[Want even more content from FPM? Sign up for FPM+ to unlock exclusive series, virtual town-halls with our authors, and more—now for just $3.99/month. Click here to sign up.]

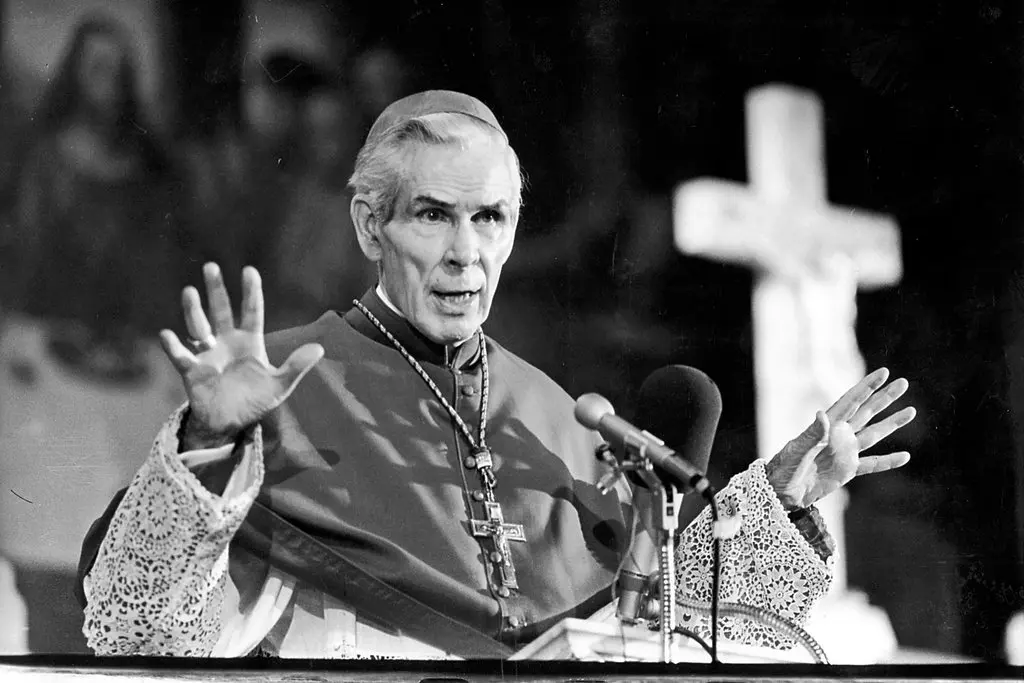

A few years ago, YouTube recommended to me a sixty-year-old, black-and-white video. The video featured a Catholic bishop, in full regalia: cape; zucchetto, or skullcap; wide, silk fascia, or waistband; and a large pectoral cross. The bishop paced in front of a minimalist set: a blackboard, a bookcase, a statue of Mary, a cross. The man gazed into the camera, and spoke. He used no notes. His speech was fluid and dynamic. And that’s all that happened, for the twenty-five-minute length of the broadcast.

I had initially hesitated to click on this link. Few people would feel compelled to devote time to such an old and unadorned video. I was curious, though. I vaguely remembered hearing about an old-time TV star named Bishop Fulton J. Sheen, how he had higher ratings than superstar comic Milton Berle. He was nominated for three Emmys, and won one, for “Most Outstanding Television Personality.” So I stopped what I was doing, and watched the Sheen video.

Sheen had crazy eyes. Intense, staring right into you. Those eyes announced that he was in touch with something beyond this earth. It’s a good thing he became a priest because people who burn as brightly as Sheen did, if they go down the wrong path, can do a lot of damage. Sheen poured himself into the camera. Watching this old video of a man who died in 1979 felt almost uncomfortably intimate.

I could instantly see how Sheen drew a reported thirty million viewers a week, seventy percent of whom were non-Catholic, who wrote him 25,000 letters a day. “You felt that one of the apostles was right there in front of you, speaking, and that if you missed the first twelve, well listen to Sheen, and he’ll have a similar impact on your life,” said one priest. An earthier assessment came from someone associated with his TV show. “If he came out in a barrel and read the telephone book, they’d love him.” Sheen was on the cover of TIME and LOOK and covered in Newsweek and LIFE magazines.

