Western and American culture can be said to have undergone a process of infantilization—reduction to a childish and immature state. The familiar maxim “hard times create strong men; strong men create good times; good times create weak men; weak men create hard times” has been applied quite a bit recently to American culture. This quote seems particularly apt regarding, not just economic ignorance, but economic immaturity. The hard-won, time- and labor-intensive wealth of the West is simply taken for granted and assumed to be normal.

Mises reminds us, “Every single performance in this ceaseless pursuit of wealth production is based upon the saving and the preparatory work of earlier generations.” This is easily forgotten as many are either born into or get used to the wealthy modern context, which was enabled by a long, painstaking wealth-building process. This process involved intense sacrifice, low time preference, forward thinking, production, exchange, labor, saving, division of labor, and capital investment.

Whether we realize it or not, we are the beneficiaries of the incalculable saving and preparatory work of previous generations. Economics helps us understand and appreciate human action, opportunity cost, scarcity, the role of time, production and consumption, saving, and many other key concepts. Without this knowledge, it is easier to become infantile and childish, assuming existing wealth as an automatic given. Economic infantilization even encourages arguments for policies which would destroy the foundations that made wealth possible.

It is easy for all of us to take certain things for granted because of unexamined presuppositions. For example, when we receive clean water immediately from the sink, we often pay no thought to the process that makes such a thing, not only possible, but normal. Further, we also often assume we know much more about a process than we do. Imagine going back in time over a century and explaining how electricity or Google really work. Arthur C. Clark said, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” In other words, even among the things that surround us every day, we would be at a loss to explain how they really work beyond a few steps so they might as well be “magic” to us.

Part of the genius of Leonard Read’s “I, Pencil” was that it traced back many of the elements of a completed pencil backward through the stages of the time-structure of production, showing us how little we really know about what we think we know about even the most simple items. A similar lesson comes from the man who made a sandwich almost totally from scratch, which took 6 months and $1,500. (It should be noted that he still utilized modern tools, a boat, a plane, a kitchen, without which the process would have been even longer and more expensive). There was also the man who attempted to build a toaster from scratch (which didn’t even work). Further, a recent Facebook reel described the adult realization—which many adults never realize—concerning just how much prior and current work is necessary to enable things we take for granted.

Thankfully, people do not have to fully understand the “magic” of the division of labor, trade, and the development of a capital structure to benefit. However, this happy ignorance may also lead people to inadvertently take certain conditions for granted as they suggest policies which would undermine what they unknowingly presuppose. Concerning economic ignorance, Rothbard said,

It is no crime to be ignorant of economics, which is, after all, a specialized discipline and one that most people consider to be a “dismal science.” But it is totally irresponsible to have a loud and vociferous opinion on economic subjects while remaining in this state of ignorance.

Economic Ignorance and Infantilization

Imagine some ungrateful young children who grow up in a fairly wealthy, middle-class home. One day—sick of their parents’ rules and strictures—they successfully kick their parents out of the house. Having watched their parents run the household, they assume it will be easy to do it themselves, in fact, they will do it better. Their immature assumption was that their parents simply had the unearned privilege of possessing and distributing resources and did so capriciously. However, they soon realize that—though they were accustomed to a house with food always in the refrigerator, electricity behind every switch and plug, WiFi, air conditioning and heat, running water, garbage collection, etc.—these things were not automatic and their parents did not just have the privileged position of distributing them. Their ignorance, immaturity, and ungratefulness led them to take their parents’ wealth for granted without understanding it. In this parable, the parents do not represent the state, rather they represent the underappreciated past and current production, saving, and investment that a modern economy cannot do without but which is all too easy to take for granted.

Largely for lack of economic understanding, among other reasons, many—enjoying the hard-won wealth of a modern, industrial economy—become infantile, even to the point of arguing for policies that would undermine the wealth they enjoy. Howard Zinn exemplifies this infantile mindset in his Marx in Soho: A Play on History,

Give people what they need: food, medicine, clean air, pure water, trees and grass, pleasant homes to live in, some hours of work, more hours of leisure. Don’t ask who deserves it. Every human being deserves it.

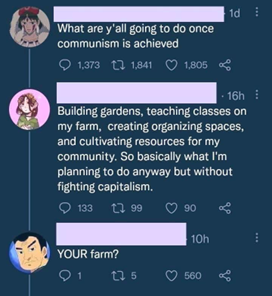

While much could be said about this vapid statement, probably the most central issue is the unjustified presupposition that all the scarce goods mentioned simply need to be distributed, not produced and exchanged. Zinn—and many like him—apparently share the childish outlook that these goods are abundant and, were nice people like him in charge, these goods would just be freely given to all since all deserve it. It totally overlooks what Rothbard called “the production-and-exchange process,” by which all legitimate economic progress is made. Further, the solution is simple and easy—just give people what they need. Hence, to the extent that people lack any of these scarce goods, it apparently represents an injustice. Scarcity and the disutility of labor—core assumptions of economics—are not regarded as constraints of reality, but contrived and imposed by mean people who never learned to share. As another fairly typical example, see this comment thread:

Mises versus Romanticism

In Socialism, Mises addressed the infantilization of culture in his discussion of romanticism (which I highly recommend). He believed that through romanticism, especially through literature and other media, prepared the groundwork for socialism. Mises makes two key statements that capture the infantilizing nature of romanticism: 1) “No romantic has perceived the grandeur of capitalist society.”; and, 2) “Romanticism is man’s revolt against reason, as well as against the condition under which nature has compelled him to live.”

