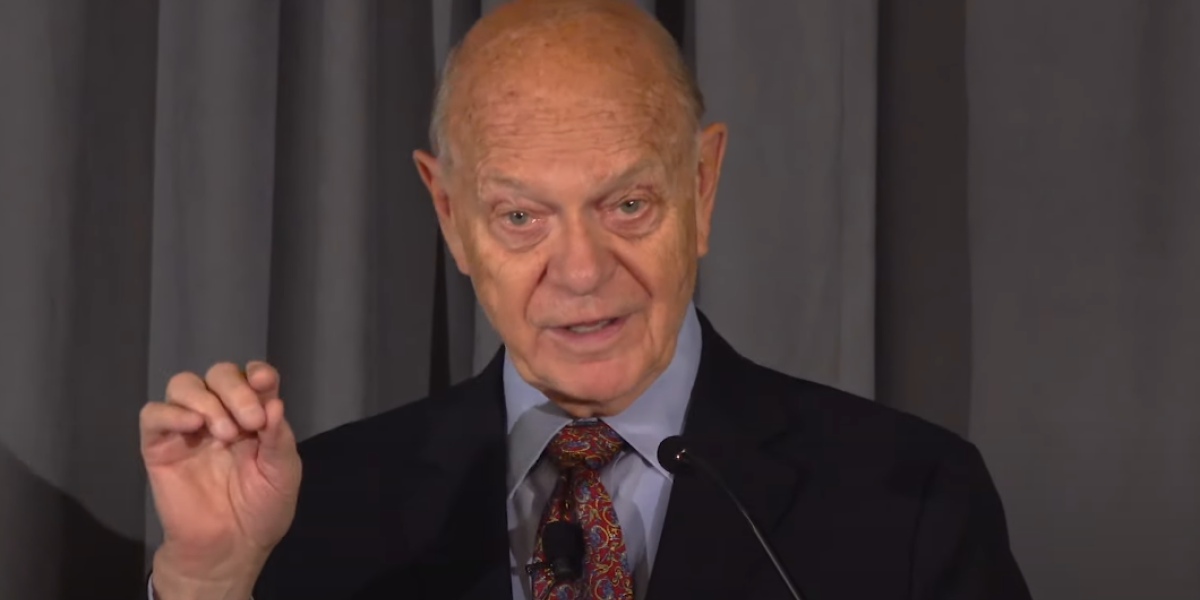

Testimony of Alex J. Pollock Senior Fellow, Mises Institute

To the Task Force on Monetary Policy, Treasury Market Resilience, and Economic Prosperity, Of the Committee on Financial Services, U.S. House of Representatives

Hearing on “Less Mandates. More Independence.”

September 17, 2025

How Congress Should Oversee the Federal Reserve’s Mandates

Mr. Chairman, Ranking Member Vargas, and Members of the Task Force, thank you for the opportunity to be here today. I am Alex Pollock, a senior fellow at the Mises Institute, and these are my personal views. As part of more than five decades of work in banking and on financial policy issues, I have studied the evolution of central banks and their role, banking systems, housing finance, cycles of booms and busts, risk and uncertainty in financial systems, and many other financial policy issues. I have previously served as the Principal Deputy Director of the Office of Financial Research of the U.S. Treasury Department, a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and president and CEO of the Federal Home Loan Bank of Chicago 1991-2004.

My View of Fed “Independence”

Although the Federal Reserve itself and its supporters constantly assert that the Fed is and should be “independent,” I believe this idea, if taken literally, must simply be rejected. No part of the government can be an independent power, let alone “autonomous,” as is sometimes said; none, including the Fed, can be immune from the Constitutional system of checks and balances fundamental to our republic.

In my view, the Fed in monetary affairs is “independent” in the limited sense of being independent of the Executive, but it is fully accountable to Congress, and indeed Congress has plenary power over it. As is often observed, this derives from the Money Power given solely to Congress under Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution. It also derives from the Taxing Power given solely to Congress by the same section, since the inflation created by the Fed is in fact a tax on the people.

A good historical statement of the Constitutional relationship was by a prominent Democratic Senator, Paul Douglas, who told Fed Chairman William McChesney Martin, “Mr. Martin, I have typed out this little sentence which is a quotation from you: ‘The Federal Reserve Board is an agency of the Congress.’ I will furnish you with Scotch tape and ask you to place it on you mirror where you can see it each morning.”