Defining charisma is like trying to capture lightning in a bottle. I can enumerate some of what captivated me in that first, startling exposure to Fulton J. Sheen. Sheen was striving to communicate to me why he was convinced that, as the title of his show insisted, “Life is worth living.” Is it? That’s a question I and millions of other humans struggle with daily. Sheen’s focused effort was a profound gesture of love for humanity. It’s vanishingly rare that I feel that someone”s speech is motivated by love. Even my doctors deliver the heaviest of diagnoses with apparent bored indifference.

Sheen wasn’t just about the heart. This was a man who had read widely and wasn’t afraid to let his audience know that. He invited his audience into his library, literal and metaphorical, to share his heady life of the mind. America, the Jesuit magazine, pronounced that, “The secret of Archbishop Sheen’s power was his combination of an educated and thinking head with a generous and feeling heart.”

And he laughed. He told jokes and he knew to wait for the audience to get them, to laugh, and then, a few beats later, to applaud. He was a consummate performer. I loved his insistence on wearing a full bishop’s regalia. No one wants peacocks to hide their visual riches. No one, not even Bela Lugosi, has ever worked a cape with the panache of Fulton J. Sheen.

A performer, a professional, yes, but something more. Those crazy eyes of his, his subtle body language, communicated that he was entirely alive to his encounter with you – his audience. He was willing to stand on the ledge, to risk vulnerability, humility, and the volatility of a living moment shared with another human being. I got the sense that, yes, he “had all the answers,” as one would expect of a bishop with a PhD and the first American to win the Cardinal Mercier Prize for International Philosophy. But I also got the sense that if I could turn back the clock and drop into Sheen’s office and present him with a dilemma he’d never encountered before, he’d toss aside his all-the-answers script and be willing, even if just momentarily, to be confused, scared, and overwhelmed with me.

Someone who met Sheen in person told TIME, “When one is with Sheen, one has the feeling of being important … He thinks that I am just as important to God as he. Maybe I am … This feeling is not dispelled by the knowledge that everyone else gets the same treatment.” As this person was leaving, another visitor arrived, and Sheen treated that new visitor with the same focused love he had expressed toward the previous visitor. “My time was up, but the impression remained. It just seems that everyone is important, everyone feels good.”

Sheen didn’t preach anything contrary to Catholic dogma, but he delivered his Catholic message in a package that anyone could hear. Biographer Cheryl C. D. Hughes writes, “Marvin Epstein, an anti-Catholic Jewish viewer, wondered, ‘How could he be making pronouncements which no person could reject, regardless of faith – because they simply made such maximal common sense?” Sheen answered this question. “Starting from with something that was common to the audience and to me, I would gradually proceed from the known to the unknown or to the moral and Christian philosophy. It was the same method our Lord used … This was the same method used by St. Paul.”

Sheen kept a daily “holy hour,” during which he meditated on the Blessed Sacrament. In one video, when America was confronting the Axis Powers, Sheen invites others to observe their own “holy hour.” “Think of the great spiritual transformation that there would be in America if every Jew, Protestant, and Catholic, according to the light of his conscience, prayed one continuous hour a day, for the president, for the Congress, and for victory.”

In one talk, from the 1960s, Sheen cites four men as “those whom the world regards as saints”: Gandhi, John F. Kennedy, Pope John XXIII, and Dag Hammarskjold. Gandhi was a Hindu who indulged in inappropriate behavior with young women. Hammarskjold was a Lutheran. He never married, and rivals spread rumors that he was gay. JFK was an imperfect man whose many affairs were an “open secret.” Sheen recognized that he was about to preach on the lives of imperfect men. He begins by addressing that, saying, whatever you think of these men, their lives do contain lessons for us all. He says that one feature unites them all: “Contemplata aliis tradere” or “hand on to others the fruits of contemplation.” This phrase is associated with Thomas Aquinas and the Dominican order. One must retreat from the world, meditate, and apprentice oneself to worthy traditions. But then one must go out into the world and share the fruits of one’s contemplation. All four of Sheen’s subjects for his talk demonstrated that value. Sheen didn’t just lecture on that idea, he lived it.

