Isaiah 1:22—“Your silver has become dross, Your drink diluted with water.”

Over 700 years before Christ, we read the above indictment of Israel’s southern kingdom of Judah from the prophet Isaiah. This principle—commanding just weights and measures and condemning dishonest scales—is reaffirmed several times throughout Scripture (Leviticus 19:35-36; Deuteronomy 25:13-16; Proverbs 11:1; 16:11; 20:10, 23; Hosea 12:7; Amos 8:5; Micah 6:10-11; Ezekiel 45:10). Part of the judgment involved the natural economic consequences of dishonest money through inflationary debasement and the consequent debasement of goods offered for sale in exchange for money, namely, food and drink.

The context provides every reason to believe that, not only were these practices society-wide, but were allowed and even encouraged by the civil rulers (Isaiah 1:23). At best, they benefitted from the corruption and did nothing to stop the fraud. These fraudulent and dishonest practices had consequences that pervaded their society, especially harming the honest, the innocent, and the vulnerable.

While monetary inflation has various economic effects—predictable and surprising, direct and indirect—this article seeks to explore the effects of monetary inflation on food. Specifically, debased currency leads to debased food and warps the structure of production such that options and behaviors are altered.

Others have noted this connection. Isaiah observed the connection between fraudulent silver debasement and product debasement some 2,700 years ago! Gary North, in his economic commentary, wrote concerning Isaiah 1:22,

Verse 22 points to the “drossification” of silver. This could refer to silver in general, or it may have been limited to the monetary unit. In either case, the legal issue was fraud by deception. That which was debased was circulating as something valuable. This produced analogous results. The wine was mixed with water. The debasement of silver, the metal of honesty and trade, had led to the debasement of a representative consumer good. Why? Because monetary inflation is based on deception. This deception then becomes universal as prices rise. Producers cut corners. The illusion of high quality products is maintained, just as the illusion of high quality money is maintained. In the modern phrase, “what you see is what you get,” no longer applied. What men saw was not what they got. They knew this, which was why Isaiah used the metaphor of dross. He knew they would recognize the connection. (emphasis added)

The closeness of the description indicates a single process, but, “What has silver got to do with wine?” Since money is economy-wide, monetary inflation is also economy-wide, affecting all sorts of goods, services, and choices. Saifedean Ammous, in his The Fiat Standard: The Debt Slavery Alternative to Human Civilization, writes (p. 111),

Money, being a part of every economic transaction, has a pervasive effect on most aspects of life…. [For example, take] two particular distortions: how fiat’s incentives for raising time preference affect farmland production and food consumption choices, and how fiat government financing facilitates an activist government role in the food market through interventionist farm regulations, food subsidies, and dietary guidelines.

Praxeologically, this makes sense. As debasement or monetary inflation pervades the price and production structure, price inflation occurs—changing the economic situation for human actors, benefitting some and disadvantaging others. Producers, especially the honest—who are also consumers, must consider price-costs of inputs for what they produce, and cannot simply “pass on costs to consumers”—are forced into a trilemma.

The honest producer, who recognizes he is getting less with the devalued money, can 1) sell at the same prices for devalued currency, be defrauded, and take a loss; or, 2) increase prices, possibly lose customers and market share, and open himself up to customer displeasure and even possible price control legislation. Tempting the honest and benefitting the dishonest, a third option presents itself—debase the product in response to the debased money but present it as the same quantity and quality as before at the same price. (We could make this a quadrilemma if we add shutting down production). In fact, the honest are disadvantaged—possibly even berated—should they remain honest, therefore, there is a tendency in which the honest are driven from the market. They either become dishonest or leave the market.

Price Inflation & Food Choices

From the consumer side, if we simply consider the most obvious consequence of monetary inflation—price inflation—it is not difficult to also see how this affects an economy’s food consumption. When food prices increase due to monetary inflation, consumers have a few options—purchase less, purchase the same amount and sacrifice elsewhere, seek cheaper substitutes, wait to purchase, seek external assistance, shift to home production, go into debt or draw from savings, nutritional compromise, etc.—but their food choices cannot remain unaffected.

