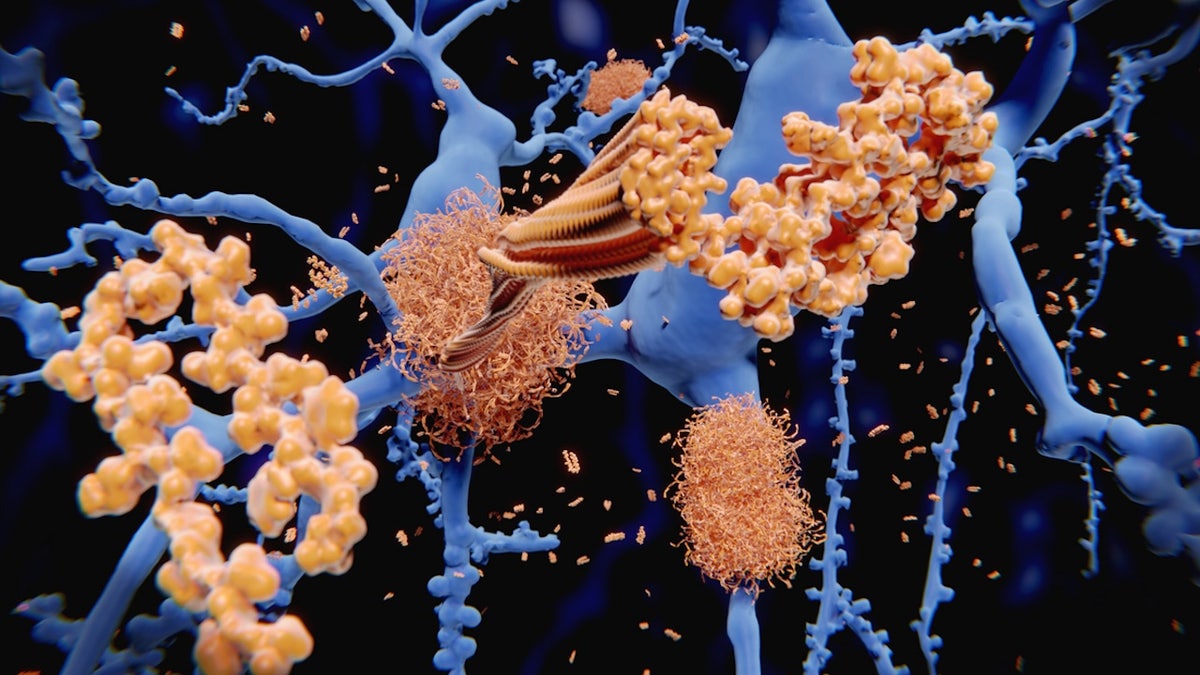

Two cancer drugs could potentially slow or even reverse the effects of Alzheimer’s disease, a new study suggests.

Researchers at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) explored how the common dementia changes gene expression (which genes are turned on or off) in certain brain cells, according to a press release from the university.

Next, they looked at which existing FDA-approved drugs might counteract, or reverse, those changes.

ALZHEIMER'S RISK COULD RISE WITH SPECIFIC SLEEP PATTERN, EXPERTS WARN

In analyzing millions of electronic medical records of adults over 65, the researchers identified two medications that appeared to reduce the likelihood of Alzheimer’s in the patients who took them.

The medications — letrozone and irinotecan — are both approved to treat cancer. Letrozole is a breast cancer medication and irinotecan treats colon and lung cancer.

When the scientists tested a combination of both medications in mice, they noted a reversal of the gene expression changes that were initiated by Alzheimer’s.

Two cancer drugs could potentially slow or even reverse the effects of Alzheimer’s disease, a new study suggests. (iStock)

They also discovered a reduction in tau protein clumps in the brain — a key marker of Alzheimer’s — and an improvement in learning and memory.

"Alzheimer’s disease comes with complex changes to the brain, which has made it tough to study and treat, but our computational tools opened up the possibility of tackling the complexity directly," said co-senior author Marina Sirota, PhD, the interim director of the UCSF Bakar Computational Health Sciences Institute and professor of pediatrics, in the press release.

EATING THESE COMMON FOODS COULD REDUCE ALZHEIMER'S RISK, EXPERTS SAY

"We’re excited that our computational approach led us to a potential combination therapy for Alzheimer’s based on existing FDA-approved medications."

The results of the study, which was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Science Foundation, were published in the journal Cell on July 21.

In analyzing millions of electronic medical records of adults over 65, the researchers identified two medications that appeared to reduce the likelihood of Alzheimer’s in the patients who took them. (iStock)

While the study’s outcome was promising, the researchers acknowledged several limitations, including the fact that the database they used to identify possible drugs was built from cancer cells, not brain cells.

They also noted that animal models were used.

"Although necessary, validation in animal models may not fully recapitulate human biology," the researchers wrote.

MEN FACE DOUBLE DEMENTIA RISK IF THEY HAVE A HIDDEN GENETIC MUTATION

There was also a noticeable gender difference in response to the medications, with male mice responding better than females.

"As a hormone modulator, letrozole might contribute to this sex difference," the team noted. "However, the analysis remains inconclusive due to the small number of male letrozole users."

The electronic medical records could also present limitations, "as data tend to be sparse and are not collected with specific research in mind."

"We’re hopeful this can be swiftly translated into a real solution for millions of patients with Alzheimer’s."

More than seven million people in the U.S. are currently living with Alzheimer’s, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

This number is expected to approach 13 million by the year 2050.

More than seven million people in the U.S. are currently living with Alzheimer’s, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. (iStock)

There are currently only two disease-modifying medications that have been FDA-approved to treat Alzheimer’s, UCSF states.

Lecanemab (Leqembi) and donanemab (Kisunla) are both monoclonal antibodies that are administered via IV infusions.

They work by reducing the build-up of amyloid plaques in the brain, but they are only effective for those with early-stage Alzheimer's and have the potential for some serious side effects, according to experts.

(Other Alzheimer’s medications help with symptoms, but don’t treat the underlying disease.)

"Alzheimer’s is likely the result of numerous alterations in many genes and proteins that, together, disrupt brain health," said co-senior study author Yadong Huang, M.D., PhD, professor of neurology and pathology at UCSF, in the release.

"This makes it very challenging for drug development — which traditionally produces one drug for a single gene or protein that drives disease."

Existing Alzheimer's drugs work by reducing the build-up of amyloid plaques in the brain, but they are only effective for those with early-stage disease. (iStock)

Looking ahead, the researchers plan to start a clinical trial to explore the combined drugs’ impact on human patients with Alzheimer’s.

"If completely independent data sources, such as single-cell expression data and clinical records, guide us to the same pathways and the same drugs, and then resolve Alzheimer’s in a genetic model, then maybe we’re onto something," Sirota said in the release.

For more Health articles, visit www.foxnews.com/health

"We’re hopeful this can be swiftly translated into a real solution for millions of patients with Alzheimer’s."