In 1988, Joseph Campbell, twenty years after Sheen’s program left TV, appeared in a hugely popular and influential PBS series, The Power of Myth. Campbell had been raised Catholic but left the Church and developed his own non-scholarly, quasi-religious “monomyth.” Campbell’s monomyth resembles the Aquinas quote. George Lucas, Star Wars’ creator, was influenced by Campbell’s monomyth and used it in crafting his saga. The seed of Star Wars, and Campbell’s monomyth, can be found in Sheen’s humble lecture, in front of a blackboard, and Thomas Aquinas’ thirteenth-century Latin phrase, “Contemplata aliis tradere.”

Watching Sheen on YouTube, I realized that if more priests were like him, I’d never miss mass. But I’d have to arrive early. When Sheen was a young priest, he served St. Patrick’s, a poor, immigrant parish in Peoria, Illinois. “His sermons were so popular that people had to come an hour early to get seats; he drew large crowds from other parishes.”

I did not fall in love with Sheen because I agree with everything he said. I do not. Sheen told jokes about women being vain chatterboxes. Those kinds of jokes were popular decades ago. I’m confident that if Sheen were among us today, he wouldn’t tell jokes like that. And after such a joke, he made it a point to uplift women with a subsequent compliment, and to make sure that the fellows in the audience had a chance to laugh at masculine foibles. Sheen preached on the value of suffering and pain. I’m allergic to those sermons; I’ve witnessed suffering erode human beings the way that polluted rain erodes marble statues.

Devout Catholics, inadvertently, make enemies on the left and on the right. Catholics who follow the “seamless garment ethic” oppose abortion and euthanasia – a stance favored by conservatives – and also oppose the death penalty – a stance favored by the left. Sheen criticized Communism during World War II, and that was controversial, since the USSR was a putative “ally.” Sheen is said to be the first American bishop to publicly oppose American involvement in the Vietnam War. Many on the right disputed that position. He supported the Church’s opposition to birth control, and he also supported the Church’s opposition to women priests – conservatives approve. Sheen was a redistributionist, giving ten million dollars of his own earnings to poor people in the US and overseas. That’s about one hundred million in today’s dollars. In the 1940s, before the Civil Rights era, Sheen championed black people’s rights. He donated large sums, for example, to the first hospital for black mothers in Mobile, Alabama, and he traveled to the South, met average black people, and left a lasting impression; see here.

So, no, I did not fall in love with the Sheen of YouTube videos because he was presenting arguments with which I always agreed. I loved him because his love and his skill at presentation knocked my socks off. But there’s more.

I grew up in a lost world that many modern-day Catholics wish they could will back into being. My neighborhood felt like one, big, extended family. People were Catholic, or, they were the other identity – “not Catholic.” There were so many of us, and we were so much a part of each others’ lives, that not being Catholic was itself a thing. Even the Catholics who didn’t send their kids to Catholic school were a tad exotic and suspect.

There were fifty-three kids in my first grade class in an eight-room Catholic grammar school. Fifty-three kids, one nun, one blackboard, no tutors, no aides, nothing electronic. Discipline was every bit as draconian as you’ve heard. Priests were remote and placed on a pedestal. Families had a mom and a dad. Parents were greatest generation; kids were baby boomers. Most of us descended from immigrants from Catholic countries like Italy, Ireland, or Poland. Before the school day began, we attended daily mass; a white lace mantilla draped over the heads of the girls; boys wore ties. We heard the church bells at six pm, and wherever we were, the Angelus came to us: “The angel of the lord declared unto Mary.”

Catholicism’s place in American culture was different back then. We were part of the culture. Jesuit priest Robert Drinan was a congressman. Father Andrew Greeley penned bestsellers with provocative titles like The Cardinal Sins. Hollywood made movies featuring religious themes. There were blockbusters, like The Ten Commandments and Catholic director John Huston’s The Bible. There were smaller ones, like Alfred Hitchcock’s I Confess, Huston’s Heaven Knows Mr. Allison, and Lilies of the Field starring a young Sidney Poitier. There were teen comedies, like The Trouble with Angels, starring Rosalind Russell as a nun dealing with rebellious girls in 1966. Angels was so popular it spawned a sequel in 1968. Fred Zinnemann’s The Nun’s Story was a serious work of art and one of the best American films devoted exclusively to one woman’s life. It received eight Academy Award nominations. Catholic identity was an accepted part of many films, for example The Sound of Music. Television featured a flying nun.

