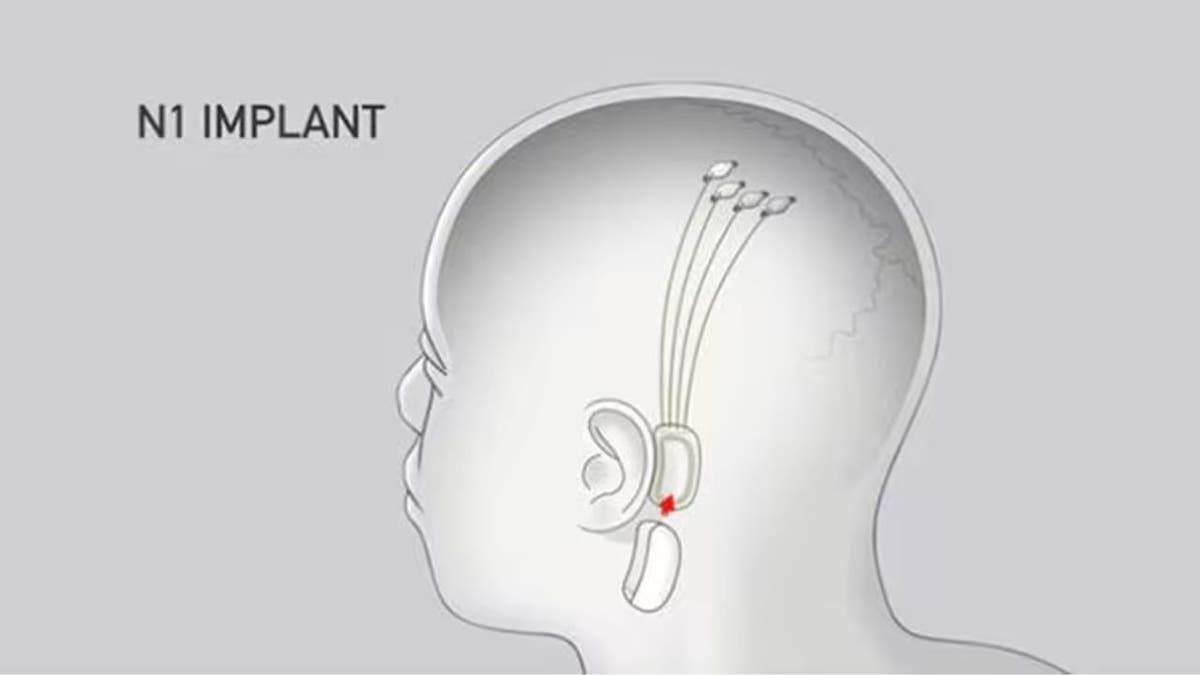

Elon Musk just announced that Neuralink — a "brain-computer interface" — had been implanted into a human brain for the first time. Patient Zero is recovering well. The technology has already undergone animal trials and has been branded as a Fitbit for the brain. Paired with your iPhone, a Neuralink could help control prosthetics, monitor brain activity in real time and boost overall cognitive capacity. It will eventually pair seamlessly with a Tesla, I’m sure.

Neuralink is only the latest in a line of novel technologies that can advance our cognitive capacities. Brain stimulation technologies have been shown to increase attention and boost creativity. The drug propranolol can modify memories. Other drugs such as Adderall and Modafinal — while used widely to treat ADHD — can be used to enhance cognition.

And a favorite of mine: optogenetics, a technique that makes neurons fire when they are exposed to light. Yes, there’s a big issue getting a flashlight into your cranium. But if we can do that, the technique presents all kinds of possibilities for cognitive enhancement. Flip a switch and watch your IQ tick up.