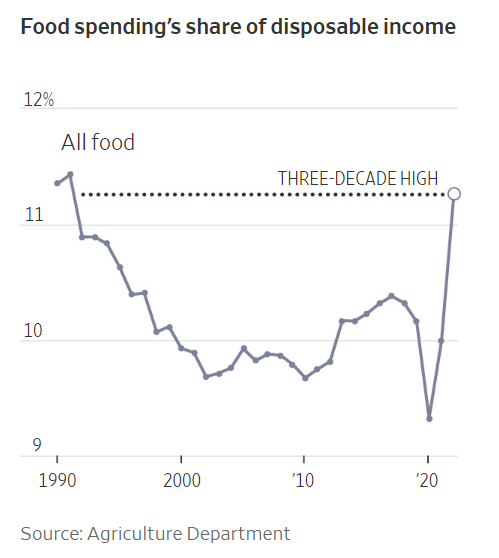

Recently (February 21, 2024), one article, titled “It’s Been 30 Years Since Food Ate Up This Much of Your Income,” provided the following graphic documenting percentages of consumer income dedicated to food:

Unsurprisingly, rising consumer prices, especially at the grocery store, were arguably a major issue in the 2024 presidential election. In this direct way, people experienced the consequences of inflationary monetary policy on their diet.

Ironically, even while rising food prices strain family budgets, some official inflation metrics—like the widely-cited Core CPI—exclude food altogether, masking the effect of inflation. Rothbard called this a trick of the “economic spin doctors.” He recounted how, in January 1990, the cost of living index reached over double-digit proportions—approaching the inflationary peaks of the 1970s—public concern was largely muted. Why was this the case?

...the economic spin doctors were quick to leap to their tasks. You see, if you take out the fastest rising price categories—food and energy—things don’t look so bad. Food went up by 1.8 percent in January—an annual rise of almost 22 percent; while energy prices went up by no less than 5.1 percent—an annual increase of over 61 percent.

If food is excluded, the reported inflation number is lower than what people experience in food purchases. Therefore, it is inescapable that inflation affects diet. Conversely, how could inflation not affect diet? What is measured does not change what people eat, but what people can afford will.

Layering irony upon irony, when the consequences of monetary inflation became manifest in price inflation during the 1970s, particularly in food, Richard Nixon appointed Earl L. Butz to serve as secretary of the US Department of Agriculture partially to address food price increases through central planning.

Increasing food prices—largely due to the unrestrained monetary inflation that followed 1971—were becoming a political problem. Attempting to bring down food prices via more inflation, subsidies, cronyism, and bureaucratic management, Butz told farmers, “Get big or get out.” Artificially low interest rates flooded farmers with capital to increase productivity, effectively squeezing out smaller farmers and consolidating remaining farmers. While this did result in lower food prices, it was not the outcome of a free market but of government-managed production and distortion. Saifedean Ammous, again, explains (pp. 113, 114),

As prices of highly nutritious foods rise, people are inevitably forced to replace them with cheaper alternatives. As the cheaper foods become a more prevalent part of the basket of goods [used in core CPI], the effect of inflation is understated….

By subsidizing the production of the cheapest foods and recommending them to Americans as the optimal components of their diet, the extent of price increases and currency debasement is less obvious.

By flooding the food system with cheap, subsidized calories, the government masks real inflation while shaping consumer behavior. Artificially-subsidized food—when included in the “basket of goods” used in the mostly meaningless Consumer Price Index (CPI)—appears to reduce price inflation. Americans, however, are effectively driven away from and toward food choices they otherwise would not have made because certain foods are taxed and others are subsidized.

“Price rises do not elicit equivalent increases in consumer spending; they bring about reductions in the quality of consumed goods” (p. 113). Consumers are driven to artificially cheaper, subsidized, and less nutritious food alternatives. Wealth seems to be increasing—and there have been historical wealth increases because of genuine production alongside artificial growth—but it is largely farcical. While obesity used to be seen as a signal of wealth, now it is arguably the opposite: “obesity is actually a sign of malnutrition.” Just as fiat inflation impoverishes while giving the impression of increased wealth, obesity seems to represent abundance when it is actually a form of malnutrition. In other words, “your wine has become water” (Isaiah 1:22).

Shrinkflation & Skimpflation

On the producer side, many have noticed—whether anecdotally or otherwise—the phenomenon known as “shrinkflation.” In explaining monetary theory and inflation to high school seniors, I asked for a student to produce a bag of chips and hold it up (there was never a class that didn’t have one). I would instruct the student to use two fingers to pinch near the top of the bag and run them down—showing all the air—until they finally hit the chips. This was one illustration of how inflation affects products, especially food. Some vigilant observers have chronicled examples.