Influential filmmakers Alfred Hitchcock, John Ford, Frank Capra and Frank Borzage might not make overt reference to their Catholicism in their films, but film scholars see Catholicism’s influence in their filmographies. Quoting Peter Ackroyd’s 2015 biography, a Guardian reviewer wrote that Hitchcock’s “Catholic education gave him a sense of ‘mystery and miracle.’ What, after all, is ‘suspense,’ but a riff on the Catholic sense of awe at the unknown forces of the universe? Hitchcock’s religious sensibility informed films such as Vertigo, which, to Ackroyd, is ‘a reverie and a lament, a threnody and a hymn.'” Vertigo ends with a nun ringing a church bell and asking God for mercy.

Frank Capra came from a poor immigrant background. Even so, he was merely a “Christmas Catholic.” After his initial success, he had a breakdown. Suicide became a theme in his films and in his inner thoughts. An anonymous advisor said to Capra, “The talents you have, Mr. Capra, are not your own, not self-acquired. God gave you those talents; they are His gifts to you, to use for His purpose. And when you don’t use the gifts God blessed you with – you are an offense to God – and to humanity.” This encounter changed Capra’s life, and his filmmaking.

Scholars see Catholic concepts of ritual and community throughout the opus of one of America’s greatest filmmakers, John Ford. The final scene of The Searchers, where John Wayne stands alone, framed in a doorway he cannot enter, speaks of Catholic ideas, scholars say. There have been homages – or outright copies – of that scene in Breaking Bad, Star Wars, Taxi Driver, and Avengers; Age of Ultron.

One of the most remarkable expressions of the capaciousness of the Catholicism I grew up with occurs in a lighthearted romantic comedy made twice by Leo McCarey, first as the 1939 Love Affair and then as the 1957 An Affair to Remember. A gigolo, played first by Charles Boyer and then by Cary Grant, is carrying on a shipboard romance with a kept woman, played first by Irene Dunne and then by Deborah Kerr. The lovers, on a shore excursion, visit a chapel. The chapel changes them, and they are never the same. Sexy flirtation is no longer appealing. They want something else – deep, committed love. Life intervenes and challenges them both. She is hit by a car. Out of self-sacrifice, she breaks things off, without telling her lover that she is a cripple. He discovers her fate, and commits himself to her, in spite of her handicap. Again, this is a romantic comedy about a gigolo and a kept woman, written and directed by an imperfect Catholic who drank too much. And it couldn’t be more Catholic.

There was a worldwide pop music hit in 1963, “Dominique,” sung by a nun, about Saint Dominic. Other pop songs, like “Crystal Blue Persuasion,” “Jesus is Just All Right with Me,” “Spirit in the Sky,” “Morning Has Broken,” and “Put Your Hand in the Hand” voiced Christian themes.

Morris West became a bestselling author with several novels, like The Shoes of the Fisherman, that treated Catholic themes. Bestselling author Taylor Caldwell published dozens of popular novels. Great Lion of God was about St. Paul; Dear and Glorious Physician was about Luke. These books were sold in supermarkets and read on beaches and in airports. They weren’t targeted at “the faith market.” They were targeted at anyone who liked a rollicking good read.

That world is gone. Its absence is demonstrated is a 2025 romcom, Bridget Jones: Mad about the Boy, the fourth film in a popular franchise. Bridget had previously married the perfect man, Colin Firth as Mark Darcy. The series killed Darcy off. Bridget is now a single mother to Darcy’s two young kids. Their science teacher insists that there is no such thing as an afterlife. This makes Bridget angry and her kids sad. The film’s cast includes a mutant CGI owl. This white owl is a cross between a barn owl, a snowy owl, and a great horned owl, thus defying taxonomy, geographic distribution, and aesthetics. This mutant sits outside the kids’ window at night. The owl is meant to symbolize either Darcy watching over his family, or his family’s unresolved grief. The science teacher relents and tells the kids that their father is “everywhere” because energy can never be created or destroyed. The film’s director, Michael Morris, tries to explain the film’s conception of death. It’s about “keeping your heart open in both directions.” Helen Fielding, author of the book on which the film is based, said that her approach is “don’t get too #deathy … You don’t have to sit around feeling sorry for your loss.” There’s no coherence or depth to the film’s conception of death. Moderns rejected the wisdom of the Judeo-Christian tradition and replaced it with a mutant owl.