ANDREW YANG WARNS US 'NOT DOING ENOUGH' TO PREPARE FOR AI'S IMPACT: 'DRAMATIC CHANGES'

Cognitive enhancement does not only take our thinking up a notch — it also may help us understand moral concerns that are opaque to us now. Think of it this way: your dog has very little appreciation of morality. Sure, maybe he can understand that snacking on Thanksgiving dinner before the meal makes him a "very, very bad dog." And that letting the neighbor kids pet him even though (you’ll admit) they are kind of annoying makes him a "good dog."

Elon Musk continues to push the boundaries of science with his new Neuralink brain interface. But how will getting smarter impact future morality? (Getty Images)

But try chatting with Fido about rights or equality or the ethics of technology, and you’ll get a blank stare. Why? There are probably a few reasons. The most obvious: a human adult has a more sophisticated intellect, and so is better able to appreciate and understand morality than a dog ever could.

My point? Our cognitively enhanced future cousins may stand in relation to us as we stand in relation to our dogs. Better able to appreciate moral nuances that escape us because of our cognitive inferiority. Dumbfounded in the face of moral considerations that, at our current cognitive level, simply do not click.

But here’s the thing: none of this would actually make us more moral. The boosted IQ, the sharper memory, the greater appreciation of moral concerns. None of it. The reason is simple. Merely understanding morality does not make you morally better.

Two thousand years ago, Aristotle had a word for this: akrasia, knowing the right thing to do but lacking the will to do it. Just because our future, enhanced cousins may understand and appreciate morality better does not mean they’ll act any better. They very well may know the right thing to do — and know it better than we do — but then choose to do something else entirely. That’s Aristotle’s lesson.

More recently, the University of California, Riverside professor Eric Schwitzgebel has made the same point in a different way: through a series of studies about the moral behavior of ethicists. Presumably, ethicists know more about morality than your average Joe. They study ethics all day, after all. And yet, in study after tongue-in-cheek study, Schwitzgebel has shown professional ethicists to be not any better — or a bit worse — than the rest of us.

Professional ethicists fail to return library books more often than others, vote at a comparable rate to peers, talk at the same rate during other professors’ talks, and leave trash behind in meeting rooms at the same rate as anyone else.

Does this make ethicists moral monsters? Obviously not. But it does suggest that simply knowing more about morality won’t make you a better person. That goes for professional ethicists. It goes for our enhanced future cousins. And it goes for us, too — the unenhanced masses.

The Neuralink brain interface is the latest advancement for humans to get smarter. (Kurt "CyberGuy" Knutsson)

Really, though, we didn’t need either Aristotle or Schwitzgebel to show us this. Being smarter doesn’t make you more moral. We’ve all known the wicked smart jerk, the GPA-crushing roommate who is impossible to live with, the genius with the soured personality.

Moreover, any moral outlook that recognizes the equal dignity of all humans suggests there is something obscene about assuming that moral worth tags along with IQ. This would imply, after all, that those with a lower IQ are morally inferior. A clear violation of human dignity.

So how could we become better morally? One possibility: when it comes to enhancement technologies, skip smarts and go right for morality. Forget about enhancing IQ and instead target empathy. Or altruism. Or simply those traits associated with a sunny disposition. There’s some chance this could work.

Presumably, ethicists know more about morality than your average Joe. They study ethics all day, after all. And yet, in study after tongue-in-cheek study, Schwitzgebel has shown professional ethicists to be not any better — or a bit worse — than the rest of us.

If it did, our enhanced future cousins could be tweaked so they would not only know more than us about morality, but have a better moral compass. There’s a problem: a moral compass is only good if you want to follow where it points. And it isn’t clear how any form of enhancement could convince people to go where their enhanced compass is pointing.

The better way forward? The tried-and-true paths that are available to us right now. Study trusted moral advice and aim to live it out; engage in your local communities; learn to appreciate the beautiful and allow your vision of it inform your life; engage in religious practice; seek out solid education; serve the poor, the vulnerable, the underserved.

That’s the path to moral sainthood, and it is a path that has neither been undermined nor surpassed by Neuralink.