[Order Michael Finch’s new book, A Time to Stand: HERE. Prof. Jason Hill calls it “an aesthetic and political tour de force.”]

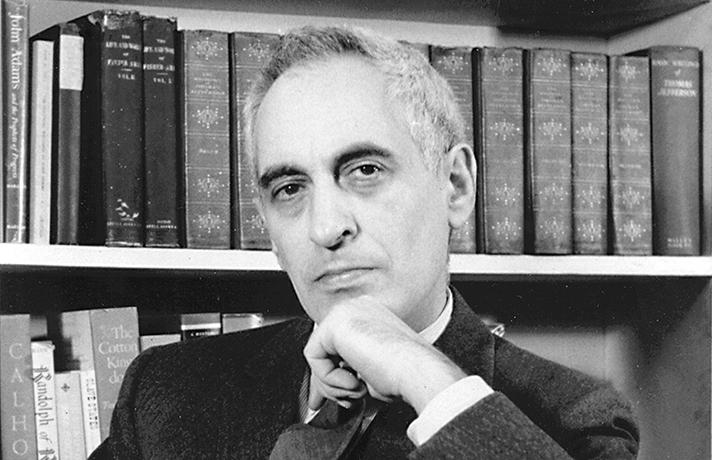

Ask the random conservative to name a modern architect of his political philosophy and names like Russell Kirk or William F. Buckley are likely to come to mind. Maybe George Will or Irving Kristol, Barry Goldwater or Ronald Reagan. It would take a perceptive student of conservatism to come up with the name of Frank S. Meyer.

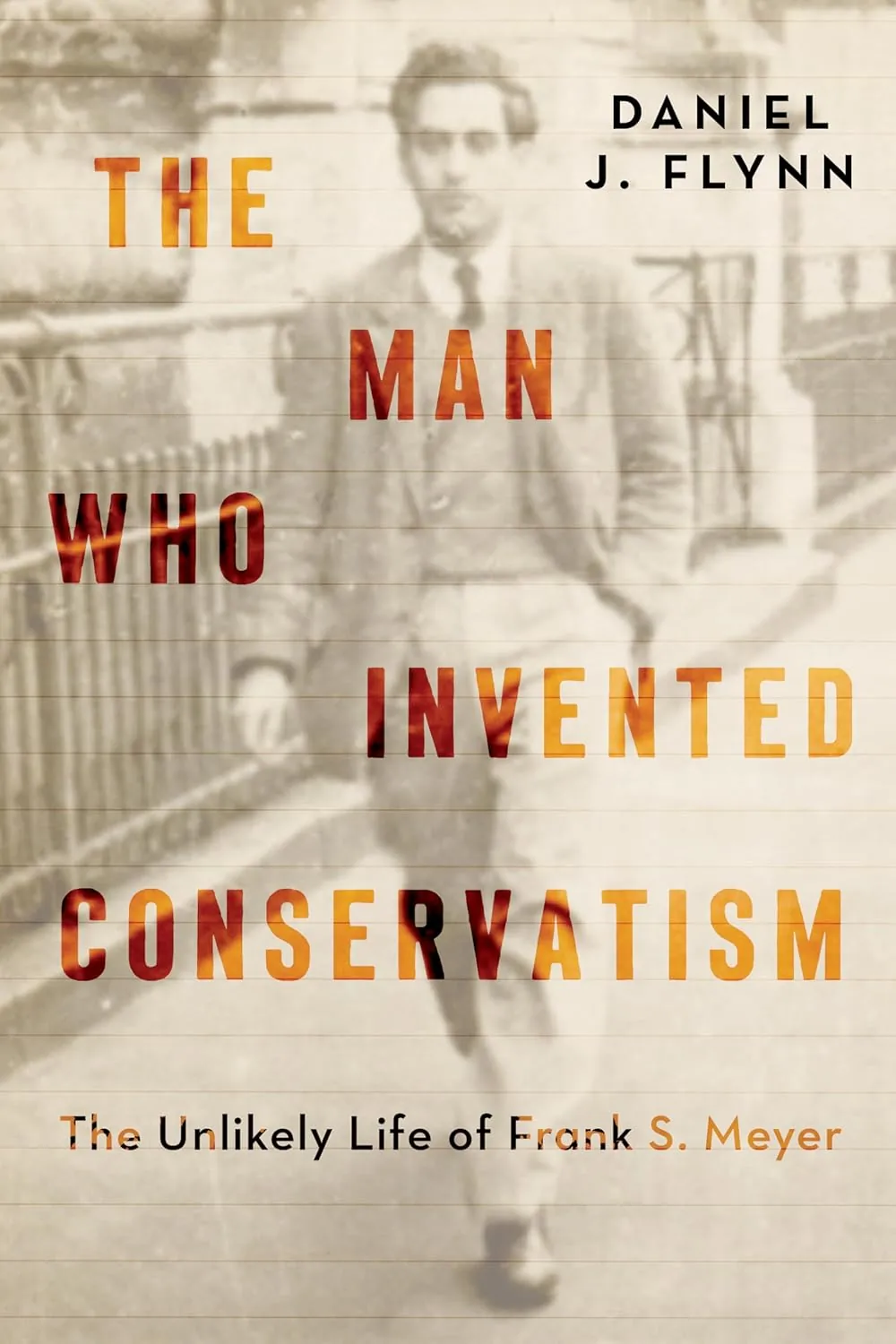

Daniel J. Flynn’s brand new book The Man Who Invented Conservatism: The Unlikely Life of Frank S. Meyer is a riveting, meticulously researched biography that breathes life into the extraordinary journey of Meyer, a man whose intellectual odyssey from fervent Communist to architect of modern American conservatism is as improbable as it is inspiring.