The Catholic world I grew up in, that is the Catholicism that reached the wider culture, including in the person of Fulton J. Sheen, was capacious. Yes, in my small town, divorce was rare and shocking. But a couple everyone knew to include one person who had been previously married to someone else, and then divorced, attended our church and sent a very popular daughter to our Catholic school. We all knew what virtuous behavior entailed, and domestic violence, alcoholism, and gambling were rampant. The folding chairs in the church basement, as well as the pews upstairs, were also full, during Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. You could find us all at mass. Even the juvenile delinquents attended, the pretty tough boys with their practiced sneers arrived too late to get a seat and stood in back; the girls in skirts way too short ignored their elders’ censorious glares and received communion along with old ladies all in black. Mass had room for us all, and we all wanted to be there. We got something from it. We were all sinners, just like the folks Jesus was accused of consorting with. See Luke 7:34.

In the wider culture, there was interdigitation between the sacred and the profane. Father Greeley’s novels included sex scenes. He had “the dirtiest mind ever ordained” according to the London Times. Taylor Caldwell was divorced twice. One of her husbands was a former Trappist monk. She tinkered with the idea that her historical novels were such rich reads because she had lived many past lives. Reincarnation is contrary to Catholic doctrine. Caldwell self-identified as a “Catholic-atheist” “because the tragedies in life have overwhelmed me.”

Jeanne-Paule Marie Deckers, the nun who sang “Dominique,” was a lesbian. She had a very rocky life, and she and her partner committed suicide. In their suicide note, they specified that they were still believing Catholics, and they wanted a funeral in accordance with the rites of the church and burial in consecrated ground. This is remarkable, because the Catholic Church long condemned suicide as a mortal sin, and until a change in canon law in 1983, suicides were not to be buried in consecrated ground. In spite of this, Deckers’ final request was granted, and she did receive a church funeral and burial in a Catholic cemetery.

Kathryn Hulme is the Catholic author who wrote the book on which the film The Nun’s Story was based. Her inspiration was Marie Louise Habets, a Belgian nun who asked to leave the convent at least partly because, living under Nazi occupation, she developed a hatred for Germans so intense it caused her to violate her commitment to charity. She left the convent and joined the anti-Nazi resistance. Hulme met Habets when both were working with war refugees in 1945. Both Catholic, they lived together for the next forty years, till Hulme died.

The 1965 film, The Agony and the Ecstasy, dramatizes Michelangelo’s creation of the Sistine Chapel ceiling. In one scene, Rex Harrison’s Pope Julius II, a very worldly warrior, dons a papal robe over a full suit of armor after winning a battle. The film is based on a novel by the Jewish Irving Stone. Michelangelo, a superstar of the Italian Renaissance, was a devout Catholic. He created the incomparable Pieta and David. To this day, five hundred years later, cardinals gather to select the next pope in the Sistine Chapel, under Michelangelo’s artworks. Michelangelo was – very probably – gay.

The other day I met a man who identified himself as having a lot of money, and, through that money, a lot of influence in Catholic circles. He told me that he devotes his donations to efforts to purge Catholicism of anyone who isn’t one hundred percent obedient to every jot and tittle of Vatican teaching. He wants, of course, to make sure that the church is cleansed of feminists and gay people and folks who are too much part of “the world.” He acknowledges that his proposed purge will leave Catholicism a fraction of the size it is now. This purged church, he insists, will somehow be stronger and better able to attract new converts. This man is not alone. There are many “trad Catholics.”

The number of their fellow Catholics whom they wish to remove from church rolls is high. One poll says that 99% of Catholics have used birth control. Most American Catholics want women priests, women deacons, and married priests. Most want the Church to bless same-sex couples. Most American Catholics believe that atheists can go to Heaven. This is a significant departure from the Church’s “Extra Ecclesiam nulla salus” stance. “There is no salvation apart from Christ and his One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church,” insists Catholic Answers. “This is an infallible teaching and not up for debate among Catholics.” In short, you sin merely by questioning this teaching. Well, opinion polls suggest that at least half of Catholics question or outright reject the dogma of papal infallibility. Finally, most American Catholics want the Church to be more inclusive.

