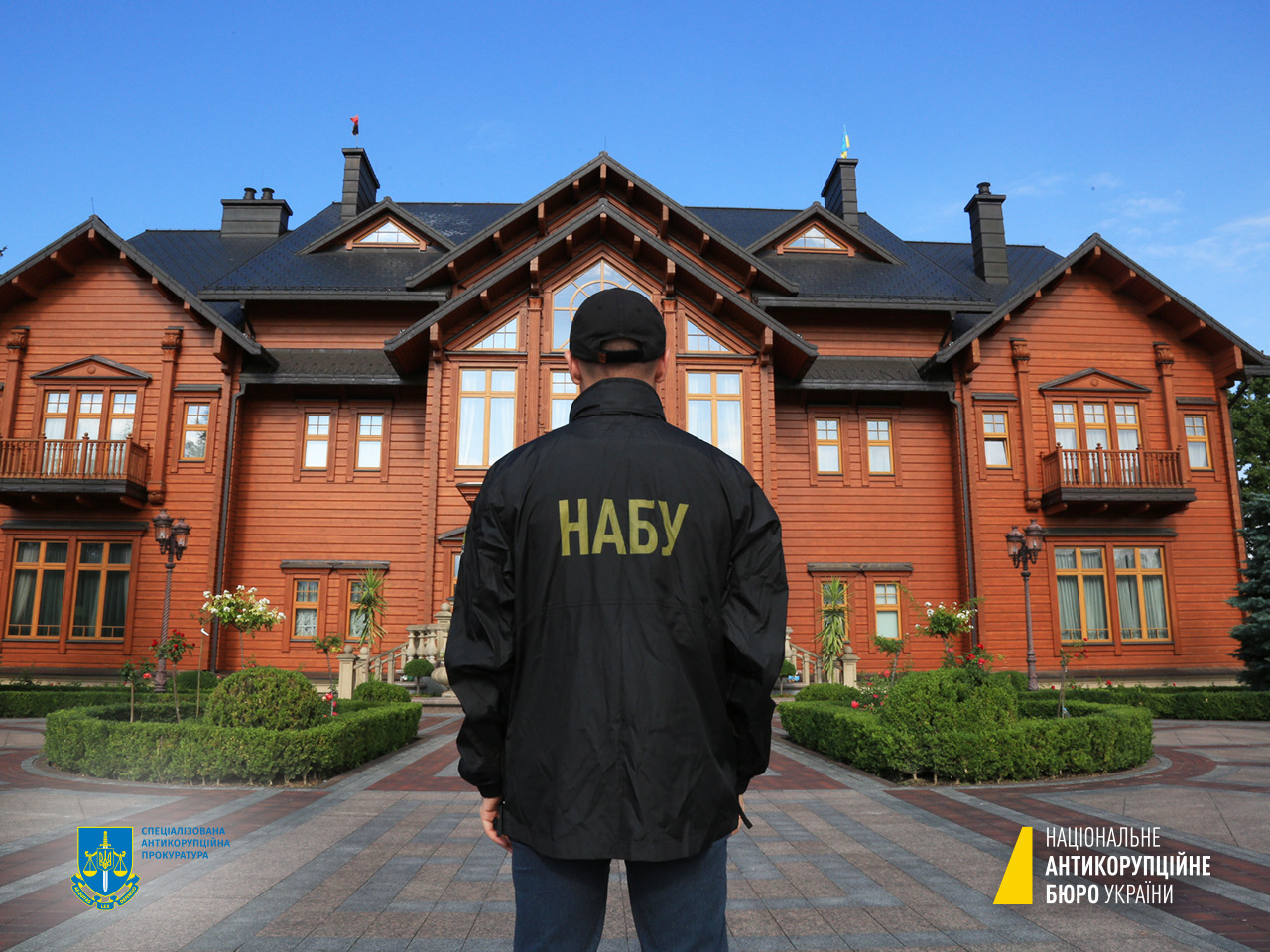

The National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU) and Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office (SAPO) delivered record results in the first half of 2025: 370 new investigations, 115 suspects charged, and 62 convictions — wartime performance that exceeded even their substantial late-2024 numbers. This week, they announced charges against a senior Defense Ministry official accused of soliciting $1.3 million in bribes to rig military housing contracts.

Yet simultaneously, a parliamentary commission has begun examining their work, a timing that raises questions about the government’s true intentions.

The question isn’t whether NABU and SAPO can function — they clearly can — but whether they can work undisturbed when the same political forces that tried to subordinate them in July remain in power, wielding the same administrative tools that could disrupt sensitive investigations.