Based on Mises’s insights, we see key overlapping themes of economic infantilization—lack of understanding and appreciation of what made capitalist society possible, a rejection of the constraints of logic and reality in favor of unconstrained imagination and feelings, and a resentment against the limitations imposed by reality. When economic ignorance, unchecked presuppositions, the fruit of capitalist wealth, democratic high time preference, and romanticism combine, one result is infantilization.

Economic Ignorance and Lack of Appreciation

Many overlook the fact that, “Civilization is a product of leisure and the peace of mind that only the division of labour can make possible.” This is one of the lessons taught by “I, Pencil.” The wealth that allows enough leisure and resources to pursue other objects—like complaining about free market capitalism—is ironically enabled by the production, exchange, saving, the division of labor, and capital investment. Taking all this for granted, many tend to ignorantly romanticize the past,

The romantic takes all the gifts of a social civilization for granted and desires, in addition, everything fine and beautiful that, as he thinks, distant times and countries had or have to offer. Surrounded by the comforts of European town life he longs to be an Indian rajah, bedouin, corsair, or troubadour. But he sees only that portion of these people’s lives which seems pleasant to him, never their lack of the things he obtains in such abundance.

Simultaneously, many enjoy the fruits of imperfect, hampered free markets, assuming the wealth generated as automatic because they are ignorant of the source, and argue—directly or indirectly—for policies of economic destructionism. Mises wrote,

They all reject the capitalist social order and combat private ownership in the means of production, without perhaps always being conscious of it. Between the lines they suggest an inspiring picture of a better state of affairs economically and socially. They are recruiting agents for Socialism and, since Socialism must destroy society, are at the same time paving the way for destructionism.

Rejection of Logic and Reality for Unconstrained Imagination

It is not just that the romanticist-socialist or socialist sympathizer is simply ignorant of economics and unappreciative of the wealth and the wealth-generation process that he takes for granted, but he rejects logic and reality for unconstrained imagination and feelings. Mises warned, “Where reason ceases to function the way to romanticism is open.” He further described the source of their economic and intellectual immaturity,

It is the inability to understand the difficult problems of social life which renders ethical socialists so unsophisticated and so certain that they are competent to solve social problems offhand…. In every man there is a deeprooted desire for freedom from social ties; this is combined with a longing for conditions which fully satisfy all imaginable wishes and needs.

Failing to appreciate the constraints of reality, such as scarcity and the disutility of labor, in favor of imagination and feelings, they mistake the ability to imagine solutions for solutions. This is also why such imagined solutions are typically vapid and childish. Without appreciating problems within the constraints of logic and reality, they cannot begin to approach real solutions. Mises speaks to the role of unconstrained imagination in this mindset,

The romantic is a daydreamer; he easily manages in imagination to disregard the laws of logic and of nature.

The romantic movement, which addresses itself above all to the imagination, is rich in words. The colourful splendour of its dreams cannot be surpassed.

This is why—even as we are constantly reminded that real communism has never happened—communism is supposedly viable “in theory.” In reality, socialism and communism have been demolished in theory as well as in practice. The reason why these theories do not work in practice is because they are bad theories. What should really be said is that communism and socialism work “in my unconstrained imagination” or unrealistic fantasy. The key mistake is to assume that because something can be imagined without difficulty that it must therefore be viable.

Imaginary constructions are key in economics, however, these have to be used carefully and remain limited to sound logic. If we consider human flight, for example—which was once thought impossible and certainly required imagination—it must be admitted that there is a categorical, qualitative difference between the constrained imagination that enabled human flight and the unconstrained imagination of a kid pretending to be Superman, especially if constraints like gravity are viewed as unjust social constructs. Therefore, Mises writes of the childishness of romanticists,

Here [in reality] one must plough and sow if one wishes to reap. The romantic does not choose to admit all this. Obstinate as a child, he refuses to recognize it. He mocks and jeers; he despises and loathes the bourgeois. (emphasis added)

Romantic Resentment of Reality

Lastly, the romanticist-socialist is not simply ignorant of economic reality, rejecting logic and reality in favor of unconstrained imagination, but he resents reality. This is evident when given conditions of logic, nature, and reality are interpreted, not as tragic constraints, but as moral injustices.

I once had a conversation with a former co-worker who told me about how little bears labor for survival and how much they sleep relative to humans. The contextual implication was that the requirements for human labor were both unnatural and unjust, not just facts of reality. Scarcity, the disutility of labor, and other constraints are resented as contrived and unjust.

All humans act to alleviate “felt uneasiness,” and wealth—achieved through production and exchange—mitigates scarcity. In order to achieve sustained economic progress, one must accept the constraints of reality and use his reason to act and manipulate the materials of reality. The alternative—made possible because others pursued the former course—is that of infantilization: resent logic and reality in favor of unconstrained imagination and falsely solve problems by wishing. Mises summarizes,

The thinking and rationally acting man tries to rid himself of the discomfort of unsatisfied wants by economic action and work; he produces in order to improve his position. The romantic is too weak – too neurasthenic – for work; he imagines the pleasures of success but he does nothing to achieve them. He does not remove the obstacles; he merely removes them in imagination. He has a grudge against reality because it is not like the dream world he has created. He hates work, economy, and reason.