The Catholic Church’s place used to be recognized in popular culture. A bishop used to be a popular TV star. That bishop, even while recognizing the gifts of non-Catholics like Gandhi and Hammarskjold, even while encouraging Jews and Protestants to pray ” according to the light of his conscience” brought the best of Catholicism to tens of millions of viewers, most of them not Catholic, who were deeply touched by his offerings.

In recent years, two forces have marginalized Catholicism. One is an anti-Catholic hatred. Catholicism is only corrupt and murderously intolerant and oppressive: Bill Maher and Christopher Hitchens exemplify this attitude. The other force marginalizing Catholicism are Catholics who want anything described as Catholic to be pure. Any such product, these purists insist, must strictly adhere to every Vatican dictate. These purists might kick Michelangelo,Taylor Caldwell, and the majority of their fellow Catholics out of the Church. Believe it or not, these purists include those who assess Pope John XXIII, Pope John Paul II, and yes even Fulton J. Sheen, as not really Catholic.

As Catholic educator John M. Dejak put it, “jihadi-traditionalist types seek an absolute spotless reality, a utopia that has never existed in the Church’s life throughout all the centuries. I suspect that they sometimes forget that we live in a vale of tears and imagine – somehow – that there was a time when Catholic discipline and belief was uniform with such military precision that the peasant and the prince never broke a fast, fell asleep at Mass, or slept with his neighbor.”

Why should anyone who isn’t Catholic care about Fulton J. Sheen, about Catholicism’s role in popular culture, or about what contemporary American Catholics think? Here’s why. The Catholic Church is one of the essential foundations of Western Civilization. Look at the history of the university, education, law, the hospital, public charity, human rights, marriage, just war theory, the development of the scientific method, and you find the Catholic Church. I agree with Tom Holland’s argument in this book, Dominion, that, overall, Catholicism has had a more positive than negative impact on culture. I agree with the new school of self-identified “Christian atheists” who recognize Christianity’s positive impact on Western Civilization, and who worry about what will happen to society as the numbers of believers declines.

No, not every influence that Catholicism exercised was positive. In the fifteenth century, Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer wrote Malleus Maleficarum, The Hammer of Witches. His book gave support to the witch craze. In the twentieth century, American priest Father Charles Coughlin commanded an estimated audience of thirty million radio listeners. Father Coughlin broadcast antisemitic material.

One gift of Christianity, a gift it has bequeathed to the West, is self-examination, confession, and self-correction. Church authorities condemned Malleus Maleficarum. Librarian Barbara Bieck explains, “Theologians of the Inquisition at the Faculty of Cologne condemned Malleus, stating that the book was inconsistent with Catholic doctrines on demonology and that it recommended unethical and illegal procedures.” Priests Friedrich Spee and Alonso de Salazar Frias significantly protected accused witches. Coughlin was eventually suppressed by Archbishop Edward Mooney, who, under the orders of the Vatican, told Coughlin to stop. The American government also suppressed Coughlin.

A better man replaced Coughlin as America’s most popular media clergyman. As Coughlin’s career was ending, in 1941, Fulton J. Sheen announced, “The persecution of the Jews is not the concern of the Jews alone, but is also a Christian concern … To be anti-Semitic is also to be anti-Christian. We must look upon the persecution of Jews and Christians today not as a separate, unrelated cause, but involving one another in some way because both are related to God.” B’nai B’right honored Sheen in 1939. The Federation of Jewish Philanthropies of New York presented Sheen with a “Gold Achievement Award” in 1954. When too many isolationists argued against U.S. involvement in World War II, insisting that “the Jews” were “dragging America into war,” Sheen passionately argued for American military involvement.

On November 30, 2024, Ignatius Press published Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen: Convert Maker by Cheryl C. D. Hughes. The book is 310 pages long, inclusive of footnotes, a bibliography, and an index. As the title suggests, the book’s primary focus is on Sheen’s work converting non-Catholics to Catholicism.