Jeff Degner in his Inflation and the Family—where he traces the impacts of monetary inflation’s impact on marriage and the family—develops this point a bit further in a footnote (p. 81, n12),

There is evidence that the ancients also recognized a connection between debasement, inflation and food quality. The Jewish prophet Isaiah (1:22, King James Version) declared, “Thy silver is become dross, thy wine mixed with water.” If taken literally, the prophet seems to identify what modern economists have called “shrinkfation” or a lowering of the quality of food in response to a lowered quality of money that is associated with debasement and inflation along with declining health outcomes and life expectancy. Indeed, the US has not kept pace with the rest of the OECD nations with respect to life expectancy increases, and has even begun to decline in recent years, a situation that many blame on low quality food products. See Avenado and Kawachi (2014) for plausible food quality links along with other features of the inflation culture and their impact on mortality and morbidity outcomes in the US…

Shrinkflation is perhaps the simplest and most literal form of this process—smaller quantities are provided for the same or increased prices. Not only do prices tend to increase, but the monetary unit literally purchases less. The producers, in response to the monetary debasement and increased price inflation, find clever ways to reduce the product—presenting it as the same amount—lest they simply accept being defrauded.

In terms of food quality and nutrition, Degner, again, highlights a possible connection between monetary policy and reproductive health,

As for any connection between biological reality and expansionary money supplies, this might at first glance seem like a tenuous connection. However, it has recently been suggested that inflationary monetary policy degrades the quality of food and nutrition (Ammous 2021), which may in turn impact reproductive health. Indeed, diet, nutrition, and food security are among the factors that healthcare experts call the “social determinants of health.” These have been shown to impact fertility, maternal morbidity, and mortality, all of which suggest that the role of price increases in matters of diet, health, and live births should not be dismissed out of hand as irrelevant or trivial (Kozhimannil et al. 2019). (p. 81)

Intellectual Debasement and the Interventionist Paradigm

Many have noted the effects of food price inflation on health and well-being, especially amongst the most vulnerable. However, misunderstanding the causal chain between monetary policy and price inflation, and not understanding the causal consequences of decades of government interventions, the problem is usually misdiagnosed and the would-be solutions are counterproductive. Even recognizing the failure of past and current government interventions, many operate within a paradigm where the only answer is to call for more government intervention.

For example, in “How inflation is hurting the diets of low-income Americans” we read, “Despite government programs encouraging and subsidizing healthy foods, the problem is only growing.” The interventionist mindset will even recognize government failures—while “encouraging and subsidizing healthy foods,” they admit “the problem is only growing”—but will almost inevitably call for more intense government intervention to address the problem. The same article continues, “As much as these advocacy and subsidy programs help, the downward trend in healthy eating is pervasive. Inflation makes shopping for healthy food harder but not impossible. It’s about habits as much as price tags.” In other words, the government interventions help and the problem is worsening simultaneously.

Another study, “Food inflation and child undernutrition in low and middle income countries” argues, “This evidence provides a strong rationale for interventions to prevent food inflation and mitigate its impacts on vulnerable children and their mothers.” To be fair, the authors might mean healthcare “interventions” rather than government interventions, but it is rare to read any articles that do not call for an increasing role of the state.

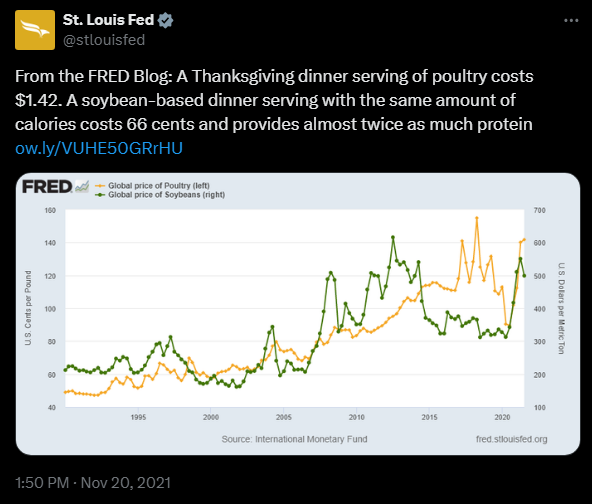

Sound economics is necessary to correctly diagnose the problem and to recognize and avoid false solutions based on misdiagnoses. And, if the reader is not yet convinced that the Fed—as a central banking institution—has any interest in intervening in your diet, see the following pre-Thanksgiving tweet from the St. Louis Fed (for which I am indebted to a previous Mises article):