FrontPage Mag contributor Daniel Flynn is a senior editor of The American Spectator and a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution. He is the author of seven books including A Conservative History of the American Left; Cult City: Jim Jones, Harvey Milk, and 10 Days That Shook San Francisco (I interviewed him about that one for FrontPage Mag here); and Why the Left Hates America, which I’ve also read and recommend.

Flynn’s new biography is a compelling contribution to the historiography of American political thought. It not only chronicles Meyer’s dramatic transformation from far Left to conservatism (not unlike the political conversion of the Freedom Center’s late founder David Horowitz), but also situates him as a pivotal figure in shaping the conservative movement, influencing political giants like Reagan and Goldwater. Through a treasure trove of previously unpublished correspondence which Flynn discovered in an Altoona, Pennsylvania, warehouse – 663 boxes containing 250,000 personal papers – the author unveils a vibrant portrait of a man who interacted with a constellation of luminaries of his time, from C.S. Lewis and science fiction writer Theodore Sturgeon to conservative icons Kirk and Buckley.

Meyer was born in 1909 to a wealthy Jewish family in Newark, New Jersey. As a student at Oxford University in the early 1930s, he became a firebrand of the Communist movement, founding the October Club and serving on the board of the Communist Party of Great Britain. Flynn vividly recounts how Meyer’s activism made him a cause célèbre, with cries of “Free Frank Meyer!” echoing in London to prevent his deportation. This period of Meyer’s life, marked by his immersion in Marxist ideology and his role in mentoring early Communist leaders, is brought to life through Flynn’s discovery of documents, including letters and declassified British intelligence, which revealed Meyer’s clandestine romance with Sheila MacDonald, daughter of Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, and his service under a figure who later constructed the Berlin Wall.

Disillusioned by the Soviet Union’s realities and expelled from the University of Chicago’s graduate school in 1938 for his Communist activities, Meyer began questioning the collectivist dogma he once championed. Flynn illustrates how Meyer’s intellectual migration was not a sudden conversion but a gradual reckoning, influenced by his exposure to diverse thinkers and experiences.

One of the most fascinating episodes of Meyer’s colorful life involves an encounter with C.S. Lewis at Oxford, where the Christian apologist’s ideas planted seeds of doubt about atheism and collectivism. Though Meyer’s formal conversion to Catholicism came on his deathbed in 1972, Flynn argues that Lewis’ influence lingered, shaping Meyer’s eventual embrace of traditionalist values that would define his conservative philosophy.

By the 1950s, Meyer had fully rejected Communism, a transformation that led him to Bill Buckley and the founding of National Review in 1955. Meyer was the magazine’s “unofficial philosopher-in-residence,” where he developed “fusionism,” a synthesis of libertarianism and traditionalism that became the intellectual backbone of modern conservatism. Fusionism posited that individual liberty and traditional values were not at odds but complementary, a concept that resonated with emerging conservative leaders.

Flynn’s access to Meyer’s correspondence with Buckley, L. Brent Bozell, and others reveals the internal debates and rivalries that shaped National Review. Flynn captures the intensity of these editorial squabbles, making the reader feel as though he or she is eavesdropping on late-night phone calls from Meyer’s rural Woodstock home—described by National Review’s Priscilla Buckley as making Meyer “AT&T’s best customer.”

The Bulwark’s Joshua Tait complains that Flynn’s focus on National Review’s minutiae occasionally overwhelms the narrative. However, this is a strength for readers seeking a granular understanding of the conservativism’s formative years. Meyer’s influence extended beyond National Review to the broader conservative movement. Flynn details how Meyer’s ideas inspired Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign, particularly through Meyer’s seminal 1962 book In Defense of Freedom. Goldwater credited Meyer’s fusionism with providing a philosophical foundation for his campaign, which, despite its electoral defeat, laid the groundwork for the conservative resurgence. Similarly, Ronald Reagan, whom Meyer championed as early as 1966, embraced fusionism’s blend of anti-Communism, free-market economics, and traditional values. Flynn quotes Reagan’s 1981 CPAC speech, in which he praised Meyer for pulling himself “from the clutches of ‘The God That Failed’” and crafting “a vigorous new synthesis of traditional and libertarian thought—a synthesis that is today recognized by many as modern conservatism.” This acknowledgment underscores Meyer’s role as a visionary who foresaw the political realignment of America, predicting a coalition of traditional Republicans and Southern Democrats that culminated in Reagan’s 1980 landslide.

Beyond Lewis and Buckley, Meyer corresponded with author Joan Didion (who sent him Christmas cards), engaged with poets and pop stars in London, and mentored young conservatives, including his son Eugene, co-founder of the Federalist Society. These connections, unearthed through what Joshua Tait called Flynn’s “archival miracle,” paint Meyer as a magnetic figure whose intellectual curiosity transcended ideological boundaries. His rural home became a hub for conservative thought, where he cultivated talent and shaped institutions such as the American Conservative Union and Young Americans for Freedom.

The Man Who Invented Conservatism is more than a deeply-researched biography (Flynn amassed 110 pages of endnotes); it offers conservatives a reminder of their intellectual roots and the importance of principled debate. In 430 riveting pages, Flynn presents Meyer as a complex, flawed figure—a “sinner with many friends,” as he puts it—whose journey from Communist agitator to conservative kingmaker deserves far greater recognition. The Federalist’s Mollie Hemingway calls the book “a work of intellectual history of the highest order”; it is indeed an illuminating must-read for anyone seeking to understand the origins of American conservatism, anyone interested in the history of political thought, and anyone who is, as I was, largely ignorant of Frank S. Meyer’s seminal reach, which continues to resonate.

Follow Mark Tapson at Culture Warrior