Convert Maker offers quick sketches of Sheen’s celebrity converts. I appreciated learning about those converts. For this reader, though, the book spends too much time advancing the Catholic Church as the only route not just to salvation, but just to human satisfaction. I see Sheen as the personification of an era when Catholics could be Catholic but still be part of popular culture, and a bishop could be beloved not just by Catholics, but also by Jews and Protestants. And Sheen’s converts were as motley a crew as those in the church pews of my childhood. At least one of his converts was gay, and others were divorced or in otherwise unconventional relationships. I’m afraid that Hughes’ passages pushing so hard at advancing Catholicism will alienate readers.

Convert Maker offers a short biography of Sheen. Sheen was born to Irish-American parents in El Paso, Illinois in 1895. He suffered a bout of tuberculosis and had lifelong lung and stomach trouble. A family friend said of the young Sheen, that he “will never be worth a damn. He always has his nose in a book.” He studied in Europe and won a prestigious prize. At thirty, he published God and Intelligence. Commonweal called the book “one of the most important contributions to philosophy which has appeared in the present century.” He was subsequently assigned to a poor, immigrant parish in Peoria. His superiors did this to make sure that the recognition of his brilliance had not rendered him proud. After eight months, he was sent to Catholic University. He began there in 1926 and remained for the next twenty-five years. In 1928, the Paulist Fathers broadcast Sheen’s sermons; his radio career had begun. In 1930, Sheen began his radio show, The Catholic Hour, which ran till 1950. As the reader can see, Sheen accomplished as much as might be expected from two or three men. He ate abstemiously and tended to weigh about 130 pounds. Hughes says he worked nineteen-hour days, and published over seventy books.

Sheen read Communist material and became “the best versed opponent of Communism in the United States.” The first celebrity convert Hughes covers is Louis Budenz, editor of The Daily Worker. Sheen and Budenz met for dinner. Sheen opened with “Let us now talk of the Blessed Virgin!” Sheen referred to Fatima, site of the Miracle of the Sun. “With an overwhelming vividness,” Budenz writes, “I was conscious of the senselessness and sinfulness of my life” as well as “the peace that flows from Mary.” Budenz left the Party, became an anti-Communist, and a devout Catholic.

Journalist Heywood Broun was “a large man, overweight, slovenly in his dress, a heavy drinker, and twice married.” A leftist, John Reed was his friend. He became convinced that Catholicism was more radical and more helpful to humanity than his politics. He studied with Fulton Sheen and converted. Afterward, Broun felt

“great peace of soul and a feeling of being home at last … much of liberalism was extremely illiberal … I discovered that freedom for [his liberal friends] means thinking as they did … it has dawned upon me that the basis of unity in radicalism is not love, but hate. Many radicals love their cause much less than they hate those who oppose it … I have also discovered that no social philosophy is quite as revolutionary as that of the Church.”

Ada Beatrice Queen Victoria Louise Virginia Smith was popularly known as “Bricktop.” She was a performer and nightclub owner. She was born in 1894 to a mother who had been enslaved. She was called “Bricktop” because of her red hair, inherited from her Irish, slave-owning grandfather. Bricktop’s audiences in Paris included F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, and John Steinbeck. Cole Porter was a close friend. Bricktop had affairs with both men and women, including Josephine Baker.

In 1939, Bricktop returned to America, and began listening to The Catholic Hour. Though Sheen never instructed her, his radio show converted her. She was baptized in 1943. She said of her conversion,

“I was finding rewards in just living … that I had never known before. My religion was making life happy for me again … I like the mystery of the Catholic Church … I found richness in the solitude of going to church, and the stresses of everyday life just didn’t seem as important any more … I became more aware of how necessary it was for those who had to help those who hadn’t, and in Rome I became involved in charity work.”

Bricktop’s nightclub patrons donated to her work with Rome’s postwar orphans. She became known as the “Holy Hustler.” Sheen heard about Bricktop’s charitable work for the Church, and they met in Rome. Years later, when she was down on her luck, they met again. Sheen asked her what she needed. “Five hundred, five thousand? What?” She accepted $500. Years later, back on her feet, she visited Sheen and paid him back. “It was the first time in his long lending career that anyone had repaid him.” Of Bricktop, Sheen said, “My child in Christ, Bricktop, proves every walk of life can be spiritualized.”

