Few questions have divided liberals over the centuries more than the place of religion in a free society. Some have seen faith as irrelevant to liberty, a separate sphere best kept sealed off entirely from politics. Others have viewed it as the very enemy of freedom, pointing to centuries of clerical repression. Still others argued that religion was useful, a prop to social cohesion for a regime of limited government. Lastly, there was a bolder group that claimed that religion—particularly Christianity—is not just compatible with freedom but essential to it, historically and conceptually.

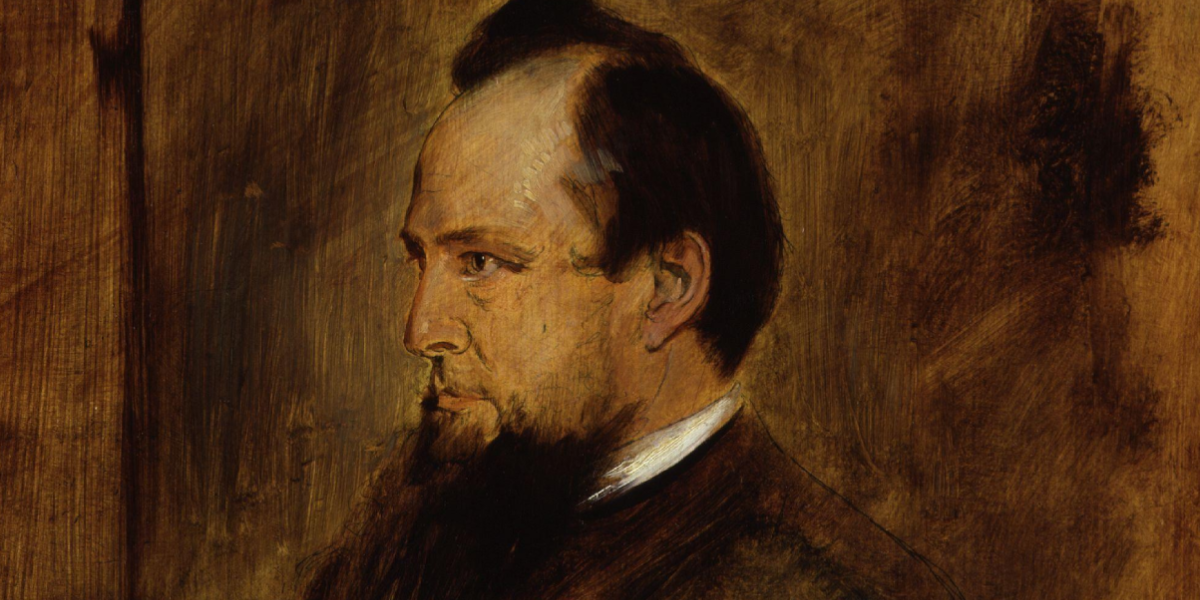

Ralph Raico, in his dissertation on The Place of Religion in the Liberal Philosophy of Constant, Tocqueville, and Lord Acton, insisted that this last position was correct and that it captures the heart of three of the 19th century’s most significant liberal thinkers. Of these, Lord Acton presents perhaps the most striking example: a Catholic aristocrat and Whig historian who believed that liberty without faith was doomed to collapse into materialism or relativism.

Acton’s Starting Point: Catholicism and Whiggism

Acton’s intellectual formation already signaled the tension that would run through his life. He was born into a Catholic family tied to the great Catholic aristocracies of the Continent, yet—through his stepfather—he was also linked to Britain’s Whig aristocracy. Under the influence of his teacher, the German theologian Ignaz von Döllinger, Acton immersed himself in the Catholic revival of scholarship in 19th century Germany. At the same time, he absorbed the Whig tradition of constitutional liberty.

The young Acton thought the two traditions need not clash. As Raico showed, Acton believed there was a “Catholic notion of the State” whose principles, properly understood, aligned with the English constitutional tradition. Only Catholicism, he suggested, could supply the metaphysical grounding for constitutionalism. “Only the true religion corresponds with the truth in politics,” he wrote, “else there is sure to be a break somewhere in the harmony.” For a time, he even described England and Rome as “the two great conservative powers.”