Like any good boss, the Congress should not meddle in too many details of its subordinate’s work, but it should be responsibly involved in the major policy issues and strategic directions. For example, should the United States commit itself to perpetual inflation and perpetual depreciation of its currency at some rate? I suggest that the Fed does not have the authority to regulate the value of money in this fashion, or to pick a particular rate of its constant depreciation, without approval from Congress.

On another occasion Chairman Martin clearly explained why the Fed must be independent of the Executive: the Treasury is the borrower and the Fed is the lender. You should not have the borrower be the boss of the lender (a dangerous monetary situation known technically as “fiscal dominance”).

Nonetheless, in reality, of course the Fed always exists in a web of Presidential power, policies, politics and influence. Historically, in times of major wars and economic crises, the Fed has always become the close partner and indeed the servant of the Treasury.

But in general, the accountability of the Fed runs to Congress and “More Independence” in the correct sense requires more substantive accountability to Congress. This should include oversight of the Fed’s own financial performance, since the Fed is running $240 billion in operating losses which continue, and its capital is deeply negative; these increase the federal deficit and the national debt, both key Congressional responsibilities. Imposing these losses and substantial risk on the government’s finances requires oversight, in addition to the many other issues of central banking.

Both the Federal Reserve Reform Act of 1977 and the Humphrey-Hawkins Act of 1978 were intended by Democratic Party majorities to make the Fed more accountable to Congress, though the reports of the Fed to Congress they require have perhaps not achieved the hoped-for result. I am sure Congress can further improve the Fed’s accountability.

How Many Mandates?

To think about “Less Mandates,” we should consider how many mandates the Fed actually has. I count eight, of which the Fed has displayed long term competence at only the first two. The eight are: provide an elastic currency, finance the government, promote stable prices, maximum employment, and moderate long-term interest rates, regulate for financial stability, make money for the government, and pay for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

Elastic currency. Of the greatest seniority and standing among the Fed’s mandates is that which stood first in the original Federal Reserve Act in 1913, which began: “An Act to provide for the establishment of Federal reserve banks, to furnish an elastic currency.” An “elastic currency” means to be able to expand the stock of money and credit to finance panics and financial crises. It turns out that the Fed is good at this, having for example energetically furnished elastic currency in the panics of 2008 and 2020 and the banking stress of 2023. After the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, the U.S. currency has become more elastic than the founders of the Fed could ever have imagined. In addition to financing panics, it now enables the Fed’s goal of perpetual inflation.

Finance the government. An even more basic mandate of every central bank, including the Fed, is to finance the government of which it is a part. This includes supporting the credit standing of the government’s debt. “The feature that sets sovereign debt apart from other forms of debt is the unlimited recourse to the central bank,” as one expert explained. This applies to U.S. Treasury and the Fed, as to all the others, historically and now, and the Fed is also good at this. The Fed first made its reputation by financing the government during the First World War and is today monetizing the Treasury’s debt while we discuss it, owning over $4 trillion in Treasury securities, of which $1.6 trillion have a remaining maturity of more than ten years. The interest rate risk created by these investments (along with mortgage investments) is the source of the Fed’s massive losses.

The triple mandate. The Federal Reserve Reform Act of 1977 added three, not two, goals for the Fed; here is the statutory provision: “to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates”-- a triple mandate, not a “dual” one. Is it possible for the Fed to achieve all three together? Perhaps not. In any case, the third has become a dead letter, very seldom even mentioned by the Fed. With this mandate in the law, the Fed has nonetheless presided over both very high and artificially low long-term rates for long periods. When next amending the Federal Reserve Act, Congress may wish to delete this third item.

Turning to the remaining two, it is essential to observe that the statute says “stable prices,” not “stable inflation,” something very different. The Fed has in all its communications turned “stable prices” into “price stability,” and then defined “price stability” as perpetual inflation at a 2% rate—clever rhetoric. But is that what “stable prices” means? Stable prices rather suggests to me a desired average inflation of zero or so over time.