Clare Boothe Luce was a journalist, playwright, congresswoman, and ambassador. A woman whose ex-husband Luce would marry described Luce as having “the face of an angel and the morals of a prostitute.” Luce’s mother made her way through life by attaching herself to a series of men. Luce followed suit, marrying two men of wealth and power, and forming a friendship with Bernard Baruch, who was thirty-three years her senior, and also married. On a congressional tour of Europe, Luce witnessed GIs kneeling for a Catholic mass in a snowy field. Luce’s daughter had recently died in a car accident. Luce was suicidal. When meeting Sheen, Luce demanded to know why her daughter died. “Maybe your daughter is buying your faith with her life,” he replied. She wanted to convert, but she was a divorced woman living with a divorced man. Cardinal Spellman said “To hell with public opinion.” Actress Loretta Young, Luce’s friend, would say that after Luce’s conversion, “She remained strong, but in a positive way. I couldn’t believe she was the same woman.”

Fritz Kreisler was an Austrian violinist and composer. Of Jewish descent, he moved to the US in 1939. Sheen knocked on Kreisler’s door by chance, and offered instruction in Catholicism. Kreisler agreed. His wife Harriet converted as well. She had divorced her first husband. Even so, the Church accepted the Kreislers. Fritz Kreisler would compose the theme for Sheen’s TV show. When eulogizing Kreisler, Sheen remembered that he and Kreisler would pray the Lord’s Prayer together in Hebrew.

The Vassar-educated NKVD spymaster Elizabeth Bentley was an American Communist who became disillusioned with the Party. She left the Party and began to speak against it. Louis Budenz introduced Bentley to Sheen. Three years after leaving the party, Bentley was baptized. Hughes dismisses Bentley’s conversion to Catholicism. “One suspects that Elizabeth’s conversion to Catholicism was convenient and part of her attempt to remake herself for the public.” Bentley’s life was chaotic and unhappy. Sheen tried to help, getting Bentley a teaching job. Bentley sabotaged herself on the Catholic campus by drinking too much and “cohabiting with a man not her husband.” “By the end of 1952, she was contemplating suicide. Her newfound Catholic faith was not giving her peace of mind – neither were the liquor bottles piling up in her wastebaskets … Elizabeth added one more ex to her résumé and abandoned the Catholic Church.” Hughes is uncharitable in her comments about Bentley. From this distance, Bentley seems to have had psychological problems, perhaps borderline personality disorder.

Bella Dodd was another prominent American Communist who left the Party and who was mentored by Sheen. She testified to Congress, “I had regarded the Communist Party as a poor man’s party and thought the presence of certain men of wealth was accidental … I saw this was only a facade placed there by the movement to create the illusion of the poor man’s party; it was in reality a device to control the ‘common man’ they so raucously championed.” Dodd attended mass. “As I stood there” she said, “about me were the masses I had sought through the years, the people I loved and wanted to serve. Here was what I sought so vainly in the Communist Party, the true brotherhood of man. Here were men and women of all races and ages and social conditions cemented by their love of God.”

Cardinal Francis Spellman was Sheen’s superior. In 1984, John Cooney released a biography of Spellman that depicted Spellman as a major power broker and that also suggested that Spellman was an active homosexual. Cooney says he concluded this after researching Spellman’s diary, FBI documents, and interviewing priests and politicians who knew Spellman. See here. In any case, Spellman was a flawed man. Spellman tried to “con Sheen out of money” and he also “lied to the pope” about this scheme. When Sheen resisted, Hughes reports that Spellman hired “investigators to look into Sheen’s private affairs in hopes of turning up something incriminating.” In the end, Spellman “saw to it that Bishop Sheen was pulled off the television airwaves.” Spellman wasn’t hurting only Sheen. He was also hurting the Church, and especially Third World missions, as Sheen was such a powerful fundraiser. Spellman sent Sheen to Rochester, New York.

The final pages of Hughes’ book cover Sheen’s rocky time in Rochester. Sheen was used to being a media “monologist,” not an administrator, and he didn’t last long as Rochester’s bishop. But he did remain active until his death in 1979, at age 84, while praying before the Blessed Sacrament.

Danusha V. Goska is the author of God through Binoculars: A Hitchhiker at a Monastery.