to a collectivist mindset—continually group people collectively, which is why they can associate a white man in Ohio in 2025 with the actions of Columbus, for example.

Murray Rothbard shrewdly identified how the use of certain pronouns—“we,” “us,” “our,” etc.—mask the actions of the political caste, its enforcers, and its net beneficiaries. Further, this language tends to subtly legitimize past, present, or future actions of the state. He wrote,

With the rise of democracy, the identification of the State with society has been redoubled, until it is common to hear sentiments expressed which violate virtually every tenet of reason and commonsense such as, “we are the government.” The useful collective term “we” has enabled an ideological camouflage to be thrown over the reality of political life. If “we are the government,” then anything a government does to an individual is not only just and untyrannical but also “voluntary” on the part of the individual concerned.

Bastiat also recognized this conflation between the state and society. This association gives an undeserved bad name to society and many other other things and an undeserved good name to the state. Regarding the illusion of voluntarism with “democracy,” it should be pointed out that a voter in a minority—whether he votes yes, no, or refrains from voting—gets the same results and is said to have consented to the system or has forfeited the right to complain. In a representative democracy within a state system (i.e., not voting voluntarily where to eat with friends), even if an elected representative only had to represent two people, and only those two, he must choose between representing and not 50 percent of his constituency if they are diametrically opposed on an issue. The larger a population is in a democracy, the less say each voter has, and there is no guarantee that those elected will carry out the will of the voters who voted for them. Rothbard provides some striking examples of this logic, which bring to mind the childish phrase “why are you hitting yourself?”,

If the government has incurred a huge public debt which must be paid by taxing one group for the benefit of another, this reality of burden is obscured by saying that “we owe it to ourselves”; if the government conscripts a man, or throws him into jail for dissident opinion, then he is “doing it to himself” and, therefore, nothing untoward has occurred. Under this reasoning, any Jews murdered by the Nazi government were not murdered; instead, they must have “committed suicide,” since they were the government (which was democratically chosen), and, therefore, anything the government did to them was voluntary on their part. One would not think it necessary to belabor this point, and yet the overwhelming bulk of the people hold this fallacy to a greater or lesser degree.

Following the Philadelphia Convention (1787) and during the period of ratification, this was a similar concern from opponents or skeptics regarding the new Constitution. If the new federal-national government could speak in the name of “We the People”—though it originally said “We the States,” but was changed because ratification by all states was not guaranteed—who could possibly question its legitimacy or actions? This might grant political elites in the constitutional government—whether elected or not—superior and unquestionable powers. Were a single state—more specifically, individuals within the state—to object, their wills could easily be overridden by the national government which allegedly represents all the people. This would mean that the cause of the recent American Revolution—state secession and independence from Britain—would now be abandoned, making the states and people within them subject to a political elite in a US government that now had the unique ability to speak in the name of “the People.” On June 4, 1788, Patrick Henry—a key opponent of the ratification of the new Constitution—objected in his opening speech at the Virginia Ratifying Convention,

Sir, give me leave to demand, what right had they to say, “We, the People”…. Who authorized them to speak the language of ‘We, the People,’ instead of “We the States”? States are the characteristics, and the soul of a confederation. If the States be not the agents of this compact, it must be one great consolidated National Government of the people of all the States. . . . The people gave them no power to use their name. (Patrick Henry, as quoted in Bernard Bailyn, ed., The Debate on the Constitution, Part Two (New York: Library of America, 1993), p. 596, emphasis added)

Similarly, the famous Samuel Adams said in letter to Richard Henry Lee on December 3, 1787,

I confess, as I enter the Building [the Constitution] I stumble at the Threshold [the Preamble: “We the People…”]. I meet with a National Government, instead of a Fœderal Union of Sovereign States. I am not able to conceive why the Wisdom of the Convention led them to give the Preference to the former before the latter. If the several States in the Union are to become one entire Nation, under one Legislature, the Powers of which shall extend to every Subject of Legislation, and its Laws be supreme & controul the whole, the Idea of Sovereignty in these States must be lost.

Even Mikhail Bakunin—an anarchist contemporary of Marx who broke with Communism because he saw it concentrating power in the state and merely replacing one ruling elite with another in the name of “the People”—gave a poignant warning,

Besides, the State…is by its very nature a great sacrificer of living beings, It is an arbitrary being in whose heart all the positive, living, unique, and local interests of the people meet, clash, destroy each other, become absorbed into that abstraction called the common interest or the common good or the public welfare, and where all the real wills cancel each other in that abstraction that bears the name will of the people. It follows from this that the so-called will of the people is never anything but the negation and sacrifice of all the real wills of the people, just as the so-called public interest is nothing but the sacrifice of their interests. But in order for this omnivorous abstraction to impose itself on millions of men, it must be represented and supported by some real being, some living force. Well, this force has always existed. In the Church it is called the clergy, and in the State the ruling or governing class.

In other words, Bakunin warned that when state elites justify their actions as “the will of the people,” it is just an abstraction for the will of certain state elites, conveniently masquerading as effectively representing the will of the people. Therefore, when the state cancels out the wills of real people or violates the rights of real individuals, then it is still legitimate because those doing it are doing so in the name of the whole people. In fact, since “we are the government,” these people are doing it to themselves.

It is key to remember a key fact: “We must, therefore, emphasize that ‘we’ are not the government; the government is not ‘us.’” Therefore, in this instance, Rothbard emphasizes careful use of pronouns.