When he was Fed Chairman, Alan Greenspan said he thought the correct inflation target was “Zero, properly measured.” (Of course we would want to measure properly.) This is a fundamentally different position from what the Fed often calls “low and stable inflation.” Stable inflation means average prices will always rise. Even if the rate of inflation goes down, prices will still be going up. At a “low” 2% inflation, average prices will quintuple in a lifetime of 80 years. If “low” is allowed to be 3% (it has just been reported as running now at 2.9%), average prices will increase to 10 times their start in that lifetime. You can see why the Fed had to wait for Greenspan to retire before unilaterally announcing, without Congressional approval, its 2% inflation forever doctrine.

The Humphrey-Hawkins Act of 1978 suggested zero percent as a long-term goal for inflation. This may indicate what the Congress that passed the act meant by “stable prices.”

I am of the view that the most important thing the Fed can do is to provide stable prices with sound money that the people can and do rely on. This is also its best contribution to maximum employment. As the great Paul Volcker wrote, “Trust in our currency is fundamental to good government and economic growth.”

Congress could usefully clarify that it does not believe that central management by the government or by the central bank is the path to maximum employment. Neither the Fed nor anybody else has or can have the knowledge of the future it would take to “manage the economy” or successfully operate a national price-fixing committee. Quoting Chairman Volcker again, “The old belief that a little inflation is a good thing for employment, preached long ago, lingers on even though…experience over decades suggests otherwise.”

The Fed’s efforts, no matter how sincere, share with all tries at government central planning the impossibility of the requisite knowledge, as intellectually demonstrated by Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek a century ago and confirmed by much sad experience, including the two house price bubbles the U.S. has already had in first quarter of the 21st century. As Fed Chairman Jerome Powell candidly and wittily said about the Fed, “We are navigating by the stars under cloudy skies.”

Regulate financial stability. The original Federal Reserve Act also contained the mandate, “to establish a more effective supervision of banking.” This grew over time to trying to regulate the stability of the banking and broader financial system. The Dodd-Frank Act made the Fed the special regulator of “Systemically Important Financial Institutions” or “SIFIs.”

Unfortunately, it turns out that the Fed itself is the greatest SIFI of them all, with the greatest power to create financial instability by its mistakes, which are inevitable when dealing with profound and constant uncertainty. As Senator Jim Bunning said to Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, “How can you regulate systemic risk when you are the systemic risk?” An excellent question! Good recent examples of this are how the Fed’s giant investments in mortgage-backed securities stoked unaffordable house prices, and how its even bigger investment in very long-term securities encouraged the build up of huge interest rate risk in the banking system, which among other things, took down Silicon Valley Bank, threatened widespread bank runs, and caused the government to declare an emergency systemic risk event.

Make money for the government. The Federal Reserve was designed in basic structure to make money for the government by funding with the monopoly of issuing currency, which by definition has no interest expense, and then investing in interest-bearing assets. This is an automatic money maker, so the Federal Reserve Act allowed a dividend to the private shareholders of the Federal Reserve Banks and a small retained earnings account, but most of the profits got sent to the Treasury as a contribution to the federal budget. The Fed subsequently made money for 100 years. Today the currency outstanding is more than $2.3 trillion; invested at a current 4%, this would yield $92 billion a year, which would easily cover the Fed’s total non-interest expenses of $10 billion, leaving a net profit of $82 billion or a return of 178% on the equity of $46 billion the Fed claims to have. A great business as designed! This is the profit of what we should call the “Issue Department” after the logic of the English Bank Charter Act of 1844, still in force for the purpose of the Bank of England’s accounting.

The other part of the Fed is the “Banking Department,” or what we might think of as the hyper-leveraged hedge fund operation. In total the Fed lost $78 billion in 2024 in addition to wiping out the Issue Department’s profit, so in round numbers its Banking Department lost $160 billion. This is a hit to the taxpayers and shows that in recent times the Fed has failed to carry out this mandate.

In its defense, the Fed often argues that it is not a profit maximizer. But nobody said it was. It is not supposed to make maximum profits, but it is designed to make profits, not losses.