July’s warning shot

The agencies formally regained their independence on 31 July after mass protests forced parliament to reverse controversial Law 12414. But the nine-day subordination to the Prosecutor General wasn’t an isolated misstep — it was the culmination of pressure that had been building since NABU charged former Deputy Prime Minister Oleksiy Chernyshov, a member of President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s inner circle.

What made July different wasn’t just the attempt to strip institutional independence. It was how quickly UAH 120 million ($2.9 million) appeared for Chernyshov’s bail, and how rapidly 70 raids materialized against NABU officials when the agencies refused to back down.

The message was clear: there are limits to how close anti-corruption investigations can get to the president’s political family.

The speed of that bailout also raised uncomfortable questions in Brussels, where officials watching Ukraine’s EU accession bid wondered how deep corruption networks run.

Since then, nothing fundamental has changed.

The same officials who designed Law 12414 remain in office. The same networks that mobilized Chernyshov’s bail remain intact. And crucially, parliament left three dangerous provisions that weaken the broader prosecutorial system.

The tools that remain

While NABU and SAPO regained their statutory independence, the government retained legal mechanisms that could still disrupt their work:

- No competitive selection for prosecutors during martial law: Anyone with basic legal credentials can be appointed to senior positions without open competition, potentially placing loyalists in overlapping jurisdictions.

- Dismissal through “reorganization”: Prosecutors can be fired by dissolving or restructuring their units, bypassing routine disciplinary procedures.

- Sweeping case control for the Prosecutor General: The Prosecutor General can requisition any case, halt proceedings, and give direct instructions to investigators.

The government can’t longer directly control NABU and SAPO, but it can create pressure points. Many high-profile corruption cases involve multiple jurisdictions. The Prosecutor General can, for example, influence sensitive investigations without formally touching the agencies’ autonomy by controlling appointments, reassigning personnel, or pulling case materials.

As the Agency for Legislative Initiative warned, the ability to appoint prosecutors without competition “undermines selection standards, contradicts the principle of prosecutorial independence, and creates risks for the legitimacy of personnel decisions.”

Why Western allies are watching

EU officials welcomed NABU’s and SAPO’s restored independence, but of course, they’re keenly tracking whether administrative pressure continues. Any perception that Ukraine’s anti-corruption institutions operate under political constraint could slow accession talks just as they gain momentum — exactly when Ukraine needs the perspective of a future EU membership most.

For Brussels, the July crisis and its aftermath matter beyond Ukrainian domestic politics.

The EU has made competitive selection for top prosecutorial positions a condition for Ukraine’s 2026 accession timeline. The current law doesn’t meet that requirement.

Administrative warfare

Beyond formal legal tools, the government has other ways to signal displeasure. The parliamentary commission examining NABU and SAPO, launched just weeks after their independence was restored, exemplifies this approach.

Commission chair Serhiy Vlasenko insisted the timing was coincidental, telling the news outlet Glavcom that the idea to create such a commission had been with him for a long time because, according to him, corruption had increased many times over in the last ten years.

Then there’s the case of appointing leading NABU investigator Oleksandr Tsyvinskyi to head the Bureau of Economic Security (BEB), which only materialized under external pressure tied to Western aid packages.

Earlier this month, the government finally appointed an anti-corruption investigator they had spent months trying to reject — a high-profile example of the bureaucratic obstacles that can impede institutional progress.

EU pressure remains

This puts Ukrainian civil society in a position of permanent vigilance. The Cardboard Revolution, which forced the government to retreat in July, proved that public mobilization works, but it also showed the limits of partial victories.

Citizens managed to save NABU and SAPO’s headline independence, but the technical changes that enable indirect interference remain.

Working in hostile territory

Nevertheless, NABU’s and SAPO’s continued casework proves the agencies are functional. They seem to pursue major cases without political interference. The Defense Ministry bribery investigation, which began in June, proceeded normally through the July crisis and resulted in charges this week.

But functionality isn’t the same as security. The agencies are working in what amounts to hostile territory — surrounded by political actors who view their independence as a constraint on executive power rather than a democratic achievement.

The real test will accompany the next high-profile case that touches Zelenskyy’s inner circle.

Will investigators proceed with the same determination they showed with Chernyshov? Will the Security Service launch another wave of “anti-Russian” raids against anti-corruption officials?

The war continues

NABU and SAPO proved Ukrainian civil society can force government retreats.

However, both anti-corruption agencies are still playing defense in a system where the same officials who tried to subordinate them remain in power, holding the same tools and probably the same views.

The next high-profile case touching Zelenskyy’s inner circle will show whether July was a genuine victory or a temporary tactical withdrawal.