Why do individuals value bread less than gold, when bread seems to be more important in supporting an individual’s life than gold? To provide an answer to this question, economists refer to the law of diminishing marginal utility.

Mainstream economics explains the law of diminishing marginal utility in terms of the satisfaction that one derives from consuming a particular good. For instance, an individual may derive vast satisfaction from consuming one cone of ice cream. However, the satisfaction he will derive from consuming a second cone might also be great but not as great as the satisfaction derived from the first cone. The satisfaction from the consumption of a third cone is likely to diminish further, and so on.

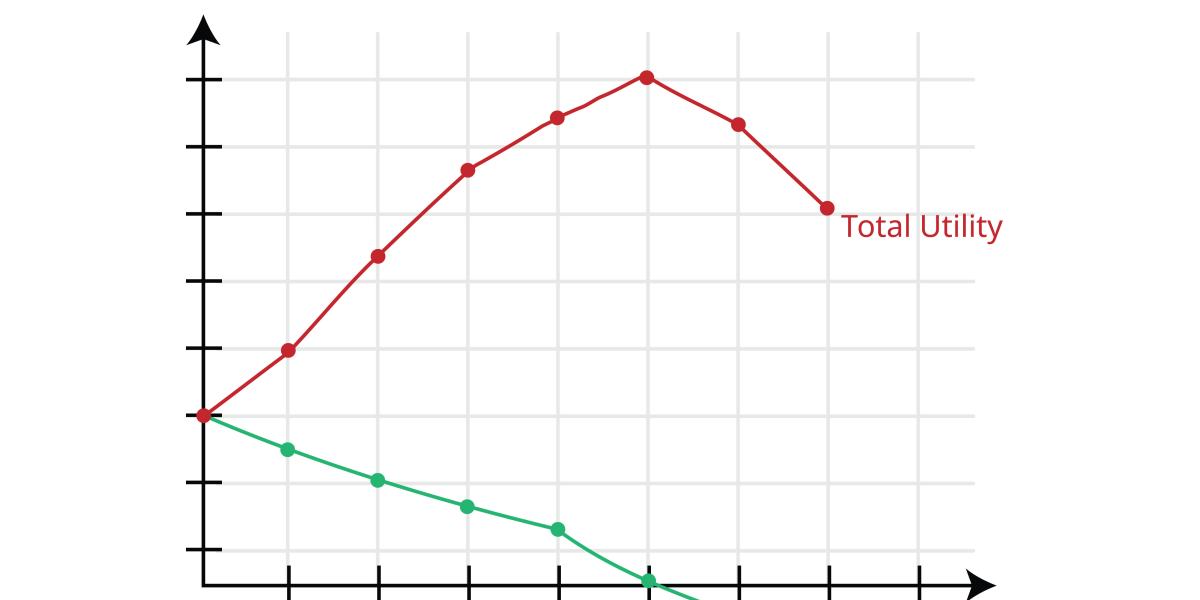

From this, mainstream economics concludes that the more of any good we consume in a given period, the less satisfaction, or utility, we derive out of each additional, or marginal, unit. From this, it is also held that if the marginal utility of a product declines as we consume more and more of it, the price that we are willing to pay per unit also declines. Now, according to the mainstream framework, since gold is relatively scarcer than bread, it follows that the price of gold should be higher than the price of bread because the marginal utility derived from bread will be much lower than the marginal utility derived from gold.

Utility, in this paradigm, is presented as a certain quantity that increases at a diminishing pace as one consumes or uses more of a particular good. Given that utility is presented as some total quantity—also called total utility—it becomes possible to introduce mathematics here to ascertain the addition to this total. However, does it make sense to discuss the marginal utility of a good without referring to the purpose that this good serves?

Menger’s Explanation

According to Carl Menger—the founder of the Austrian School of economics—individuals subjectively assign priorities to the various goals that they wish to achieve. As a rule, according to Menger, various ends that an individual will find valuable will be assigned a descending rank in accordance with his own preferences. Further, as a quantity of a valued good increases, its marginal utility decreases per unit.