Pay for the CFPB. Ther Dodd-Frank Act mandated that the Fed, out of its earnings, had to pay the expenses of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. This was a stratagem to block future Congresses from exercising the power of the purse. In my view, the Fed should never have been used at all in this fashion, but now there are simply no earnings to send when the Fed has lost $240 billion. In my view, paying for the CFPB is a Fed mandate that should be deleted.

Fed Accountability Actions Congress Can Take Now

Based on the preceding discussion, I respectfully offer the following six suggestions for things Congress could do now to better oversee and create more substantive accountability for the Federal Reserve.

1.Sound Money Mandate

I believe that Congress should add to the Federal Reserve Act the statement that the most fundamental responsibility of the Fed is to furnish a sound currency that the people can, should and do rely on, adding that trust in our currency is essential to good government and economic growth.

2. Required Approval of Inflation Targets

Congress should make it explicit that the Fed must have Congressional approval to commit the country to any long-term inflation target. It should announce an immediate review of the “2% inflation forever” target which the Fed unilaterally announced, to decide whether Congress will approve it or some other policy. This is consistent with the practice of other countries, where any inflation target has to be agreed upon between the government and the central bank.

The new policy will define what “stable prices” means in terms of direction for the Fed. It might be a range for inflation of between zero and 2%; or “less than 2%” like the central bank of Switzerland, which provides a high-quality currency; or a long-run average of zero with variations of perhaps -1% to 2%. In my judgment it should not be 2% inflation forever, but it might be. We will see what the outcome is of the open discussion of what kind of money America should have. The Fed should bring recommendations and alternatives to Congress for its consideration.

3. Oversight of the Fed’s Finances

Congress should carry out regular, formal oversight of the Fed’s financial statements and financial projections, including both the balance sheet and the income statement. The Fed’s assets are now over $6 trillion. The review should include the twelve individual Federal Reserve Banks, especially New York, which is as big as the other eleven combined. It is impossible to believe that the Fed intended to lose $240 billion both for itself and the taxpayers. The Congress should understand what is going on.

It should also understand the financial risks the Fed decided on its own to take, and be in agreement with significant risks before the Fed takes them going forward. These also create risks to the government’s finances.

I recommend that Congress require the Fed to practice standard accounting as defined for government entities by the Financial Accounting Standards Advisory Board, like the rest of the government. The Fed’s balance sheet hides its negative capital by pretending that its losses are an asset, while claiming that it has the power to make up its own accounting rules. This claim should be overruled, and the misleading accounting it has allowed corrected.

I also recommend that Congress require the Fed to report its financial statements divided into an Issue Department and a Banking Department. This would significantly enhance the clarity of what is really happening.

4. Exit Mortgage Investing

I believe Congress should direct the Fed to get out of the business of its market-distorting mortgage investments, which were supposed to be, and promised by Chairman Bernanke to be, temporary. Assuming that it cannot sell them now because of their huge market value losses, the Fed should let its $2.1 trillion MBS portfolio run off to the historically normal level of zero. Except temporarily in a crisis, as part of providing an emergency elastic currency, the Fed should never use its monopoly monetary power to subsidize any particular economic sector or interest. This is a foundational principle.

5. Recapitalizing the Fed

The Federal Reserve has an actual combined capital of negative $195 billion. The Federal Reserve Act from its beginning contemplated the possible need to buttress the Fed’s capital and provided means to do so. The first step would logically be to require the Fed, as provided for in the act, to exercise the call it already has on all its private bank shareholders for the half of their stock subscriptions not already paid in. That would raise new capital of $39 billion, a meaningful start. Further steps should be considered.

As part of recapitalization, it should be clarified that dividends to Federal Reserve stockholders may only be paid out of current profits or retained earnings. This is already provided for in the Federal Reserve Act, but Federal Reserve dividends are still being paid in the absence of any earnings, current or retained.

6. Subcommittees on the Federal Reserve

I think this Task Force is a great idea, but do respectfully suggest that Congress consider forming Federal Reserve Subcommittees in both the Senate Banking and the House Financial Services Committees. The massive economic and financial importance and influence of the Fed, nationally and globally, its role in systemic risk, and the difficulties of the questions involved, would seem to warrant this step. Accompanying it would be growth in the specific knowledge and expertise needed to effectively carry out the Constitutional Money Power of the Congress.

Thank you again for the opportunity to present these views.