This synthesis reflected his admiration for Edmund Burke, whom he once called “the law and the prophets” of political thought. In Burke’s resistance to both the radicalism of the French Revolution and the abstract rationalism of Enlightenment philosophy, Acton saw an example of how Catholic sensibilities and constitutional liberty could reinforce one another.

Freedom as a Moral Order

Raico stresses that Acton’s philosophy of freedom was fundamentally moral and religious. Liberty was not one good among others, like wealth or happiness. It could not be traded off against progress or prosperity. For Acton, freedom was synonymous with the realization of moral order.

This set him apart from secular thinkers like Locke or Bentham. Locke had reduced liberty to the security of property, a “narrow” and “materialistic” conception that Acton believed missed the higher meaning of freedom. Bentham and the utilitarians—with their calculus of pleasure and pain—had no place for transcendent obligation. Acton, by contrast, argued that liberty is justified because it gives individuals the scope to fulfill their moral duties before God.

In this light, liberty is not the absence of restraint but the condition in which human beings can take responsibility for their actions. It is valuable not as a means to prosperity but because it sanctifies the moral life. Here, Acton’s Catholic faith provided the indispensable foundation: only a transcendent moral order could ground liberty’s unique dignity.

Christianity and the Historical Progress of Liberty

Acton also read history through this religious lens. Raico shows that he credited Christianity—especially Catholicism—with being the decisive force in the emergence of liberty. In classical antiquity, religion often bolstered tyranny rather than restraining it, and that it was only with the advent of Christianity that there came a moral order higher than the state.

Of course, the early Church did not always live up to this principle; many of the Fathers emphasized obedience to civil authority. But over time, Acton believed, the gospel’s insistence that allegiance to God came before allegiance to rulers gradually created a new respect for conscience. Christianity thereby placed a limit on state power by teaching that moral obligation transcends political authority.

This dynamic was evident, he argued, in 17th century England, where dissenting sects championed religious liberty and thereby advanced political freedom. They understood that their right to worship could only be secured by limiting the power of the state altogether. Acton contrasted this with Locke, whose defense of liberty was rooted in property, and with Hume, who carried Locke’s materialist perspective further. True liberty, Acton insisted, had been sanctified by religion, not secured by philosophy alone.

America, France, and the Higher Law

Acton’s reflections on the great revolutions of the 18th century further illustrate his point. He praised the American Revolution as the most important modern event for liberty, precisely because it rested on a commitment to the doctrine of higher law. Whether grounded in explicit religion or not, the belief that political authority must bow to transcendent norms gave the American cause moral force.

The French Revolution, by contrast, failed because it severed liberty from its religious roots. Its leaders appealed to reason, utility, or national will, but not to God’s law. In Acton’s eyes, the result was inevitable: liberty cut off from faith turned into tyranny and bloodshed.

Tensions and Contradictions

Raico is careful to note that Acton’s writings are not always consistent. Early in life he admired Burke as a Catholic-tinged conservative; while later he joked that he would have hanged Burke alongside Robespierre. His thought evolved from a genial Burkean traditionalism to a radical liberalism unique in its combination of Catholic conviction and Whig suspicion of power.

Moreover, Acton himself recognized the problem that modern liberalism was drifting away from religion. He once remarked that the liberal mind was marked by “extreme profaneness,” often deist or agnostic at best. Yet he never abandoned his conviction that without religion, liberty lacked its deepest justification.

Conclusion: Acton’s Relevance

Acton’s synthesis of Catholic faith and liberal politics may strike modern readers as paradoxical. Yet, as Raico shows, it was precisely this synthesis that gave his liberalism its depth. Where other liberals grounded freedom in property, prosperity, or utility, Acton rooted it in the eternal law of God. Religion, he believed, sanctified freedom, made men treasure the liberties of others as their own, and defended them not merely as rights but as duties of justice and charity.

In an age when secular liberalism often seems adrift, Acton’s example is striking. He reminds us that liberty without faith can easily become liberty without meaning. To preserve freedom, one must see it not simply as a tool for human enjoyment but as a calling of moral responsibility under God.

Raico’s portrait of Acton thus remains timely. It suggests that the relationship between religion and liberalism is not accidental or hostile, but essential and life-giving. If liberty is to endure, Acton warns, it must be sanctified—rooted in something higher than man, and in someone higher than the state.