Consider John the baker, who has produced four loaves of bread. The four loaves of bread are his resources or means that he employs to attain various goals. Let us say that his highest priority or his highest end is to have one loaf of bread to eat. The second loaf of bread helps John to secure his second most important goal— exchange for five tomatoes. John uses a third loaf of bread to exchange it for the third most important end—a shirt. Finally, John decides that he is going to allocate his fourth loaf to feed wild birds. Thus, here is how John’s subjective preferences relative to loaves (units) of bread:

- Bread to eat;

- Bread to exchange for five tomatoes;

- Bread to exchange for a shirt;

- Bread to feed wild birds

Were one of the loaves (units) of bread to be lost or destroyed, which end would John give up first? By his action, assuming that his preferences have not changed, we would see that John would give up feeding the birds—his lowest-ranked preference for a unit of bread at that moment. Conversely, the law of marginal utility means that as marginal units of a good increase, its marginal utility decreases.

Ends Determine the Value of Means

A given end dictates the specific scarce means chosen by individuals for the attainment of that goal. The ends determine the means. In the above example concerning loaves (units) of bread, each unit of bread served a different end or goal. The subjective preferences of John and the greater or lesser availability of units of the good determined each use for each unit of bread. Therefore, there is no such thing as total utility. The end satisfied by the first loaf of bread—satisfying hunger—carries much ordinally higher importance than the second loaf because the second and lower ends are less valuable.

Thus, even though water, for example, is necessary for life, we observe that it is often cheap due to its abundance. As the marginal units of water increase, the marginal utility for each unit of water decreases and the price decreases.

The Value of Each Unit of Goods is Determined by the Least Important End

Since John regards each of the four loaves of bread in his possession as homogeneous units, he assigns to each loaf of bread the importance imputed from the least important end (feeding wild birds). Why does the least important end serve as the standard for valuing the loaves of bread? The answer is because, as the marginal units of goods increase, the marginal utility of each unit decreases, which means that marginal utility is determined by the lowest end the available stock of goods will satisfy.

Imagine if John used the highest end—feeding himself—as the standard for assigning value to each loaf of bread. This would imply that he values the second, third, and the fourth loaves much higher than the ends he secures with them. However, if this is the case, what is the point of trying to exchange something that is valued more for something that is valued less? If a loaf of bread is valued by John higher than five tomatoes obviously, no exchange will take place.

Since the fourth loaf of bread is the last unit in John’s total supply it is also called the marginal unit (i.e., the unit at the margin). This marginal unit secures the least important end. Alternatively, we can also say that the marginal unit provides the least benefit. If John had only three loaves of bread, each loaf would be valued according to the end number three—the shirt. This end is ranked higher than the end of feeding wild birds, but lower than the others. From this, we can infer that as the supply of bread declines, the marginal utility of bread increases. This means that each loaf of bread will be valued much higher now than before the decline in the supply of bread. Conversely, as the supply of bread rises, its marginal utility falls, and each loaf of bread is now valued less than before the increase in the supply took place.

Furthermore, marginal utility here is not as the mainstream perspective presents—an addition to the quantifiable total utility but rather the utility of the marginal end. Utility is not about quantities, but about priorities or the ranking that each individual sets on a good relative to the end that it serves. According to Rothbard,

Many errors in discussions of utility stem from an assumption that it is some sort of quantity, measurable at least in principle. When we refer to a consumer’s “maximization” of utility, for example, we are not referring to a definite stock or quantity of something to be maximized. We refer to the highest-ranking position on the individual’s value scale. Similarly, it is the assumption of the infinitely small, added to the belief in utility as a quantity, that leads to the error of treating marginal utility as the mathematical derivative of the integral “total utility” of several units of a good. Actually, there is no such relation, and there is no such thing as “total utility,” only the marginal utility of a larger-sized unit. The size of the unit depends on its relevance to the particular action.

Now, in the mainstream approach, there is a strong emphasis on indifference curves, which are supposedly helpful in understanding individuals’ choices. Indifference, however, has nothing to do with individuals’ purposeful conduct. Individuals by pursuing purposeful actions cannot be indifferent between various goods. When confronted with various goods, an individual makes his choice based on the suitability of goods to be employed as means to various ends.

Conclusion

It does not make sense discussing the marginal utility of a good without referring to the purpose that a particular good serves. Marginal utility theory, as presented by popular economics, describes an individual without any goals and who is driven by psychological factors. In this sense, popular economics describes a mindless individual.